BEHIND TCA DESIGN

STRUCTURE

Year

2003

A House on the Rock – A Palımpsest of Connectıon – ELEGMOI

For millennia, humans have built houses to protect themselves—from weather, animals, others. Yet protection is not isolation. On the contrary, architecture always marks a relationship—to its surroundings, to history, to the future. A House on the Rock, at the threshold between land and sea, between stability and change, between weight and flow, becomes a site of deep semantic layering. It is a palimpsest—in the sense Umberto Eco describes: a text made of layers that do not erase but rather generate meaning through their interplay.

The rock stands for permanence, for geology, for the immovable. The house that inscribes itself upon it must acknowledge its resistance. It cannot simply sit; it must engage, respond, adapt. It does not drill in, but rather leans, like a second skin. The first layer of this architectural text is thus the geological: the rock as carrier of memory, the original archive.

Yet beneath—or perhaps above; the order blurs—comes the water. The sea is not just backdrop; it is an active participant. It advances, retreats, reflects, floods, soothes. For centuries, it has drawn forms, laid traces—like an author writing again and again over the same sentence, altering but never erasing. The house on the rock responds by rewriting the path to the water: not as a direct descent, not as separation, but as a choreographed approach. The path becomes a litany, a repetition with variations. It opens space for interpretation, for shifts in meaning—a semantic gesture.

Thus, a house emerges that knows no final form. Different cultures, times, inhabitants continue writing upon it. They do not erase, they revise. A window becomes a door, a room becomes a threshold, a roof becomes a lookout. What remains is a structure of thought: the house as an ongoing translation of the relationship between human, rock, and water. Each new layer comments on the last, affirms or contradicts it—like in Eco’s open work, never finished, always to be read, interpreted, lived.

This house on the rock is not a solitary figure. It is a sentence in a long dialogue. An echo of earlier dwellings, a premonition of future forms. Its architecture is not a style but a posture: attentive, responsive, interpretive. In it, the site is not used, but understood. The path to the sea—once purely functional—becomes a semantic act. A new meaning emerges: connection, not conquest; resonance, not control.

In this idea lies its future: not as monument, but as manuscript. Continuously rewritten, but never erased.

———————————————————————————————————

Kayadaki Bir Ev – Bir Bağlantı Palimpsesti

İnsanlar binlerce yıldır kendilerini korumak için evler inşa ediyorlar — hava koşullarından, hayvanlardan, diğer insanlardan. Ama koruma, yalıtım demek değildir. Aksine, mimarlık her zaman bir ilişkiyi işaret eder — çevreyle, tarihle, gelecekle. Kayadaki bir ev, kara ile denizin, durağanlık ile değişimin, ağırlık ile akışkanlığın kesişiminde yer alır ve derin anlamsal katmanlardan oluşan bir mekâna dönüşür. Umberto Eco’nun tarif ettiği anlamda bir palimpsesttir bu: silinmeyen, üst üste binerek anlam üreten bir metin.

Kayalık, kalıcılığı; jeolojiyi; yerinden kıpırdamaz olanı simgeler. Ona yerleşen ev, bu direnci kabul etmek zorundadır. Basitçe oturamaz, yerleşemez — ilişki kurmalı, cevap vermeli, şekil almalıdır. Kayayı delmez; ona yaslanır, ikinci bir deri gibi. Bu mimari metnin ilk katmanı jeolojiktir: kaya, belleğin taşıyıcısı, ilk arşivdir.

Ama altında —ya da belki üstünde; bu sıradağılma— su yer alır. Deniz sadece bir arka plan değil, aktif bir aktördür. Yaklaşır, çekilir, yansıtır, taşar, yatıştırır. Yüzyıllardır biçimler çizmiş, izler bırakmıştır — aynı cümleyi tekrar tekrar yazarak değiştiren ama asla silmeyen bir yazar gibi. Kayadaki ev buna, suya giden yolu yeniden yazarak cevap verir: doğrudan bir iniş değil, bir ayrım değil; koreografik bir yaklaşım. Yol, bir ilahiye dönüşür; varyasyonlarla tekrar eden bir yapı. Anlam değişimlerine, yorumlamalara açık bir semantik jesttir bu.

Böylece nihai bir biçimi olmayan bir ev ortaya çıkar. Farklı kültürler, zamanlar, sakinler onu yazmaya devam eder. Silmezler, yeniden yazarlar. Bir pencere kapıya, bir oda eşiğe, bir çatı manzaraya dönüşür. Kalıcı olan düşünce yapısıdır: insan, kaya ve su arasındaki ilişkinin sürekli bir çevirisi olarak ev. Her yeni katman, bir öncekini yorumlar, onaylar ya da ona karşı çıkar — Eco’nun açık yapıtı gibi: tamamlanmamış, her zaman yeniden okunacak, anlaşılacak, yaşanacak.

Bu kayadaki ev, bir yalnızlık ifadesi değildir. Uzun bir diyaloğun içinde bir cümledir. Önceki barınakların yankısı, geleceğin biçimlerine dair bir önsezi. Mimarisi bir tarz değil, bir duruş: dikkatli, yanıt veren, anlamaya çalışan. Bu evde, mekân sadece kullanılmaz; okunur. Eskiden yalnızca işlevsel olan suya giden yol, burada anlamsal bir eyleme dönüşür. Yeni bir anlam ortaya çıkar: fethetmek değil bağ kurmak; denetim değil yankı.

Ve işte bu fikirdedir geleceği: bir anıt değil, bir elyazması olarak. Sürekli yeniden yazılan, ama asla silinmeyen bir yapı.

Behind every design lies an unspoken truth: architecture is not simply about creating spaces; it is about creating life. It is about offering a sanctuary for thought, for action, for the heart.

Year

2003

“A Crystal Facıng the Sea”

There is a stone house leaning toward the sea,

built upon a cliff,

its face turned south—

to the wind, to the salt, to the sun.

Once, it was the eye of the customs officers;

now, it is a family’s weekend joy,

a home of old ledgers and new dreams.

But every home needs a bathroom.

And sometimes,

stone is not enough.

Earth is not enough.

So you turn to the sky.

You build with air.

You write architecture in light.

The bathroom designed by TCA—

gently attached to the old stone house,

like a child curling beside its mother in sleep.

When the rock offered no more room,

they reached out into space.

And there,

they suspended a space

like a crystal.

Three walls and the roof made of glass blocks.

Light breaks.

Waves reflect.

The scent of soap dissolves into the sky.

And the bathroom is no longer merely a place to bathe—

it becomes

a landscape, a dream, a poem.

Here, one meets not just water,

but oneself.

Facing the sea,

stripped not only of clothes,

but of words, of cities, of form.

Behind transparent walls, unseen—

yet seeing everything—

the gaze opens to infinity.

That crystalline extension from the stone house

becomes a bridge

between the past and the future.

Once a place to monitor taxes,

now it

sets time free.

No longer stopping anyone—

only

multiplying moments.

This bathroom

is where the silence of stone

falls in love

with the transparency of glass.

And here,

like the sea,

like the sky,

we are cleansed.

—————————————————————————————

“Denize Bakan Bir Kristal”

Bir kayanın ucunda, denize doğru eğilmiş bir taş ev var.

Yüzünü güneye, rüzgâra, tuza dönmüş.

Bir zamanlar gümrükçülerin gözüydü bu ev;

artık bir ailenin hafta sonu neşesi,

eski defterlerin, yeni düşlerin evi.

Ama her evin bir banyoya ihtiyacı var.

Ve bazen, taş yetmiyor, toprak yetmiyor.

O zaman

havaya yazıyorsun mimariyi.

Rüzgârı kütüphane,

camı duvar,

ışığı tavan yapıyorsun.

TCA’nın çizdiği o banyo —

bir taş evin yanına usulca ilişmiş,

tıpkı bir çocuğun uykuda annesinin yanına sokulması gibi.

Kaya el vermeyince,

onlar göğe başvurmuşlar.

Ve oraya,

bir kristal gibi bir mekân kurmuşlar.

Dört duvarından üçü cam tuğladan.

Işık kırılıyor,

dalga yansıyor,

sabun kokusu gökyüzüne karışıyor.

Ve o banyo,

artık sadece bir yıkanma yeri değil:

bir manzara, bir düş, bir şiir oluyor.

İnsan burada suyla değil,

kendisiyle buluşuyor.

Denize karşı,

çırılçıplak kalıyor kelimelerden, şehirden, kalıplardan.

Cam duvarlar arkasında görünmeden,

ama her şeyi görerek,

sonsuzluğa açılıyor gözlerin.

O taş yapıdan uzanan kristal uzantı,

sanki geçmişle geleceğin arasında bir köprü.

Bir zamanlar vergileri denetleyen bu yer,

şimdi zamanın kendisini serbest bırakıyor.

Kimseyi durdurmuyor artık;

yalnızca

anları çoğaltıyor.

Bu banyo,

taşın suskunluğu ile

camın şeffaflığının

birbirine âşık olduğu yerdir.

Ve insan burada

gökyüzü gibi,

deniz gibi,

temizlenir.

Year

2010

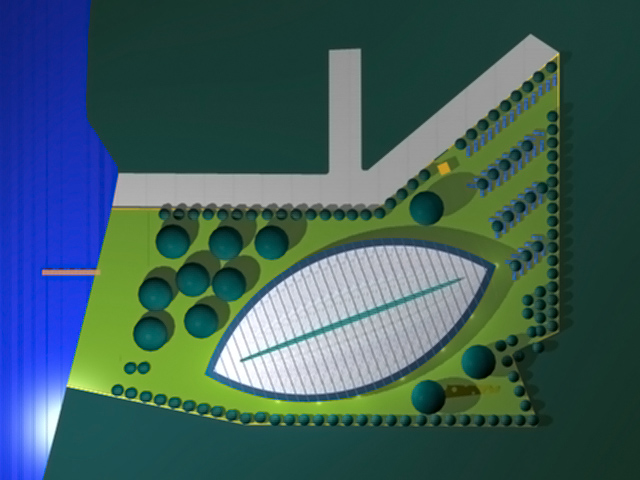

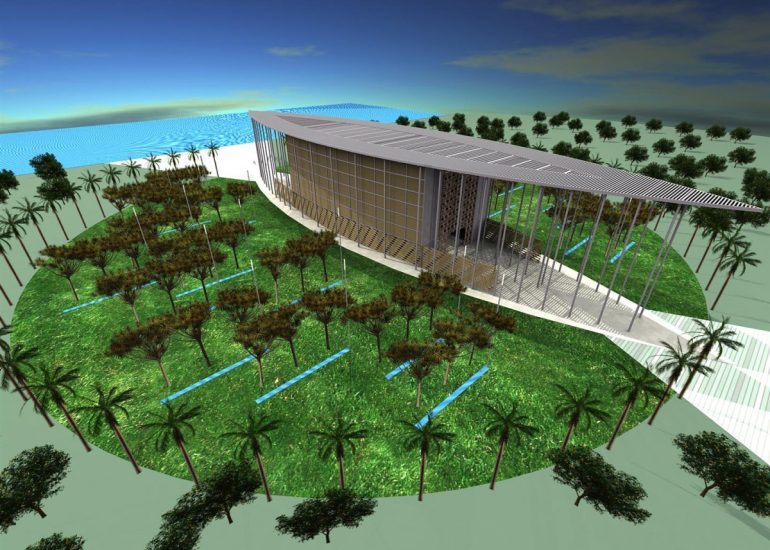

THE CAMELLIA – AN ESSAY ON SPACE, NATURE, AND MEANING

In a time when landscape itself has become the stage of humankind, the act of design is no longer merely a question of function or form – it becomes a question of meaning. Landscape architecture is not the simple arrangement of paths, grasses, or volumes. If it is to be taken seriously, it is an act of interpretation – a text to be read.

