Law Offices for Earthquake Victims

OFFICE

AREA

- 1200 m²

YEAR

1999

The Order of the Temporary: An Architecture of Transition

A Response to Crisis, Written in Wood

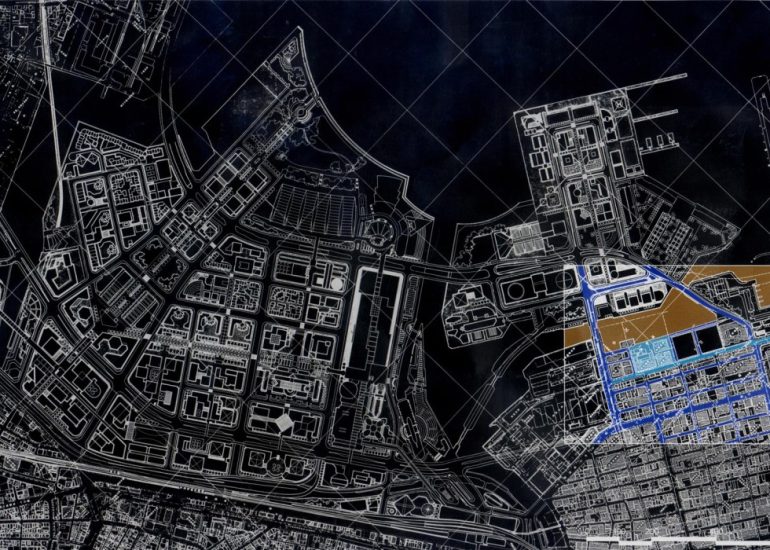

When the earth moves, it is not only the foundations of cities that tremble, but also the invisible structure of meaning we call civilization. Adapazarı, 1999 – a rupture in time, a seismic trace of loss, but also of a profound need for dignity amidst collapse. In that moment, the Bars of Athens and Istanbul did not respond with a legal memorandum or a bureaucratic protocol. They responded with a gesture – an architectural one.

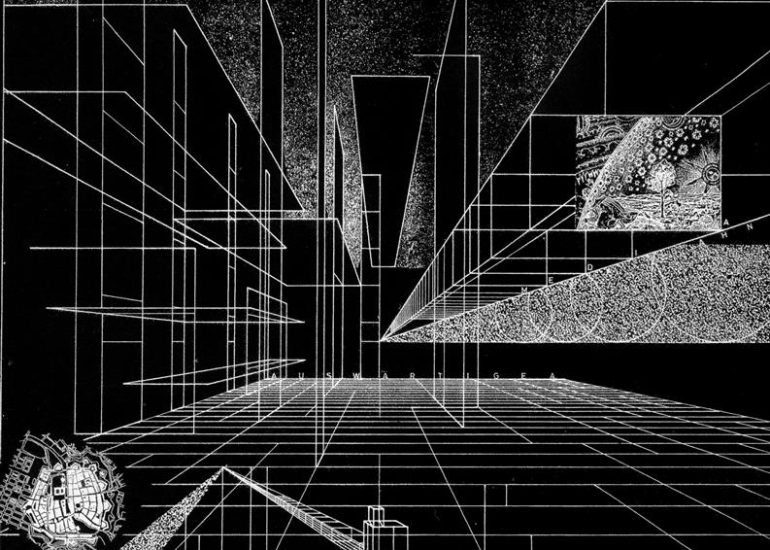

TCA was summoned – not merely as a provider of physical structures, but as an interpreter of a collective urgency. What emerged was more than a series of temporary law offices: it was an architectural palimpsest, written on the fractured ground of a devastated city.