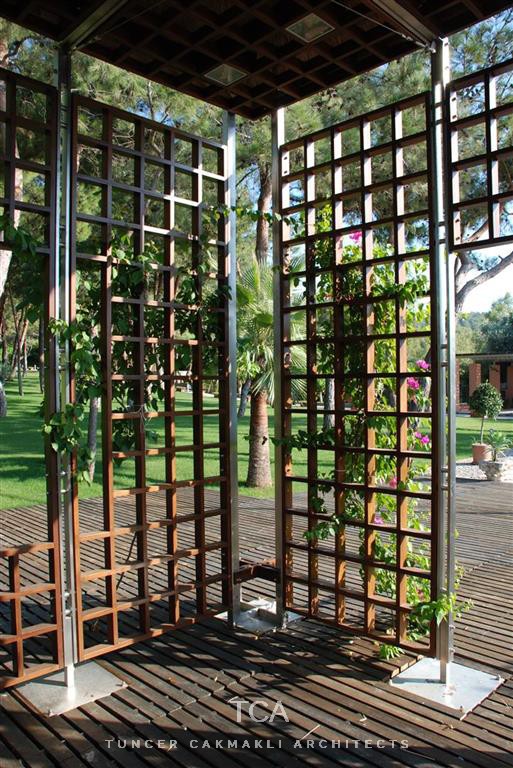

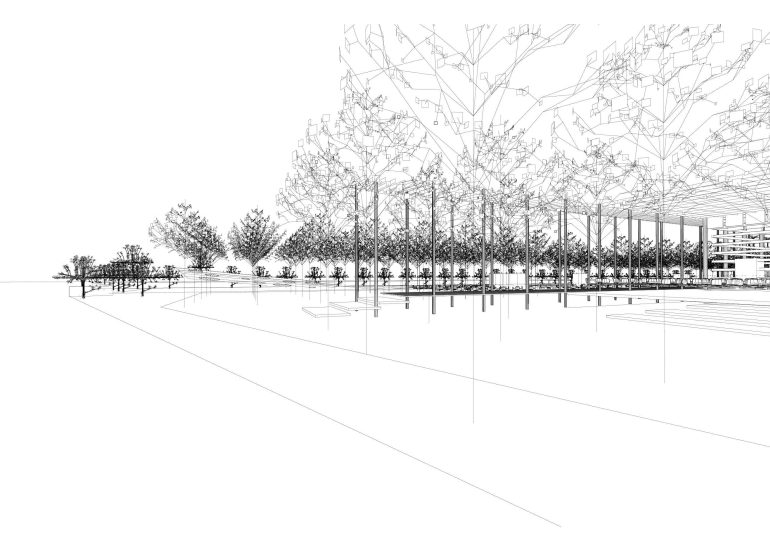

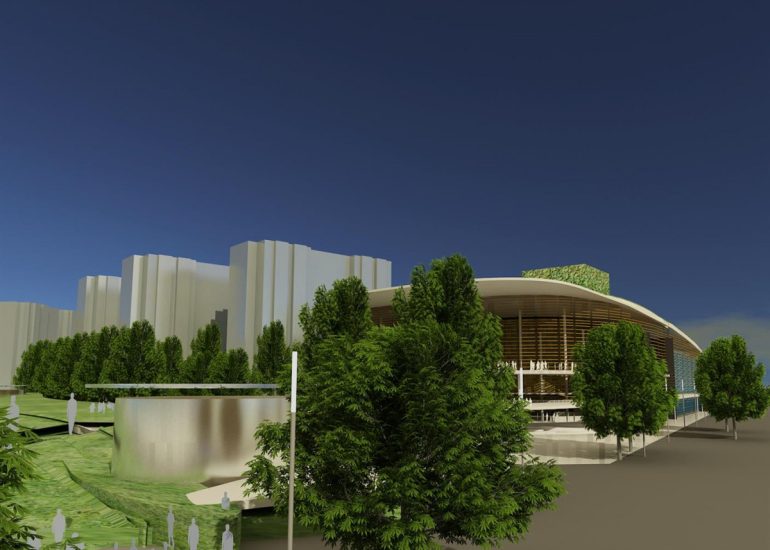

The Camellia, designed by TCA, is such a text. A sentence set into nature – not against it, but alongside it. It is not simply an object or a structure, but a sign, a semiotic fabric that gives voice to the landscape without silencing it. A gesture that does not withdraw from its surroundings, but elevates them.

What is it? A space. Open, yet sheltered. A place for pause and reflection. An in-between – between path and destination, between light and shade, between architecture and vegetation. The Camellia is not the endpoint of a walk, but its quiet climax. It does not define; it suggests. It does not close; it opens.

Formally, it is clear: geometry, transparency, materiality. Stainless steel meets wood – a combination that may appear cool at first glance, but in its union radiates warmth, durability, and dignity. The steel reflects the sky, the wood breathes with the earth. Nature is not enclosed but invited. The shade that the structure casts throughout the day is not a byproduct, but part of the design – fleeting, alive, like nature itself.

But what transforms the Camellia into a bearer of meaning? It is its attitude. The way it exists. Not as a monument, but as a possibility. It resists monumentality in favor of attentiveness. It does not impose – it accompanies. Its presence is an invitation to contemplation: of the landscape, of the light, of our relationship to the natural world.

In a world where speed has become the new normal, the Camellia insists on slowness. On observation. On pause. Perhaps even – on gratitude. For within it, an idea is made manifest that reaches beyond architecture: that design is responsibility. And that every intervention in the landscape is, ultimately, an ethical act.

Thus, the Camellia is not an object – it is an attitude. An attitude toward the world, toward nature, toward human presence. A sign within the fabric of the landscape – quiet, but clear. And for that very reason: indispensable.

————————————————————————————————————————————

Kamelya – Mekân, Doğa ve Anlam Üzerine Bir Deneme

Peyzajın artık insanlık için bir sahneye dönüştüğü bir çağda, tasarım eylemi artık yalnızca işlev ya da biçim sorunu değildir – bu, anlam sorusudur. Peyzaj tasarımı, yalnızca yolların, bitkilerin veya hacimlerin düzenlenmesi değildir. Eğer gerçekten ciddiye alınırsa, bu bir yorum eylemidir – okunmayı bekleyen bir metindir.

TCA tarafından tasarlanan Kamelya işte böyle bir metindir. Doğaya yerleştirilmiş bir cümle – doğaya karşı değil, onunla birlikte. Sadece bir nesne ya da yapı değil, bir işaret, doğaya ses veren ama onu bastırmayan bir gösterge sistemidir. Çevresinden kaçınmayan, tersine onu yücelten bir jesttir.

Peki nedir bu? Bir mekândır. Açık ama korunaklı. Dinlenme ve durup düşünme alanı. Arada bir yer – yol ile varış noktası, ışık ile gölge, mimarlık ile bitki örtüsü arasında. Kamelya, yürüyüşün sonu değil, onun sessiz doruk noktasıdır. Tanımlamaz, ima eder. Kapatmaz, açar.

Biçimsel olarak nettir: geometri, şeffaflık, maddesellik. Paslanmaz çelikle ahşap bir araya gelir – ilk bakışta serin görünen bu birleşim, özünde sıcaklık, kalıcılık ve asalet taşır. Çelik gökyüzünü yansıtır, ahşap toprağın nefesini alır. Doğa hapsedilmez, davet edilir. Yapının gün boyunca yere düşen gölgesi bir yan etki değil, tasarımın bir parçasıdır – geçici, canlı, tıpkı doğa gibi.

Peki Kamelyayı bir anlam taşıyıcısına dönüştüren nedir? Onun duruşudur. Varlık biçimi. Bir anıt değil, bir olasılık olarak durur. Anıtsallıktan çok dikkati, farkındalığı önceler. Dayatmaz, eşlik eder. Varlığı bir davettir – manzarayı, ışığı ve insanın doğayla ilişkisini düşünmeye çağırır.

Hızın yeni norm haline geldiği bir dünyada, Kamelya yavaşlığı savunur. Gözlemlemeyi, durmayı. Belki de – minnettarlığı. Çünkü onun içinde mimarlığın ötesine geçen bir fikir somutlaşır: Tasarım bir sorumluluktur. Ve peyzaja yapılan her müdahale, nihayetinde etik bir eylemdir.

Kamelya bir nesne değildir – bir tutumdur. Dünyaya, doğaya ve insana karşı bir duruş. Peyzajın dokusu içinde bir işaret – sessiz ama açık. Ve tam da bu yüzden: vazgeçilmezdir.

Year

2010

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SUN: A SEMIOTIC REFLECTION ON AN ARCHITECTURAL FILTER

From a certain point of view, the sun is a paradox. It gives life — and yet threatens to burn us. It reveals the world — and yet compels us to seek shelter. In this tension unfolds not only the history of humanity but also the history of its architecture.

The sun, that primeval deity rationalized into a celestial constant, is not only a source of energy but the very condition of visibility. Without light — no form, no space, no architecture. And yet: light alone is blind, piercing, relentless. It is shadow that gives us perception. Shadow that enables difference, depth, meaning.

It is therefore no coincidence that architecture has always sought to draw a veil between light and darkness, between exposure and protection. From the pergolas of antiquity to the delicate mashrabiya of Islamic architecture — the history of the architectural shadow is the story of a cultivated balance.

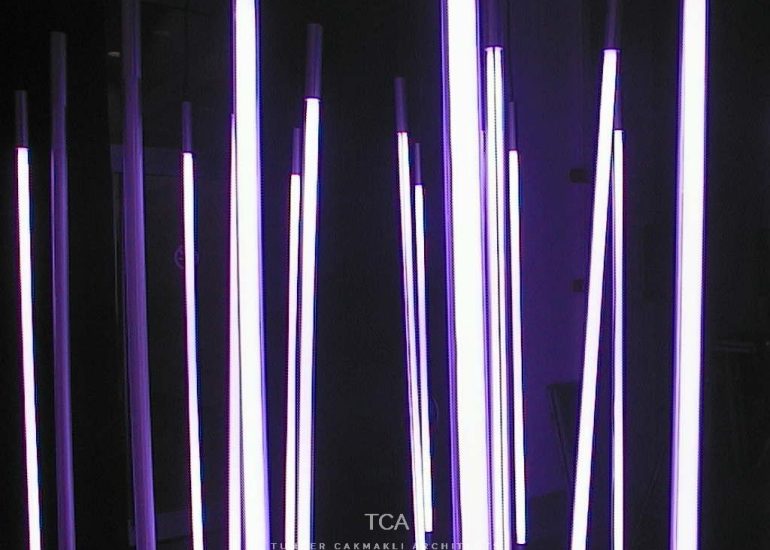

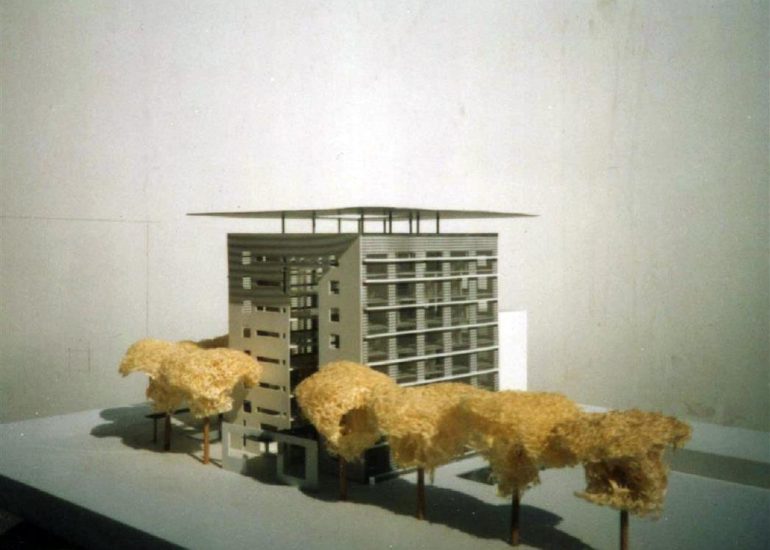

In this context, the architectural proposal by TCA is more than just a terrace. It is a choreography of light and shadow, a semiotic gesture, a piece of theatre written in segments. By day, a stage of translucent presence; by night, a silhouette dancing with the moonlight.

This design operates not with mass, but with gesture. Wooden slats — seemingly suspended, as if held aloft by invisible fingers — form a light structure that is neither fully a roof nor mere ornament. They become filters — and filters are never neutral. They determine what passes through: light, air, time.

Thus, the terrace becomes not merely a space to inhabit, but a dispositif — a device that defines thresholds, generates meaning. The varying levels of shadow are not merely functional — they are signs. They point to an idea of space that shifts, that differentiates, that responds.

And the building itself? It wears several crowns — like a mythological figure, adorned and yet marked. In this layering of function and symbolism, of lightness and monumentality, architecture becomes text. A text that demands to be read.

To live in the shadow of the sun is not to hide. It is to create a space that understands light — and filters it so that it does not blind, but reveals.

With this terrace, TCA has created a semantic space — a stage upon which life itself is performed.

Or, to put it with a smile, as Eco might have: sometimes, the shadow is the cleverest form of light.

——————————————————————————————————————————

Güneşin Gölgesinde: Mimari Bir Filtrenin Göstergebilimsel Bir Yorumu

Belli bir bakış açısından, güneş bir paradokstur. Hayat verir — ama aynı zamanda bizi yakmakla tehdit eder. Dünyayı görünür kılar — fakat bizi saklanmaya mecbur eder. Bu gerilimde yalnızca insanlığın değil, mimarlığın da tarihi yazılır.

Güneş, rasyonelleştirilmiş gökyüzünde hâlâ ilk çağların tanrısıdır. Sadece bir enerji kaynağı değil, aynı zamanda görünürlüğün ön koşuludur. Işık olmadan — biçim, mekân, mimari olmaz. Ne var ki: ışık tek başına kör edicidir, delici, yorucu. Gölge ise algının ta kendisidir. Derinliği, ayrımı ve anlamı ancak gölge verir.

Bu nedenle mimarlık tarihi, her zaman ışıkla karanlık arasında bir perde, bir denge kurma çabası olmuştur. Antik çağların pergolalarından İslam mimarisindeki ince maşrabiyelere kadar — mimari gölgenin tarihi, ölçülülüğün ve duyumsal korumanın tarihidir.

İşte bu bağlamda, TCA’nın mimari önerisi sadece bir teras değildir. Işık ve gölgenin bir koreografisidir; göstergebilimsel bir jesttir; bölümlere ayrılmış bir tiyatro eseridir. Gündüzleri yarı geçirgen bir varoluşun sahnesi, geceleri ise ay ışığıyla dans eden bir silüettir.

Bu tasarım kütleyle değil, jestle çalışır. Havada süzülüyor gibi duran ahşap paneller — sanki görünmez parmaklarla tutuluyormuş gibi — hafif bir yapı oluşturur. Ne tam bir çatı ne de yalnızca süsleme. Bunlar filtredir — ve hiçbir filtre nötr değildir. Ne geçeceğine karar verir: ışık, hava, zaman.

Bu yüzden teras yalnızca bir yaşam alanı değil, bir aygıt hâline gelir. Eşikleri tanımlar, anlamlar üretir. Gölgenin farklı katmanları yalnızca işlevsel değil, aynı zamanda işaret taşıyıcılardır. Mekânın dönüşebilen, ayrışabilen, cevap verebilen bir fikir olduğuna işaret ederler.

Peki yapı? O da birden çok taç taşır — mitolojik bir figür gibi, hem süslenmiş hem de iz bırakılmış. İşlevle sembolizmin, hafiflikle anıtsallığın üst üste binmesiyle mimarlık bir metne dönüşür. Okunmak isteyen bir metne.

Güneşin gölgesinde yaşamak saklanmak demek değildir. Işığı anlayan ve onu filtreleyerek göz kamaştırmak yerine hakikati açığa çıkaran bir mekân yaratmak demektir.

TCA bu terasla anlamlarla dolu bir sahne yaratmıştır — hayatın kendisinin sahnelendiği bir alan.

Ya da Eco’nun yapacağı gibi, hafif bir gülümsemeyle söyleyelim: bazen en akıllı ışık, gölgenin ta kendisidir.

Year

2009

UTERUS A House Lıke an Armor, a Haven Lıke a Womb Reflectıons on a Desıgn for Safety

From the outside, it might appear paradoxical at first: a building that must serve both as a place of refuge and a bearer of meaning cannot merely erect walls — it must tell stories. As I have written before, our buildings are never merely stone, concrete, or steel — they are signs. And signs that carry no meaning crumble into mere debris.