⸻

1. The Module as Metaphor

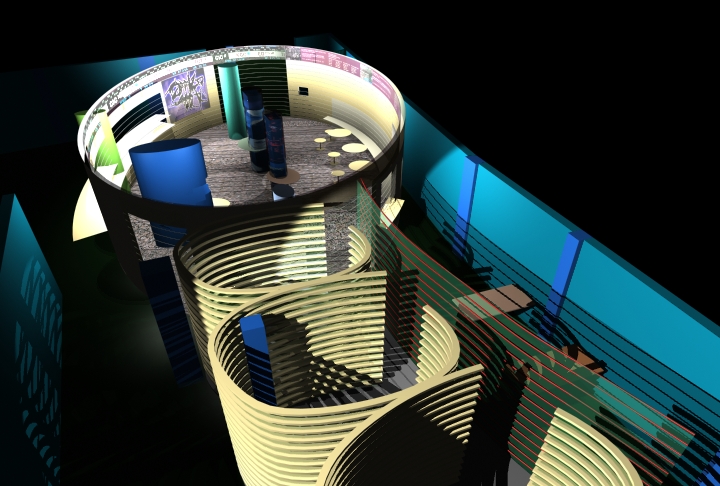

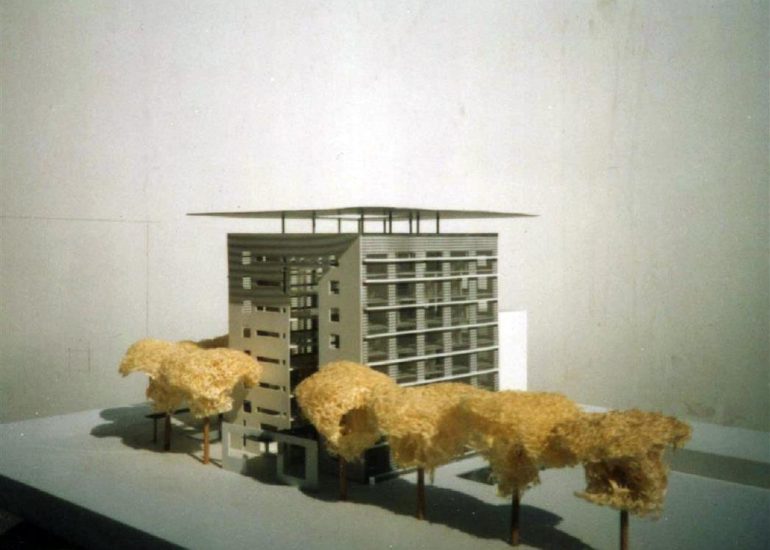

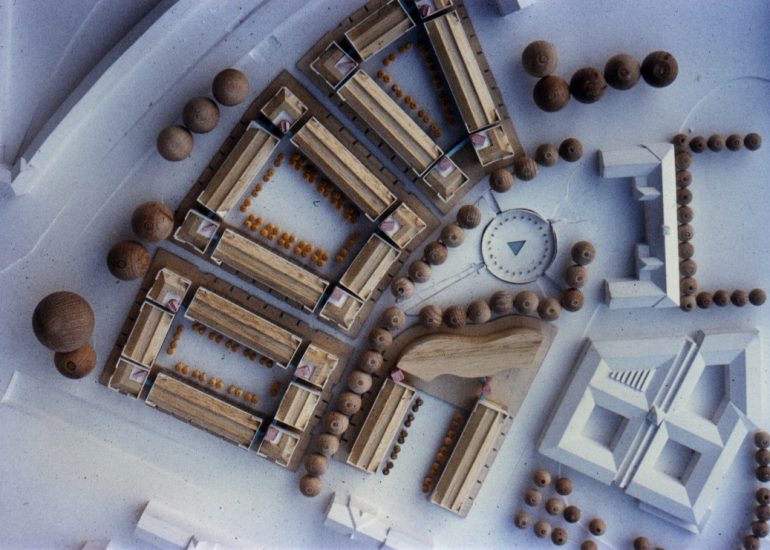

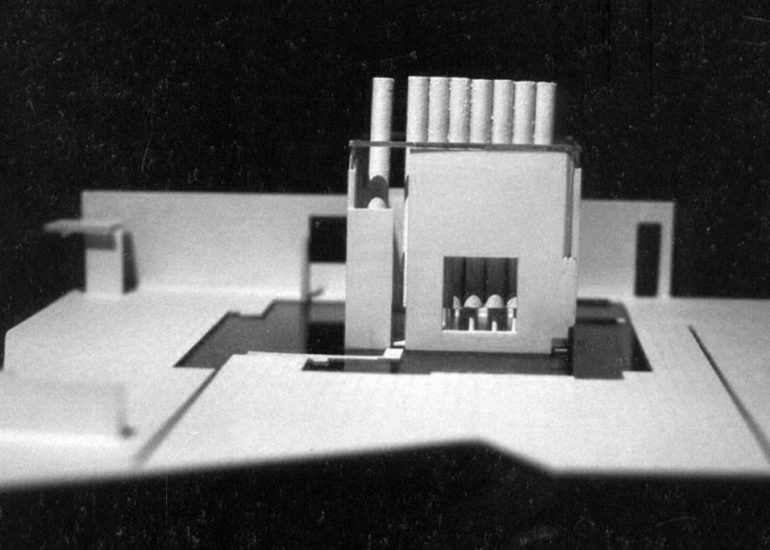

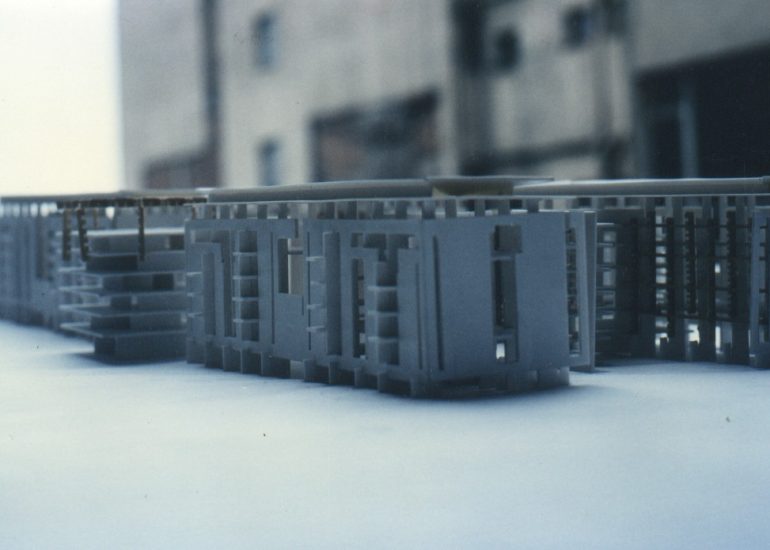

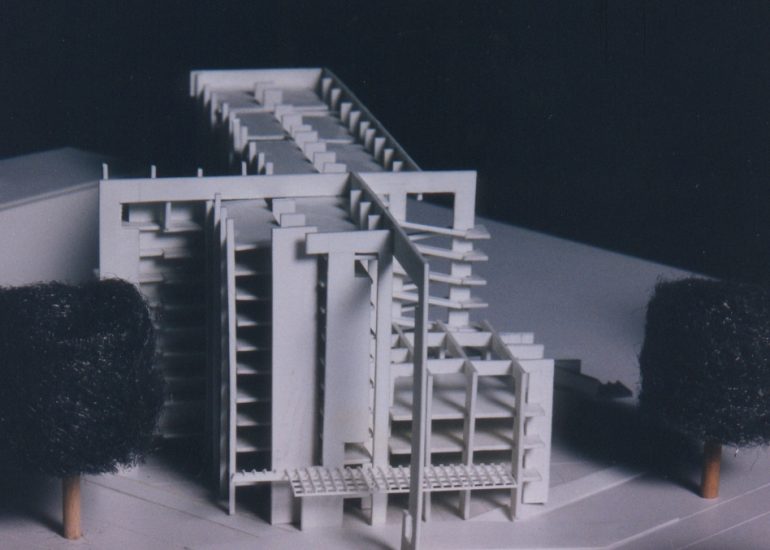

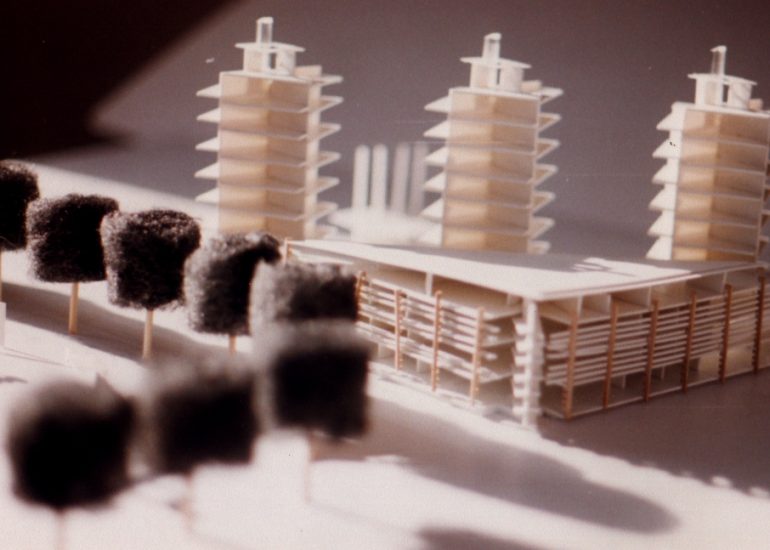

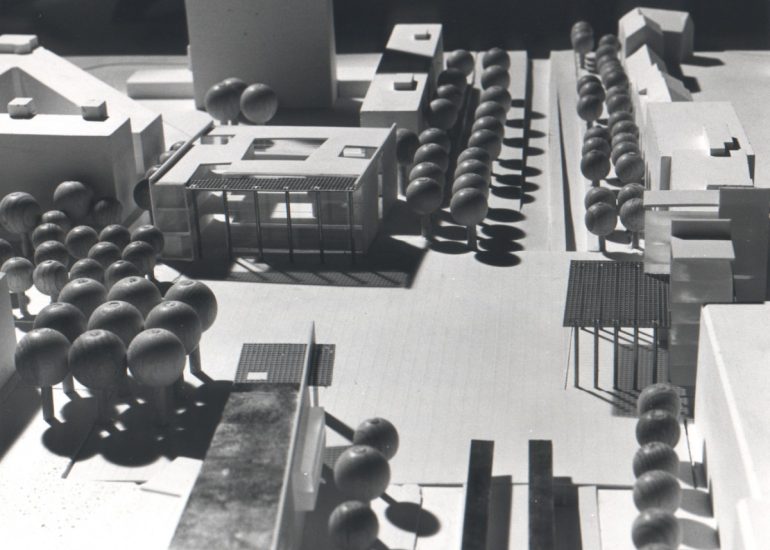

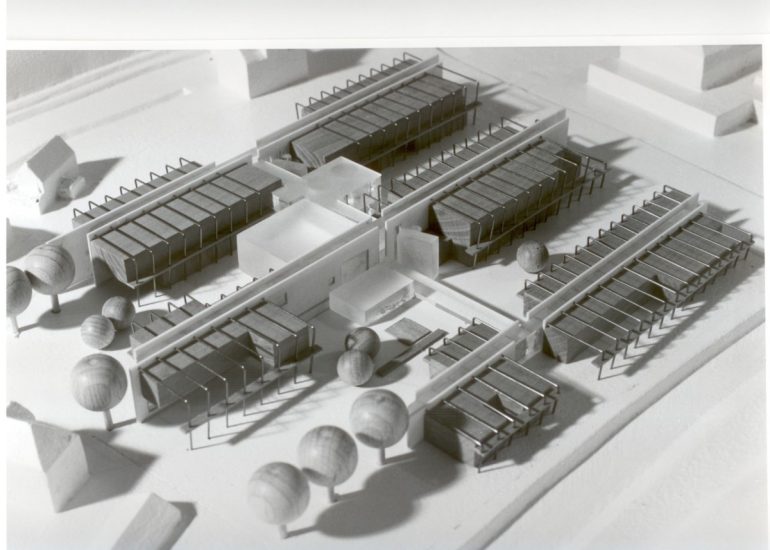

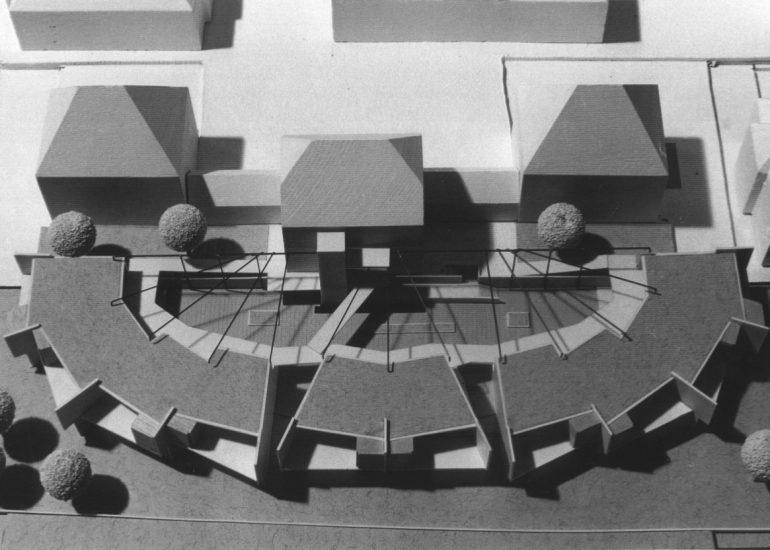

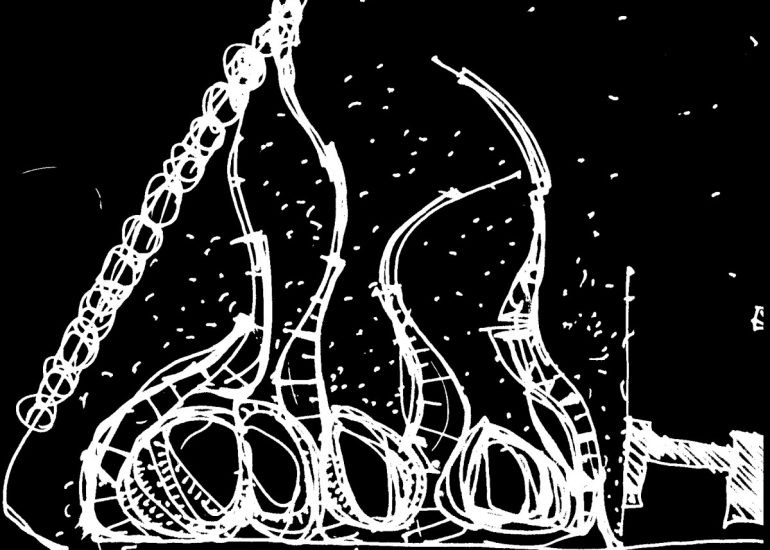

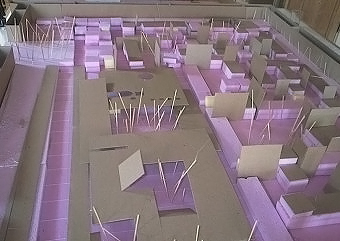

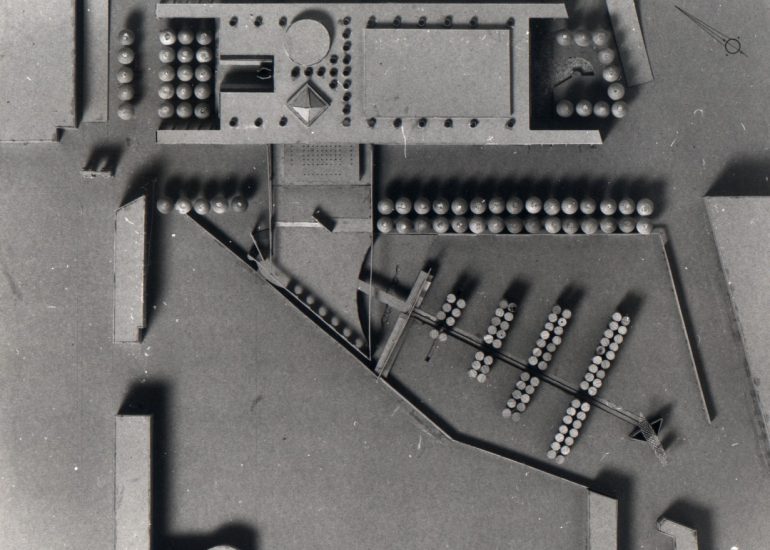