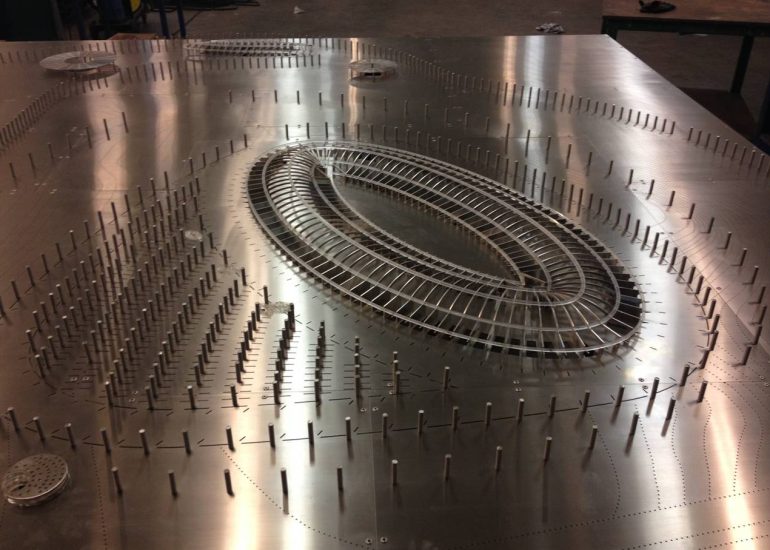

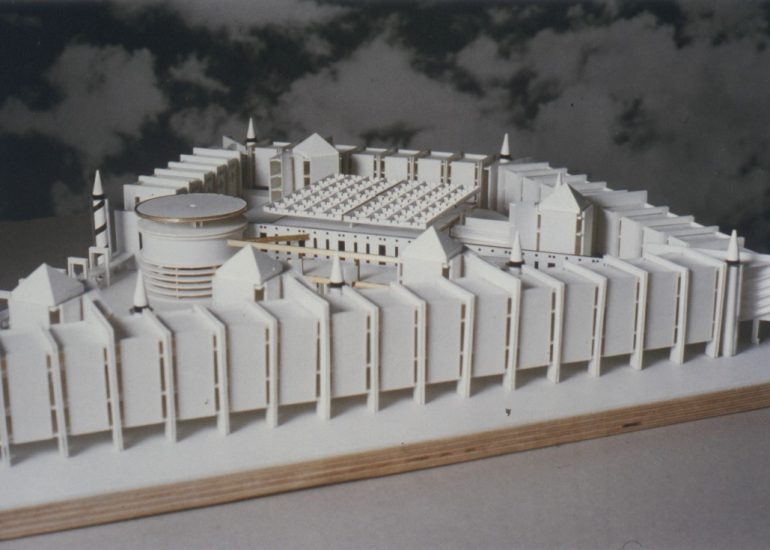

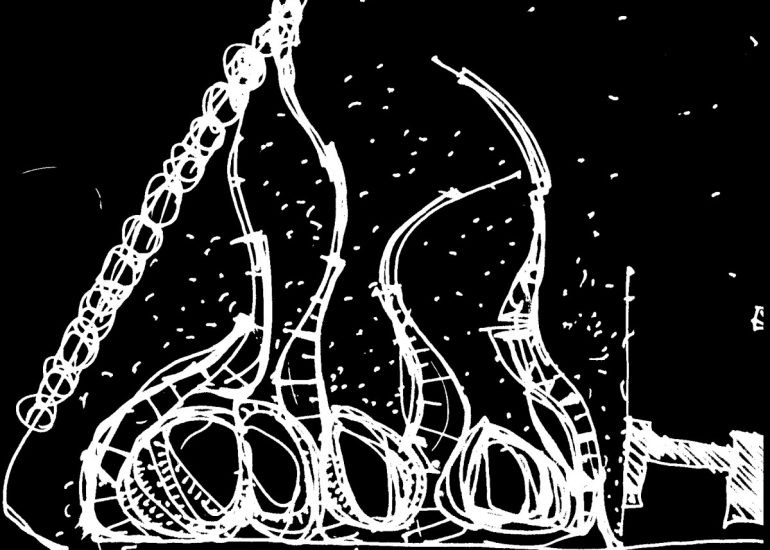

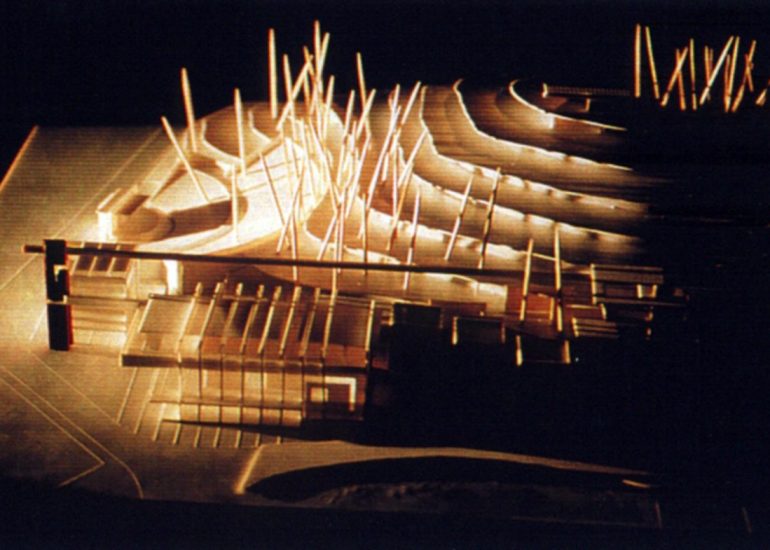

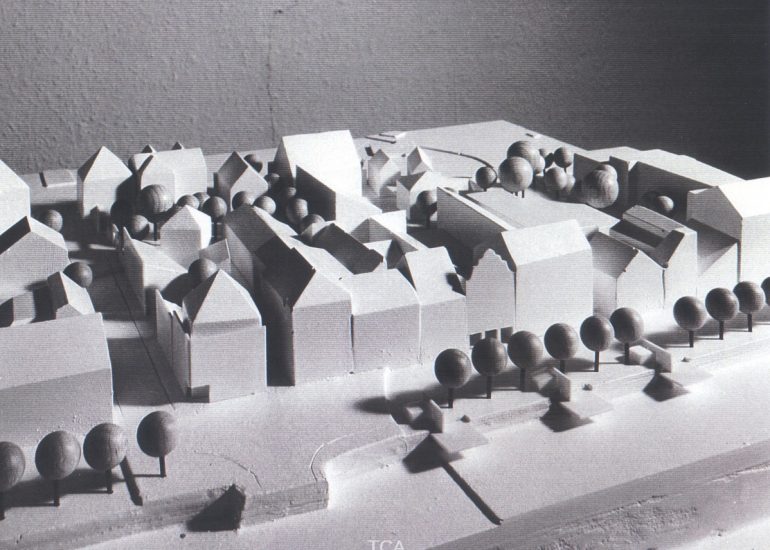

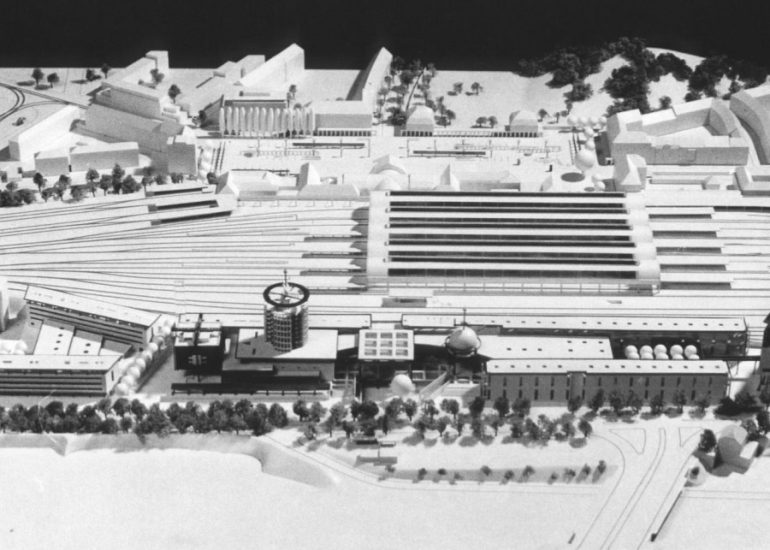

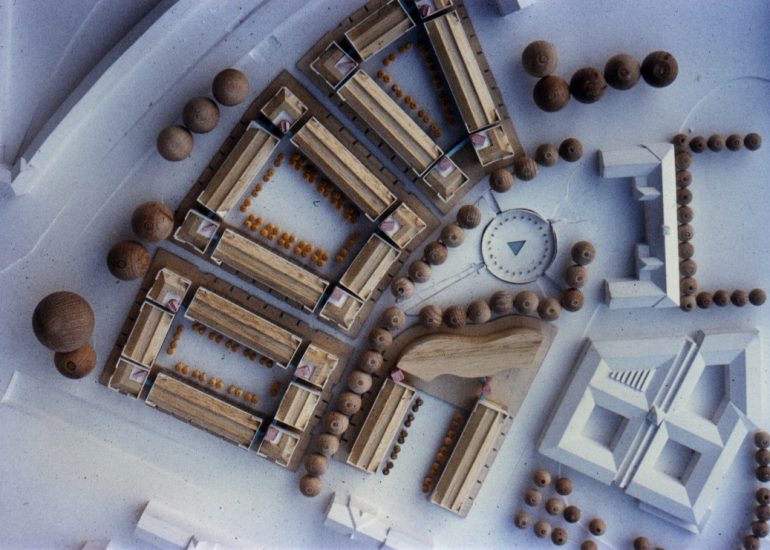

Thus, in this design, a circular structure rises — an architectural gesture that recalls the eternal validity of geometry. The circle, 360 degrees, an endless continuum: it cradles the team that rests, watches, and lives within its embrace, ready at every hour. An embrace of concrete and steel that defies the elements and grants humans shelter when the unpredictable flares outside.

Yet this is no bunker that entombs its inhabitants in darkness. Inside, a small courtyard opens — a catcher of light, an oasis. It pierces the monolithic wall; the windows become membranes between inside and out. Here, in the heart of the circular bastion, nature may flourish, the eyes may find rest. It is a gesture of reconciliation between the rigor of protection and the softness of life.

The steel framework envelops the structure like a delicate veil, softening the rigidity of the reinforced concrete. It is not a mere structural element but a semantic filter: the veil allows glimpses while shielding from overly intrusive gazes. It evokes the image of a parchment through which sunbeams seep like ink, tracing lines on the walls that shift with each passing hour — a living palimpsest of time.

For every sign, as semiotics teaches us, lives in ambivalence: it is never only what it appears to be. Thus, this building is not merely a fire station, not merely a security outpost, not merely a dwelling for a team. It is a promise. It speaks of the reliability of those who serve within — and of the necessity to create spaces that preserve the human within functional rigor.

May its walls be strong, its windows wide, its courtyard green — so that the people who inhabit it will always know why they keep watch.

———————————————————————————————————————

Bir Zırh Gibi Ev, Bir Rahim Gibi Sığınak Güvenlik İçin Bir Tasarım Üzerine Düşünceler

Dışarıdan bakıldığında bu durum ilk anda paradoksal görünebilir: Hem sığınak hem de anlam taşıyıcısı olacak bir yapı, sadece duvarlar örmekle kalamaz — hikâyeler anlatmalıdır. Daha önce de yazdığım gibi, binalarımız asla yalnızca taş, beton ya da çelik değildir — onlar birer işarettir. Ve anlam taşımayan işaretler, eninde sonunda birer yıkıntıya dönüşür.

Bu tasarımda yükselen yapı daire formundadır — geometrinin sonsuz geçerliliğini hatırlatan bir mimari jest. Çember, 360 derece, kesintisiz bir süreklilik: İçinde 24 saat nöbette, uyanık, yaşayan ekibi sarıp sarmalar. Beton ve çelikten bir kucaklama; dışarıda belirsizlik alevlenirken insanlara sığınak sunar.

Ancak bu yapı, sakinlerini karanlığa gömen bir sığınak değildir. İçeride küçük bir avlu açılır — ışığı yakalayan bir durak, bir vaha. Monolitik duvarı deler; Pencereler iç ve dış arasındaki birer zar gibi işler. Dairesel kalenin kalbinde doğa yeşerir, gözler dinlenir. Bu, korumanın katılığı ile yaşamın yumuşaklığı arasında bir uzlaşma jestidir.

Çelikten oluşan örgü, yapıyı ince bir örtü gibi sarar; betonarme yapının katılığını yumuşatır. Bu sadece bir strüktürel unsur değildir, aynı zamanda anlamsal bir filtredir: Bu örtü, içeriyi tümüyle açmaz ama fazlaca meraklı bakışlardan korur. Güneş ışınlarının mürekkep gibi süzüldüğü bir parşömeni anımsatır; duvarlara her saat değişen çizgiler çizer — zamanın yaşayan bir palimpsestidir bu.

Zira her işaret, bize göstergebilim öğretir ki, çift anlamlıdır: Asla sadece göründüğü şey değildir. Bu bina da sadece bir itfaiye merkezi, sadece bir güvenlik karakolu, sadece bir ekip konutu değildir. O bir vaattir. İçinde görev yapanların güvenilirliğini ve işlevsel katılığın içinde insan olana yer açmanın gerekliliğini anlatır.

Dilerim ki duvarları güçlü, pencereleri geniş, avlusu yeşil olsun — böylece içinde yaşayanlar yarın da neden nöbet tuttuklarını unutmasınlar.

Year

2007

“The Bathroom as a Mırror of Cıvılızatıon”

When humankind settled down, when it began to build houses, it did not begin with the roof—but with fire and water. Since the dawn of sedentary life, the need to cleanse the body has evolved from a mere survival instinct into a cultural expression. Where once the riverbank sufficed, architecture demanded a new space: the bathroom.

Yet the bathroom is more than a place for hygiene. It is a declaration of how we perceive the human body—whether as a temple, a machine, or a projection of purity, control, and identity. In the Roman thermae, the bath was not only functional but social, even sacred. Bodily care became a public ritual, akin to attending mass on Sunday.

In our post-industrial age—especially in the urban context—the bathroom has become the final refuge of the individual. A private cocoon where body, mirror image, and silence encounter one another. Still, this space remains a design challenge, one that calls for order, proportion, and that silent harmony which arises only through intelligent planning.