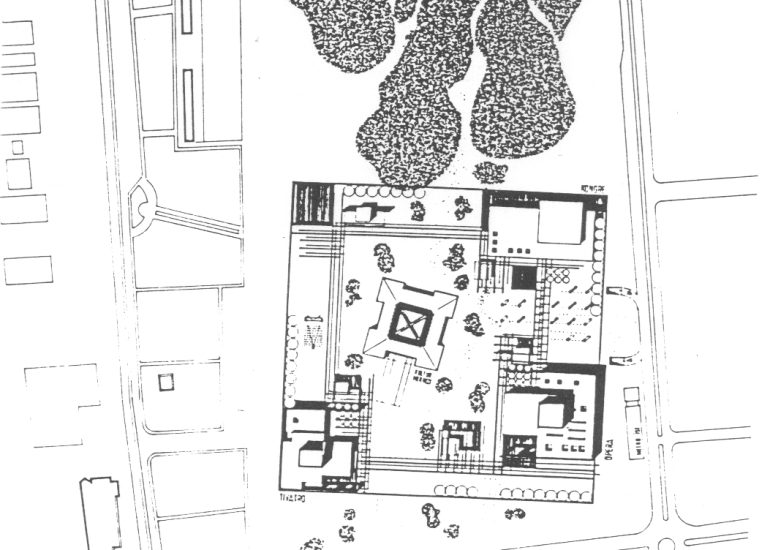

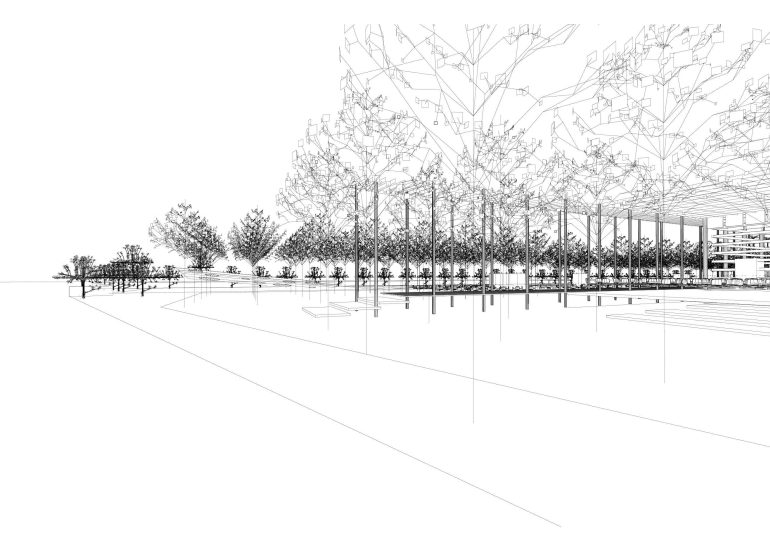

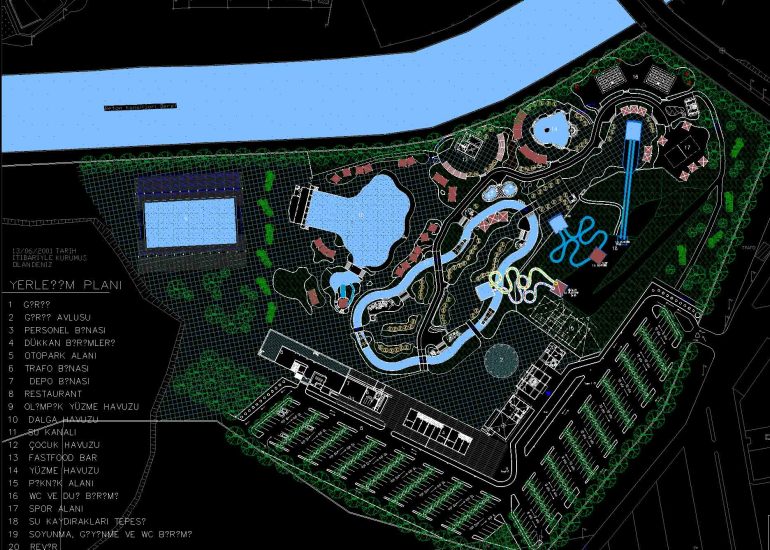

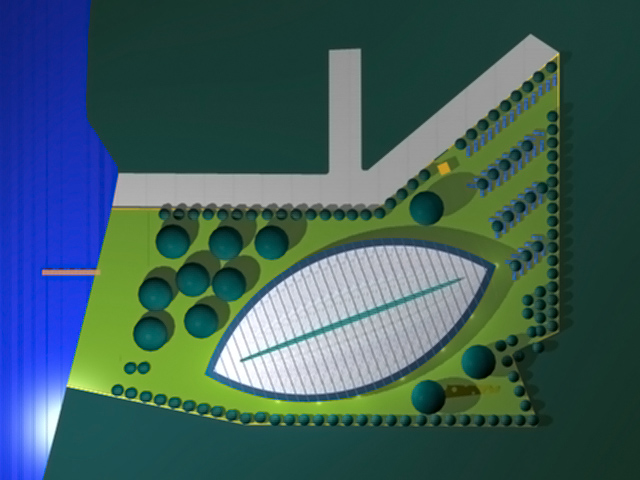

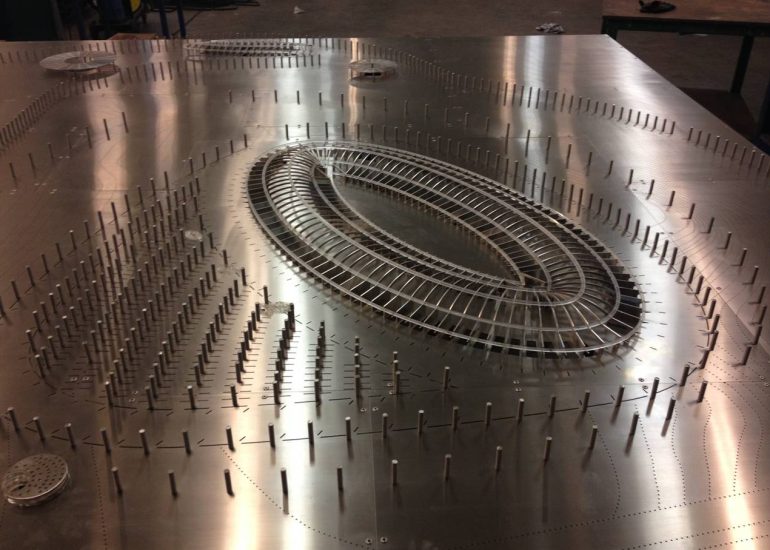

TCA did not simply design a building. They conceived a system – an alphabet of wood, able to be assembled, expanded, and read in its simplicity. The basic module: an elemental form that, in an emergency, could serve not only as a law office but also as a shelter for a family of eight. A space capable of hosting justice and offering protection – not unlike the ancient agora, where public discourse and private life converged.

This modularity is not just a technical convenience. It is a semiotic act. For what is a module if not a sign – one that only acquires meaning in context, capable of forming new sentences, or in this case: new spaces?

⸻

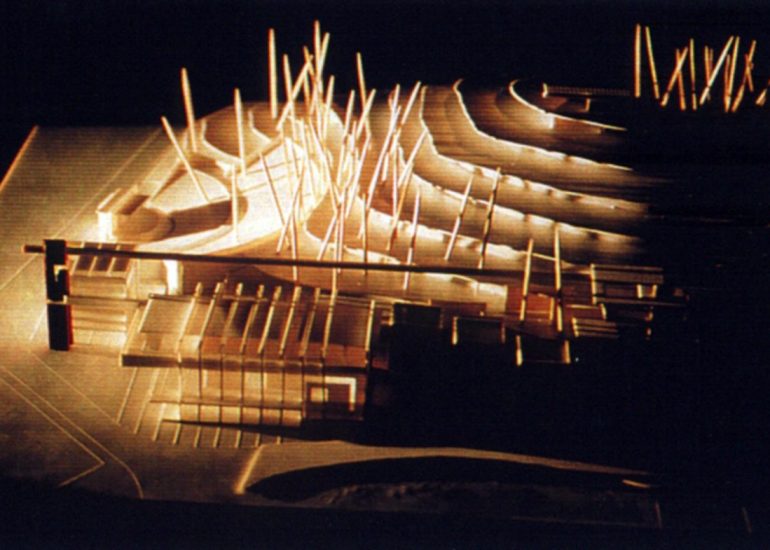

2. Wood: A Material of Memory and Hope

The choice of wood was no accident. In Turkish architectural tradition, wood is not a nostalgic material – it is a lived one. It breathes, ages, decays – and can be reused. Like a manuscript that can be erased and rewritten. Wood is an honest material – vulnerable, yet flexible. And it is precisely in this dialectic that its strength lies in earthquake-prone regions: not resistance until breaking, but resilience through adaptation.

In a world where sustainability is often reduced to a slogan, this was a rare moment of radical architectural honesty. What was built here was not static but reversible. What is a law office today can become a classroom tomorrow, a community space the day after. It is architecture of the “not-yet” – open, processual, never truly complete.

⸻

3. Time and Responsibility

TCA did not just build quickly. They thought quickly – and deeply. The urgency of the project was not a reaction born of panic, but a lived ethos: Whoever builds must know they are responsible not only for the present but for its consequences.

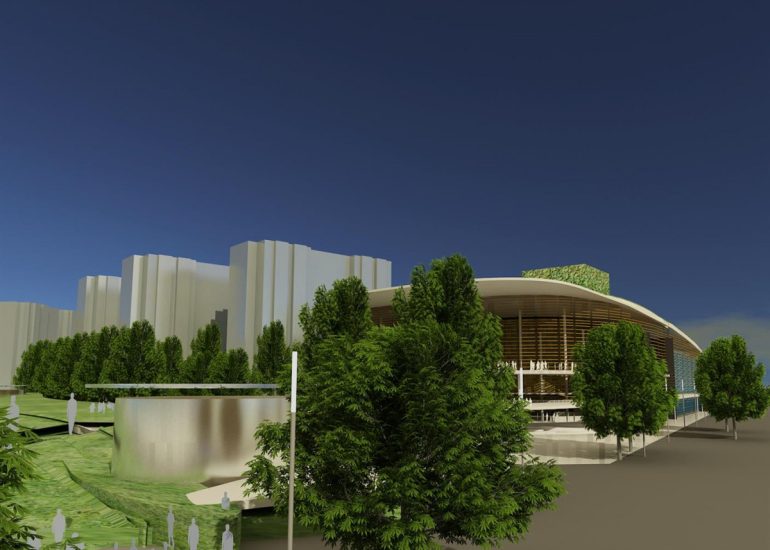

What emerged in Adapazarı was a prototype for future building: open to functional transformation, materially restrained, economically conceived, and dignified in form. Architecture as a response – not just to disaster, but to the deeper questions of our age.