Thus, the architectural studio TCA, located in a 120-year-old historic building in the heart of Istanbul’s Galata district—a city within the city—faced the task of designing bathrooms that were both functional and poetic, in the tightest of spaces. In a building whose walls breathe history, not a single centimeter could be wasted. Yet each floor was equipped with a bathroom that fulfilled more than necessity—it offered experience.

With movable washbasins, showers, and toilets, clad in delicately veined Marmara marble, miniature sanctuaries of comfort were created. The walls, proportioned according to the golden ratio, transform even a brief visit into a quiet composition of light, material, and measure. It is a bathroom that cleanses not only the body but also sharpens the eye—for what design, at its best, can offer: order, dignity, and poetry in the everyday.

Just as the library is a mirror of thought, the bathroom is a mirror of the body. And when both are brought into harmonious dialogue within the smallest of spaces, perhaps that is where true architecture begins.

———————————————————————————

“Banyo: Uygarlığın Bir Aynası”

İnsan yerleşik hayata geçtiğinde, ev yapmaya çatısından başlamadı; ateşle ve suyla başladı. Bedeni temizleme ihtiyacı, yerleşikliğin başlangıcından itibaren yalnızca bir hayatta kalma güdüsü olmaktan çıkıp kültürel bir tavra dönüştü. Eskiden bir nehir kıyısı yeterli olurken, mimarlığın ortaya çıkışıyla birlikte yeni bir mekâna ihtiyaç duyuldu: banyo.

Ancak banyo yalnızca hijyenin sağlandığı bir yer değildir. İnsanın beden algısının bir ifadesidir. Bedenin bir tapınak, bir makine ya da arınmanın, kontrolün ve kimliğin bir yansıması olarak görüldüğü bir çağın aynasıdır. Antik Roma’daki termal hamamlarda banyo yalnızca işlevsel değil, aynı zamanda toplumsal, hatta kutsal bir alandı. Bedenin bakımı, neredeyse bir pazar ayini gibi kolektif bir ritüeldi.

Bugün, endüstri sonrası çağda – özellikle kentte – banyo, bireyin son sığınağı hâline gelmiştir. Aynanın, bedenin ve sessizliğin buluştuğu özel bir koza… Ama bu mekân da tasarımdan bağımsız değildir. Düzen, oran ve yalnızca zekice düşünülmüş kurgularla doğan o sessiz uyumu talep eder.

İşte bu bağlamda, TCA Mimarlık Ofisi de, İstanbul’un kalbinde, Galata’da bulunan 120 yıllık tarihi binasında; dar alanlarda hem işlevsel hem de şiirsel banyolar tasarlama görevini üstlendi. Duvarları tarih kokan bir yapıda tek bir santimetrekare bile israf edilemezdi. Yine de her kata, yalnızca bir ihtiyacı değil, aynı zamanda bir deneyimi karşılayan banyolar yerleştirildi.

Hareketli lavabolar, duş ve klozetle donatılmış, ince damar yapılı Marmara mermeriyle kaplanmış bu alanlar, konforun minyatür sığınakları hâline geldi. Altın oranla ölçülmüş duvarlar sayesinde, kısa süreli bir ziyaret bile ışık, malzeme ve ölçüden oluşan dingin bir kompozisyona dönüşüyor. Bu banyolar yalnızca bedeni arındırmakla kalmıyor; gözü de eğitiyor – çünkü tasarım en iyi hâliyle düzen, zarafet ve gündelikteki şiirselliği sunar.

Bir kütüphane nasıl düşüncenin aynasıysa, banyo da bedenin aynasıdır. Ve bu ikisi en küçük alanda bile uyumlu bir diyaloğa giriyorsa, işte orada gerçek mimarlık başlar.

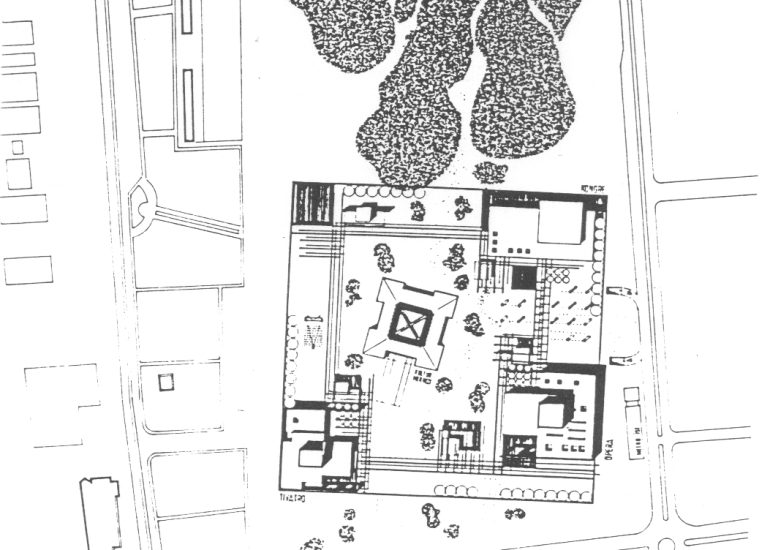

Archıtecture Is the Questıon of Spatıal Formatıon

Architecture does not begin with stone, nor with the building mass, but with an emptiness that becomes aware of itself. Space is not simply what remains between walls. Space is a setting in thought – an intellectual act that only defines itself through boundaries. Boundaries that need not be walls. A single line may suffice. A shadow. A shift in material, a subtle step in the floor, a frame of wood that closes nothing and yet contains everything.

Just as a word gains meaning only through the pause, the breath before and after it, space becomes space only through the boundary. Without boundary there is no form, without form no legibility, without legibility no meaning.

Yet here lies the paradox: every boundary in architecture is not merely separation but also connection. It is threshold, transition, membrane – it divides in order to unite. Between building mass and space, between function and meaning, between body and mind.

The architect stands within this in-between realm. One may begin with space and from it derive the building mass – or begin with the building mass and distill space from it. Both are not technical but ontological decisions. For space must be understood not only functionally, but also spiritually, symbolically, narratively. The user must not only move through it, but must be able to interpret it.