⸻

4. An Ethics of Design

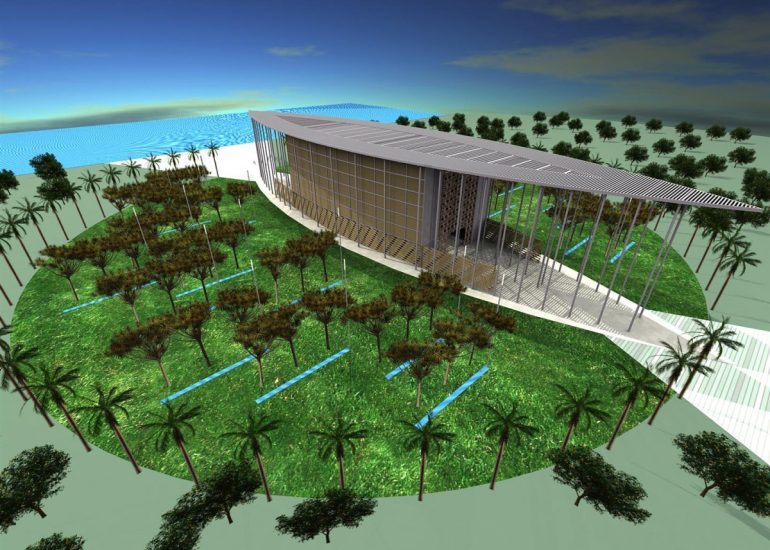

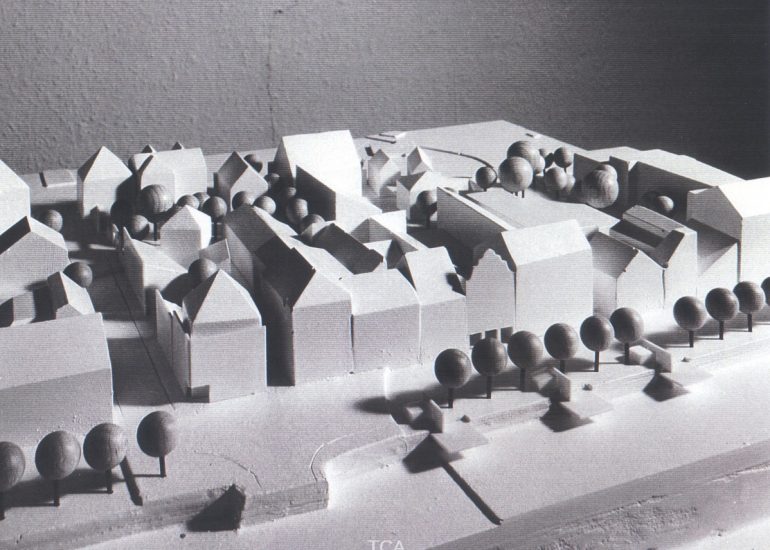

According to TCA, design must be more than functional. It must be ethically legible. In a world where landscape is treated as resource and people as statistics, design must never become a cynical act. It must tread carefully, both with what is and with what might be.

This project was not just about building temporary law offices. It was about making an argument – for an architecture that listens, adapts, disappears when no longer needed, and re-emerges elsewhere with new purpose.

⸻

Epilogue: The Invisible Foundation

Perhaps the most important part of this project was not what was seen, but what was sensed: the idea that even in transition, there is permanence; that the temporary can hold memory; and that in each module, in each beam of wood, not only spatial but also moral decisions had been inscribed.

If architecture is a language, then TCA’s design was a quiet but powerful word:

Justice needs space – even in the temporary.

A Response to Crisis, Written in Wood

When the earth moves, it is not only the foundations of cities that tremble, but also the invisible structure of meaning we call civilization. Adapazarı, 1999 – a rupture in time, a seismic trace of loss, but also of a profound need for dignity amidst collapse. In that moment, the Bars of Athens and Istanbul did not respond with a legal memorandum or a bureaucratic protocol. They responded with a gesture – an architectural one.

TCA was summoned – not merely as a provider of physical structures, but as an interpreter of a collective urgency. What emerged was more than a series of temporary law offices: it was an architectural palimpsest, written on the fractured ground of a devastated city.

⸻

1. The Module as Metaphor

TCA did not simply design a building. They conceived a system – an alphabet of wood, able to be assembled, expanded, and read in its simplicity. The basic module: an elemental form that, in an emergency, could serve not only as a law office but also as a shelter for a family of eight. A space capable of hosting justice and offering protection – not unlike the ancient agora, where public discourse and private life converged.

This modularity is not just a technical convenience. It is a semiotic act. For what is a module if not a sign – one that only acquires meaning in context, capable of forming new sentences, or in this case: new spaces?

⸻

2. Wood: A Material of Memory and Hope

The choice of wood was no accident. In Turkish architectural tradition, wood is not a nostalgic material – it is a lived one. It breathes, ages, decays – and can be reused. Like a manuscript that can be erased and rewritten. Wood is an honest material – vulnerable, yet flexible. And it is precisely in this dialectic that its strength lies in earthquake-prone regions: not resistance until breaking, but resilience through adaptation.

In a world where sustainability is often reduced to a slogan, this was a rare moment of radical architectural honesty. What was built here was not static but reversible. What is a law office today can become a classroom tomorrow, a community space the day after. It is architecture of the “not-yet” – open, processual, never truly complete.

⸻

3. Time and Responsibility

TCA did not just build quickly. They thought quickly – and deeply. The urgency of the project was not a reaction born of panic, but a lived ethos: Whoever builds must know they are responsible not only for the present but for its consequences.

What emerged in Adapazarı was a prototype for future building: open to functional transformation, materially restrained, economically conceived, and dignified in form. Architecture as a response – not just to disaster, but to the deeper questions of our age.

⸻

4. An Ethics of Design

According to TCA, design must be more than functional. It must be ethically legible. In a world where landscape is treated as resource and people as statistics, design must never become a cynical act. It must tread carefully, both with what is and with what might be.

This project was not just about building temporary law offices. It was about making an argument – for an architecture that listens, adapts, disappears when no longer needed, and re-emerges elsewhere with new purpose.

⸻

Epilogue: The Invisible Foundation

Perhaps the most important part of this project was not what was seen, but what was sensed: the idea that even in transition, there is permanence; that the temporary can hold memory; and that in each module, in each beam of wood, not only spatial but also moral decisions had been inscribed.

If architecture is a language, then TCA’s design was a quiet but powerful word:

Justice needs space – even in the temporary.

Budget: 160.000 €

Location: Adapazari, Turkey