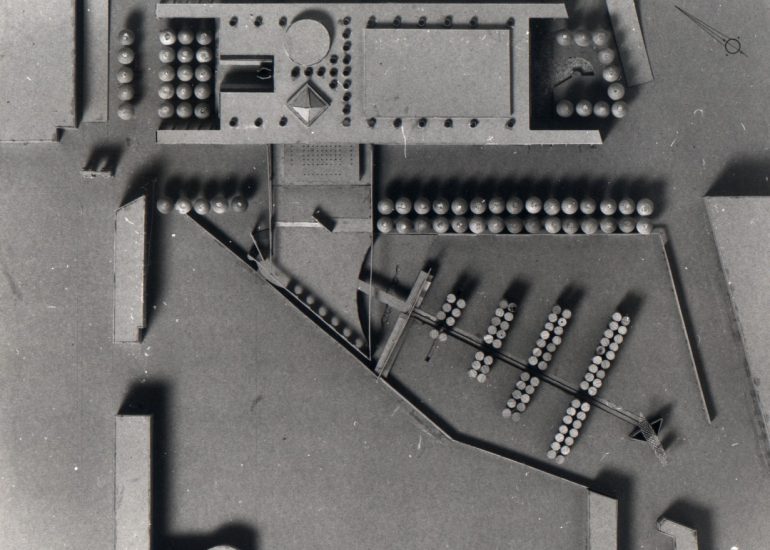

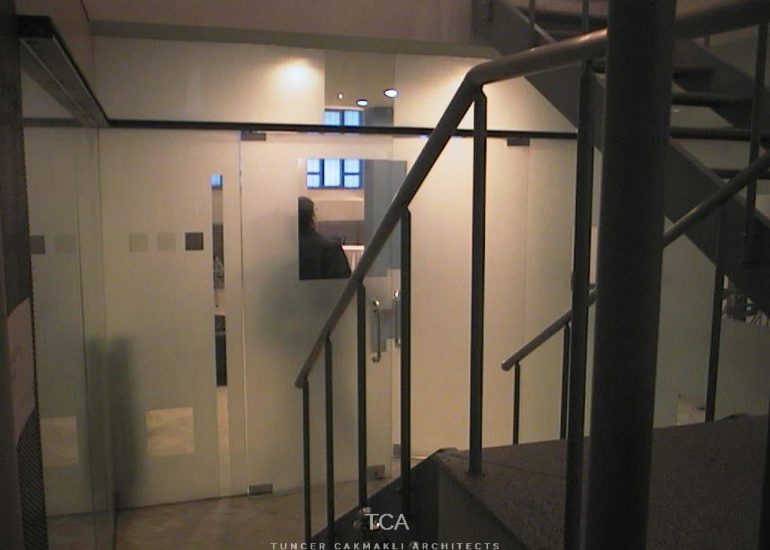

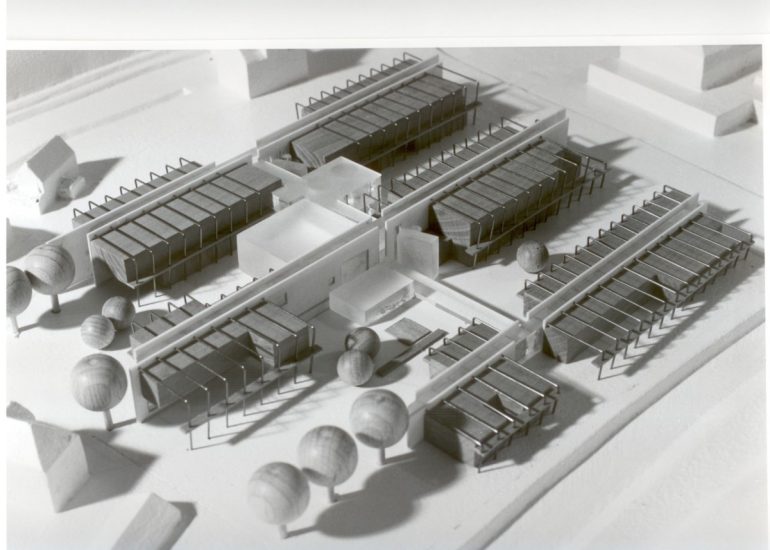

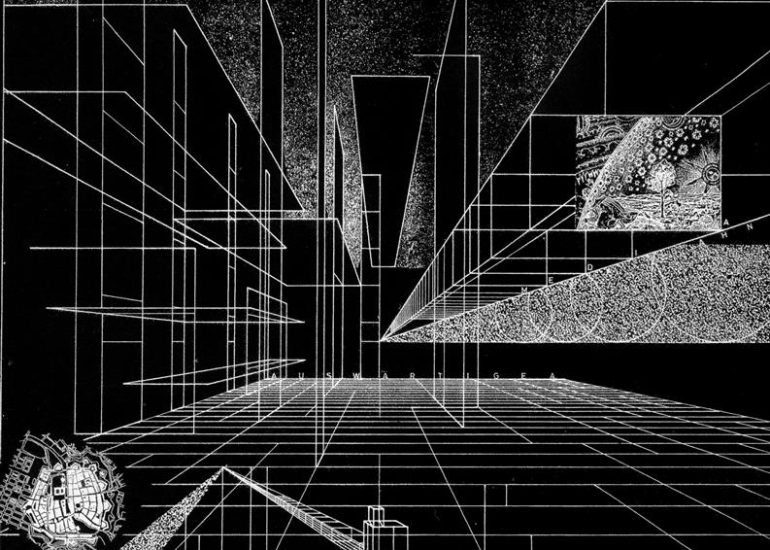

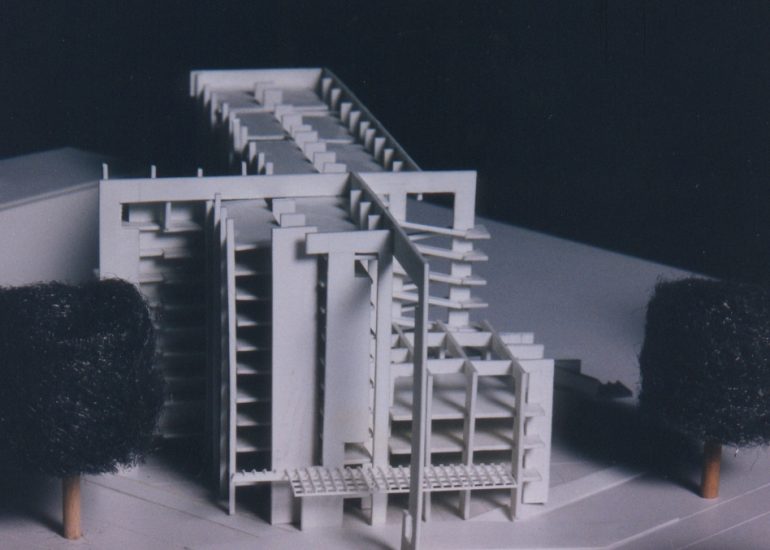

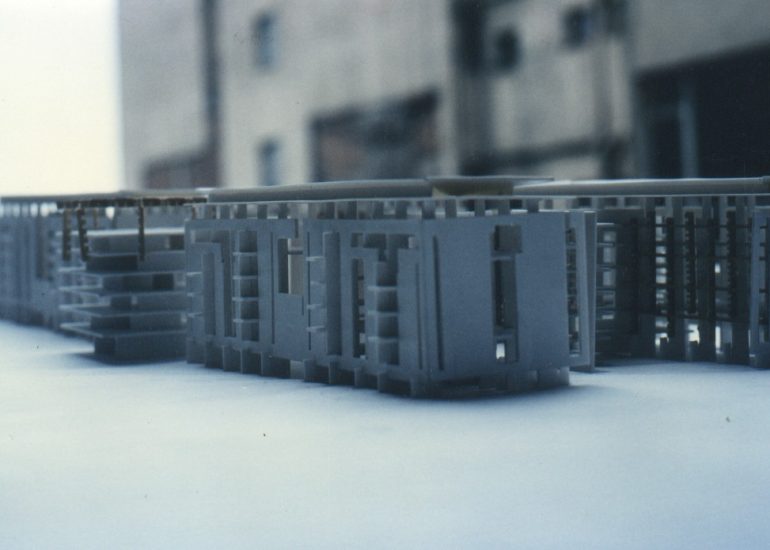

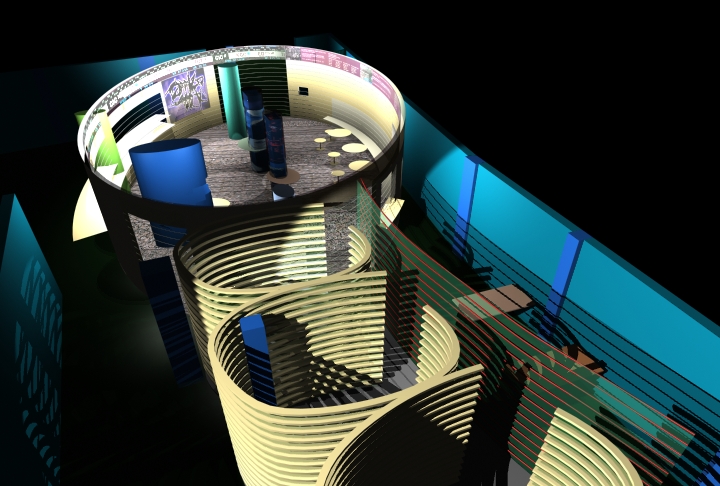

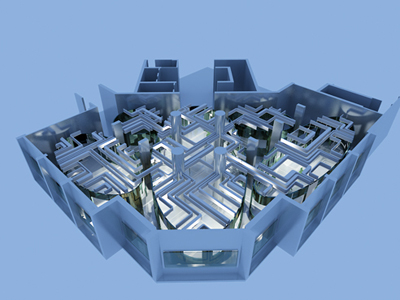

In the design of the Swiss Consular building, this logic unfolds as an infinite rhythm: interior spaces, chancery areas, framed yet never confined in a loop of wooden structures. No absolute closure. No final separation. Instead, a continuum of thresholds, lines, and vistas. The framing becomes an alphabet the visitor can read. And while reading, they experience community – a constant awareness of connection, without losing their own orientation.

Here, architecture is neither mere shell nor machine. It is sign and interpretation. It speaks equally to thought and to heartbeat. It invites the user not merely to inhabit or to work, but to locate themselves – in space, in community, in their own story.

Space, then, is the art of life. Not because it merely contains life, but because it shapes it, gives it direction, sets boundaries so that it may unfold. In this dialectic – between limit and openness, between body and mind – lies the true work of architecture.

————————————————————————————————————————

Mimarlık, Mekânın Oluşumunu Sorgulamaktır

Mimarlık ne taşla başlar ne de kütleyle; kendinin farkına varan bir boşlukla başlar. Mekân, yalnızca duvarlar arasında kalan şey değildir. Mekân, zihinde kurulan bir düzendir – ancak sınırlar aracılığıyla tanımını bulan zihinsel bir eylemdir. Bu sınırlar illa ki duvar olmak zorunda değildir. Tek bir çizgi yeterli olabilir. Bir gölge. Malzemenin değişimi, zemindeki hafif bir seviye farkı, hiçbir şeyi kapatmayan ama her şeyi çerçeveleyen bir ahşap pervaz…

Nasıl ki bir kelime ancak öncesindeki ve sonrasındaki duraklama ile, alınan nefes ile anlam kazanırsa, mekân da ancak sınırla mekân olur. Sınır olmadan form yoktur, form olmadan okunabilirlik, okunabilirlik olmadan anlam yoktur.

Ve işte burada paradoks başlar: Mimarlıkta her sınır yalnızca bir ayrım değil, aynı zamanda bir bağdır. Eşik, geçiş, zar gibidir – ayırır, ama birleştirmek için. Kütle ile mekân, işlev ile anlam, beden ile zihin arasında…

Mimar bu aralıkta durur. Önce mekândan yola çıkıp kütleyi tasarlayabilir ya da önce kütleden başlayıp mekânı ondan damıtabilir. Her ikisi de teknik değil, ontolojik bir tercihtir. Çünkü mekân yalnızca işlevsel değil, aynı zamanda ruhsal, simgesel, anlatısal olarak anlaşılmalıdır. Kullanıcı onu yalnızca geçip gitmemeli, yorumlayabilmelidir.

İsviçre Konsolosluk binasının tasarımında bu mantık sonsuz bir ritim olarak açılır: İç mekânlar, konsolosluk birimleri, ahşap çerçevelerin oluşturduğu bir döngü içinde çerçevelenir fakat asla kapatılmaz. Ne mutlak bir kapanış ne de kesin bir ayrım vardır. Onun yerine eşiklerden, çizgilerden ve görüş açıklıklarından oluşan bir süreklilik vardır. Bu çerçeveler, ziyaretçinin okuyabileceği bir alfabe hâline gelir. Ve okurken, bireysel yönünü kaybetmeden, sürekli bir bağlılık hissi yaşar.

Burada mimarlık ne yalnızca bir kabuk ne de bir makinedir. O, hem işaret hem yorumdur. Hem düşünceye hem kalp atışına seslenir. Kullanıcıyı yalnızca oturmaya ya da çalışmaya değil, kendini konumlandırmaya – mekânda, toplulukta, kendi hikâyesinde – davet eder.

Mekân, bu anlamda yaşam sanatıdır. Yalnızca hayatı barındırdığı için değil; onu şekillendirdiği, yön verdiği, sınırlar koyarak gelişmesine olanak sağladığı için. Sınır ile açıklık, beden ile zihin arasındaki bu diyalektikte, mimarlığın gerçek işi yatar.

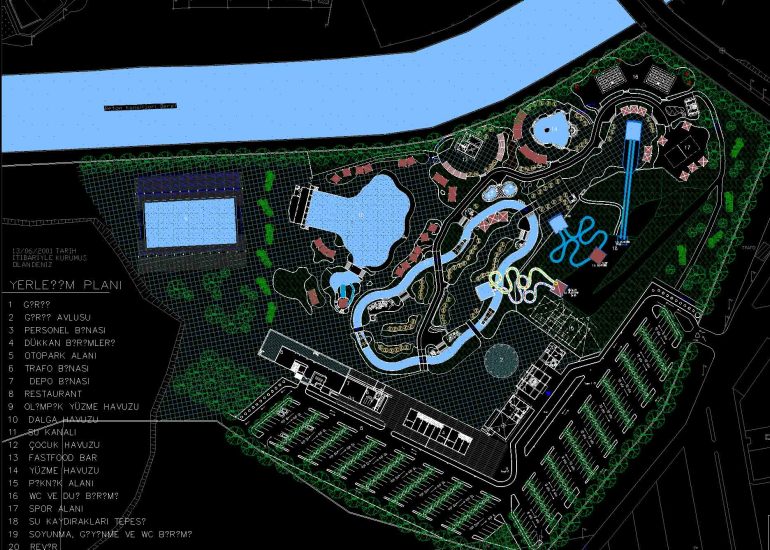

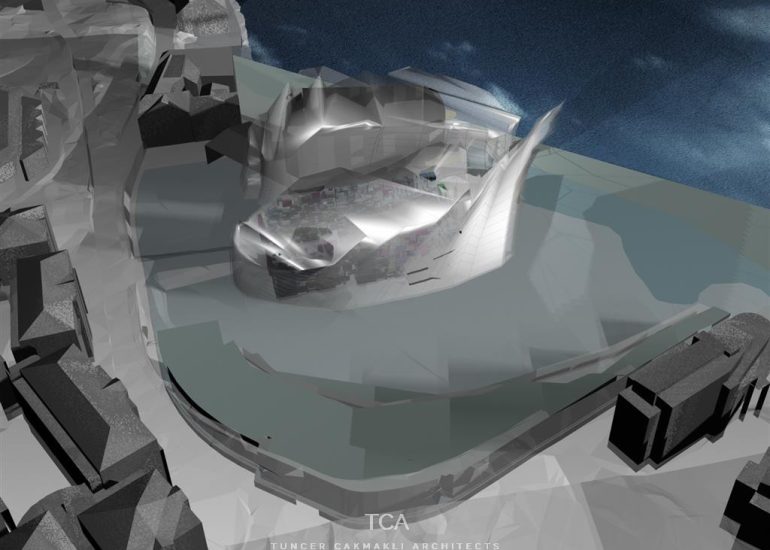

The Threshold as a SIgn

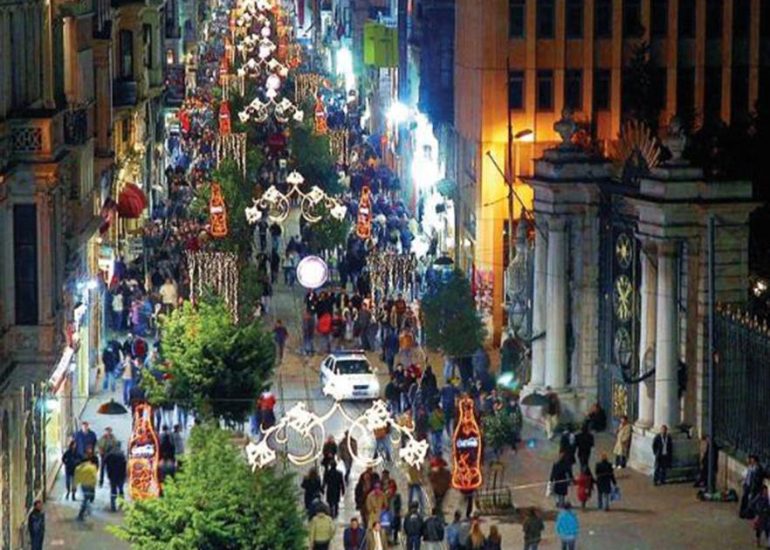

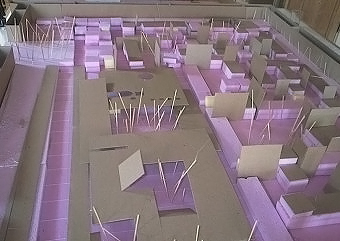

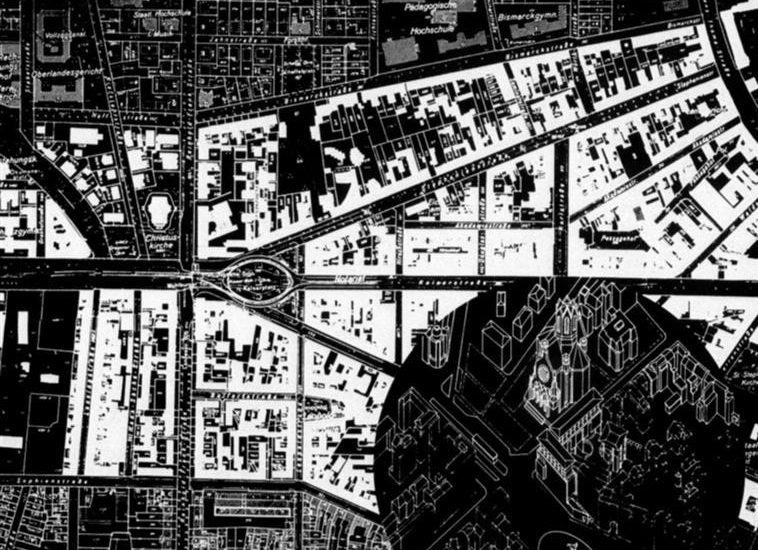

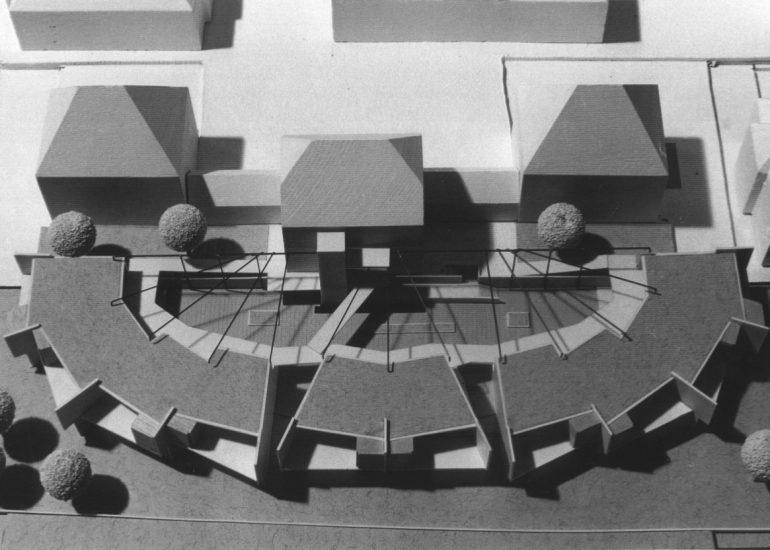

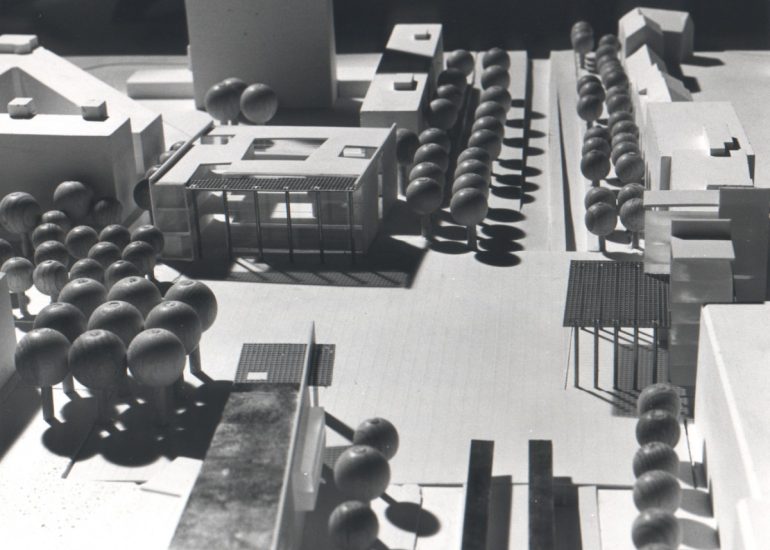

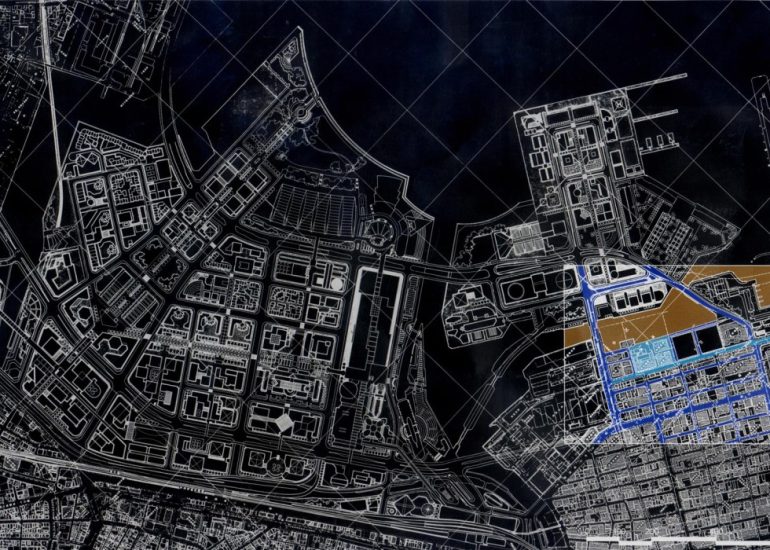

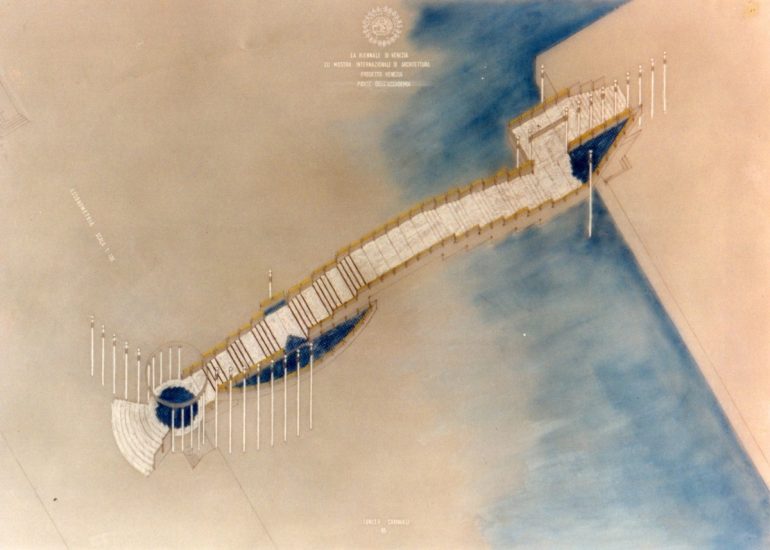

There are places that seem to be mere passages: entrances, gates, canopies, zones of control. And yet it is precisely at these thresholds that the drama of the public and the private, of inside and outside, of arrival and departure, unfolds. In Bursa, before a monumental marketplace where streams of people and goods flow each day, such a place is being reimagined.

TCA conceives of this threshold not as a mere functional detail but as an architectural metaphor. The gate is not simply a checkpoint, not merely a security barrier against disorder, but a stage: it welcomes and it bids farewell, it illuminates and becomes a sign itself.

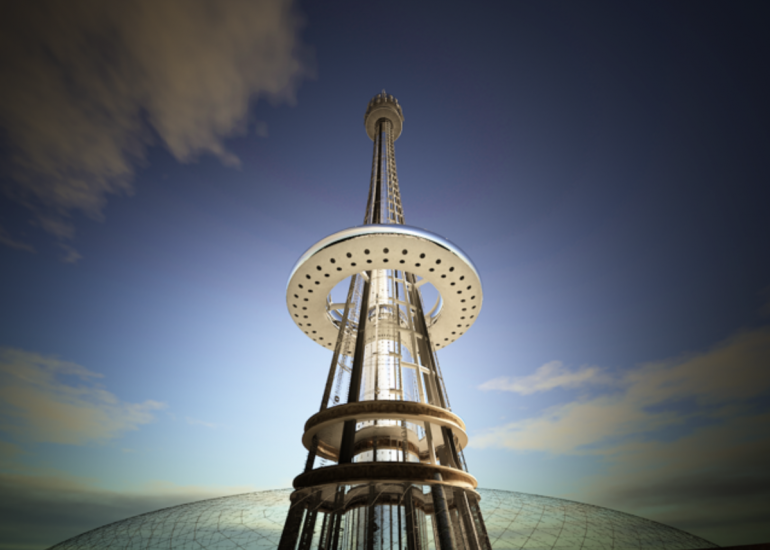

The response to this challenge is an elliptical disc, hovering, almost weightless. It rests upon slender steel columns, raised like fingers pointing toward the sky. At night, it shines — radiant like an artificial moon, a symbol of vigilance and a promise of protection. By day, it slices through the air with knife-like precision, separating inside from outside, yet never rendering that separation absolute: for every boundary is also a connection.

Thus, the canopy becomes not only a physical barrier but also an event of light and shadow. Whoever enters feels the dignity of the space; whoever departs experiences the ritual of farewell. The invisible — surveillance, order, security — merges with the visible — form, materiality, radiance — to create an architecture of attention.

This floating ellipse is more than a roof. It is a sign in the urban memory: a monument to coming and going, a threshold that not only protects but interprets. It declares to all who pass beneath it: Here begins a space of meaning.

———————————————————

Eşik Bir İşaret Olarak

Bazı mekânlar yalnızca geçiş noktaları gibi görünür: girişler, kapılar, saçaklar, kontrol alanları. Oysa tam da bu eşiklerde kamusal ile özelin, iç ile dışın, geliş ile gidişin dramı yaşanır. Bursa’da, her gün insan ve mal akışının yoğun olduğu anıtsal bir çarşının önünde, işte böyle bir mekân yeniden düşünülmektedir.

TCA bu eşiği sıradan bir işlevsel detay olarak değil, bir mimari metafor olarak ele alır. Kapı sadece bir kontrol noktası, düzensizliğe karşı bir güvenlik bariyeri değil, aynı zamanda bir sahnedir: karşılama ve uğurlama yapar, aydınlatır ve bizzat kendisi bir işarete dönüşür.

Bu ihtiyaca verilen cevap, neredeyse ağırlıksız bir şekilde havada süzülen eliptik bir diskten oluşur. Gökyüzüne uzanan parmaklar gibi yükselen ince çelik kolonlar üzerinde durur. Gece olduğunda ışıldar — yapay bir ay gibi, gözetlemenin sembolü ve korunmanın vaadi olarak. Gündüz ise, keskin bir bıçak gibi havayı yarar; iç ile dışı ayırır, ama bu ayrımı asla mutlak kılmaz: çünkü her sınır aynı zamanda bir bağdır.

Böylece bu saçak sadece fiziksel bir engel değil, aynı zamanda bir ışık ve gölge olayı haline gelir. İçeri giren mekânın yüceliğini hisseder, çıkan ise bir vedalaşma ritüelini yaşar. Görünmez olan — gözetim, düzen, güvenlik — görünür olanla — form, maddesellik, ışıltı — birleşerek bir dikkat mimarisine dönüşür.

Bu süzülen elips yalnızca bir çatı değildir. O, kentsel bellekte bir işarettir: geliş ve gidişe adanmış bir anıt, sadece korumakla kalmayan, aynı zamanda anlam veren bir eşik. Altından geçen herkese şunu ilan eder: Burada anlamlı bir mekân başlıyor.

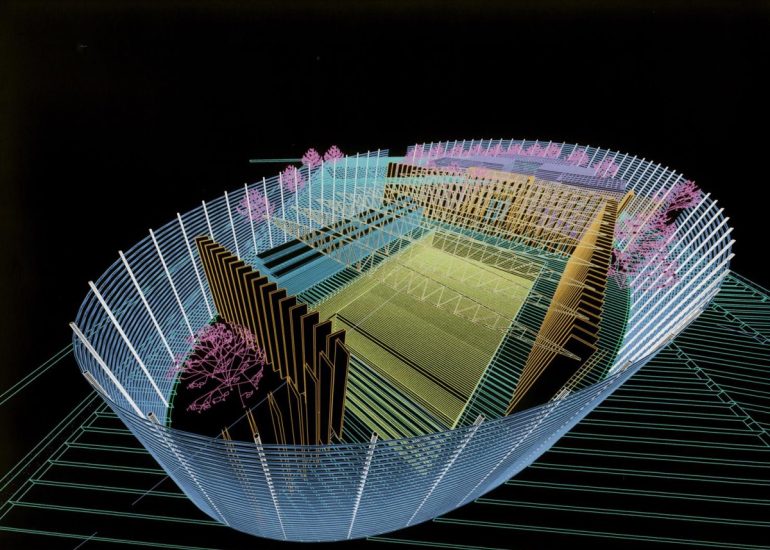

The Paradox of Structures

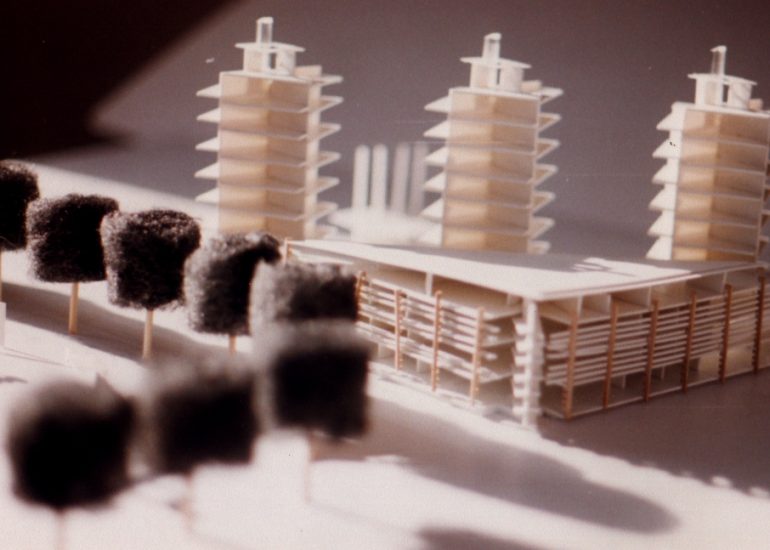

One could say that a sports hall is not simply a space where bodies move, but a space where forces take shape. What we are dealing with here is not merely a building, but a dialogue between two structures that must never intersect and yet are bound to carry a common load. A paradoxical alliance, almost like two languages that do not overlap, yet compose a single poem.

The first structure—the backbone of the hall—carries, as tradition dictates, the vertical load. It behaves like a serious scholastic, quoting gravity in his treatises to bind it into calm order. But suspended above this solemn system hangs a second order: the network of sporting equipment. This network is not stable in the classical sense. It demands not only weight, but also oscillation, sway, horizontal deviation, the sudden impulse of a jump, a fall, a twist.

Architecture is compelled to embrace both logics: the static calm of the hall and the dynamic unrest of the equipment. It is as if two opposing philosophies must be reconciled—Aristotle, who orders being, and Heraclitus, who acknowledges the flux of things. And yet, the hall insists that both be true at once.

Detailing—where iron bends, where a bolt tightens, where a suspension absorbs shock—is no mere technical gesture. It becomes the hermeneutics of forces. Every joint is a footnote in the grand commentary of statics. Every connection point is a metaphor, reminding us that architecture is not only walls and roofs, but the translation of invisible energies into a legible form.

Thus, the sports hall becomes a palimpsest of forces: the hall’s structure writes the great, calm narrative of gravity; the structure of the equipment adds the lively, trembling marginalia. Between the two arises that tension which constitutes the essence of architecture: the union of the irreconcilable, the balance of opposites, the design that emerges from the load itself.

And when the visitor, unknowingly, enters the space, he feels harmony, not conflict. He sees lines, planes, heights. Yet behind this vision lies a silent dialectic: an architecture that gives space not only to bodies, but elevates forces themselves into form.

—————————————————————

Taşıyıcıların Paradoksu

Denebilir ki, bir spor salonu yalnızca bedenlerin hareket ettiği bir mekân değildir; aynı zamanda kuvvetlerin cisimleştiği bir mekândır. Burada söz konusu olan şey, sıradan bir yapı değil, birbirine dokunmaması gereken ama ortak bir yükü taşımak zorunda kalan iki yapının diyaloğudur. Bu, neredeyse birbirine karışmadan tek bir şiir kuran iki dilin oluşturduğu paradoksal bir birlikteliktir.

İlk yapı—salonun omurgası—geleneğin gerektirdiği gibi dikey yükü taşır. O, sanki yerçekimini metinlerinde alıntılayarak düzenli bir sükûna bağlayan ciddi bir skolastik gibidir. Ama bu ağırbaşlı sistemin üzerinde, havada asılı duran ikinci bir düzen vardır: spor aletlerinin ağı. Bu ağ, klasik anlamda sabit değildir. Sadece ağırlığı değil, sallanmayı, titreşimi, yatay sapmayı, sıçrama, düşme veya dönüşten doğan ani ivmeyi de talep eder.

Mimarlık, her iki mantığı da kabul etmeye mecburdur: salonun statik huzurunu ve aletlerin dinamik huzursuzluğunu. Sanki iki karşıt felsefe bir araya getirilmek zorundaymış gibi—varlığı düzenleyen Aristoteles ile şeylerin akışını kabul eden Herakleitos. Ve yine de, salon her ikisinin aynı anda doğru olmasını ister.

Detaylandırma—demirin büküldüğü, civatanın sıkıldığı, askının darbeyi emdiği yerde—yalnızca teknik bir edim değildir. O, kuvvetlerin hermeneutiğine dönüşür. Her eklem, statiğin büyük yorumunda bir dipnottur. Her bağlantı noktası, bize mimarlığın sadece duvarlar ve çatılar olmadığını, görünmez enerjilerin okunabilir bir forma çevrildiğini hatırlatan bir metafordur.

Böylece spor salonu, kuvvetlerin bir palimpsestine dönüşür: salonun taşıyıcı sistemi, yerçekiminin büyük ve sakin anlatısını yazar; aletlerin taşıyıcı sistemi, canlı ve titreşen bir kenar notu ekler. İkisinin arasında, mimarinin özünü oluşturan o gerilim doğar: uzlaşmaz olanın birleşmesi, zıtların dengesi, yükün içinden şekillenen tasarım.

Ve ziyaretçi, farkında olmadan mekâna girdiğinde, sorunu değil uyumu hisseder. Çizgileri, yüzeyleri, yükseklikleri görür. Ama bu görüntünün ardında sessiz bir diyalektik gizlidir: yalnızca bedenlere değil, kuvvetlerin kendisine de biçim veren bir mimarlık.