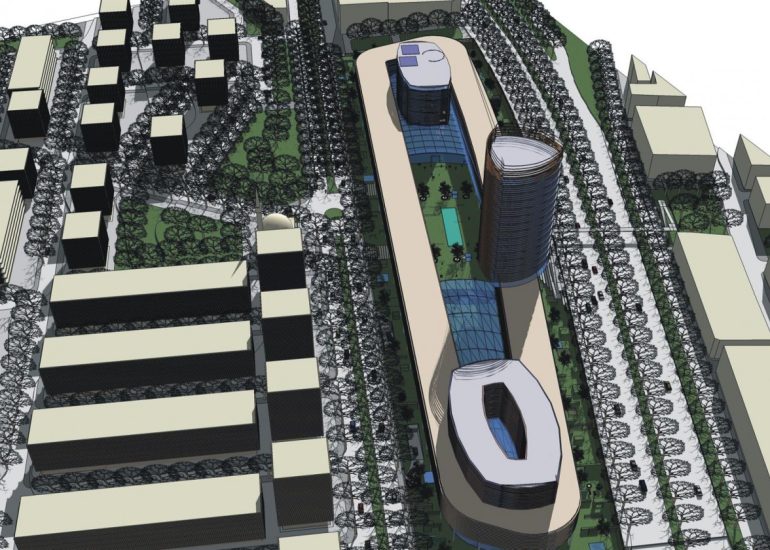

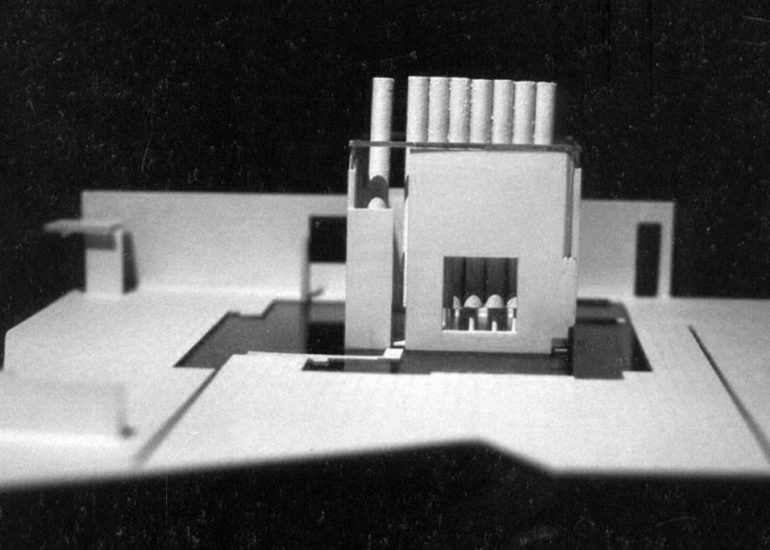

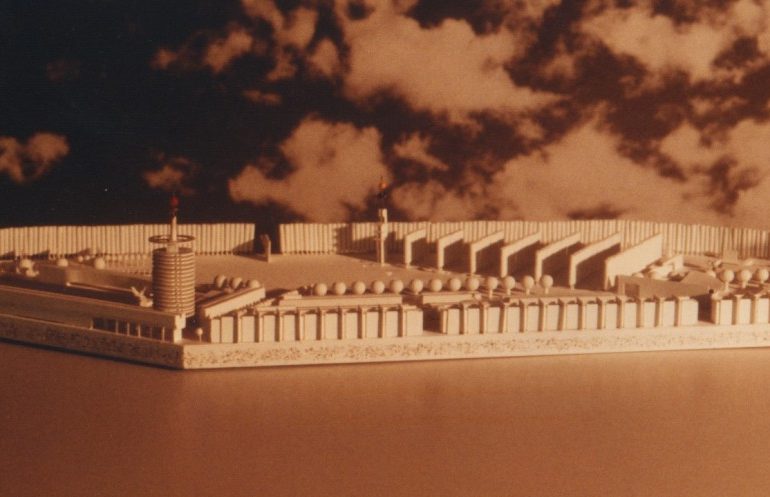

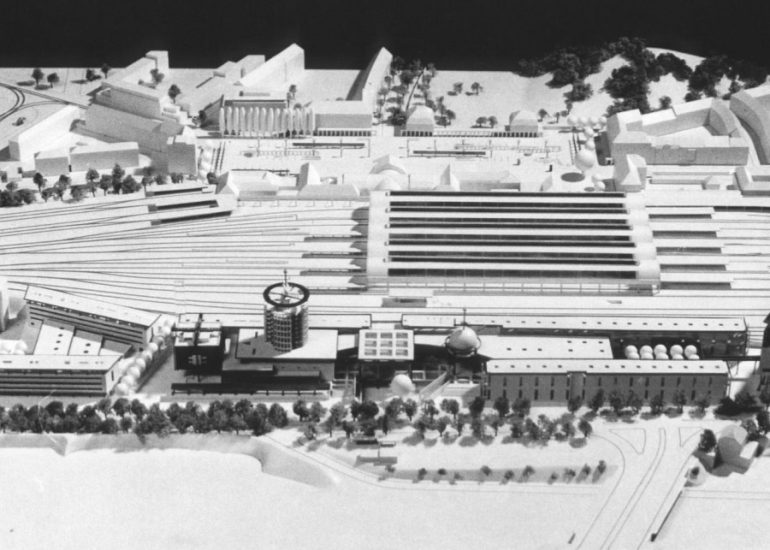

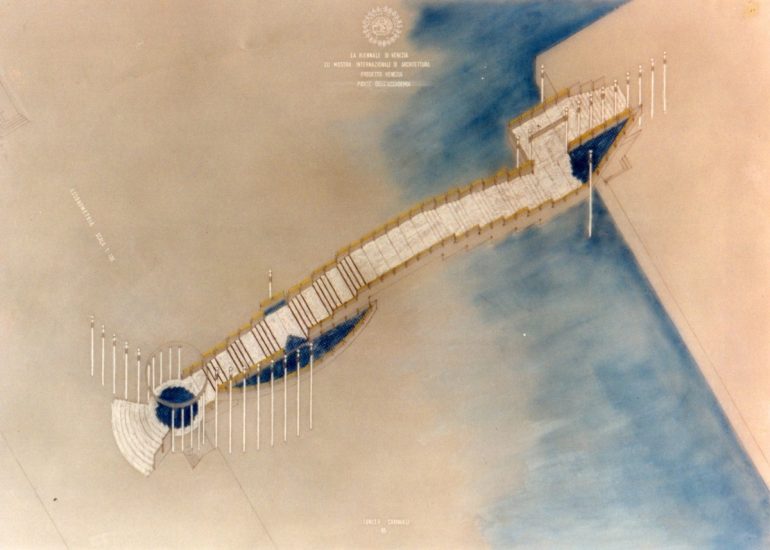

Pipe Factory Administration Building

AREA

900

YEAR

2002

A Buıldıng That Carrıes Itself On a Floatıng Archıtecture ın Zonguldak

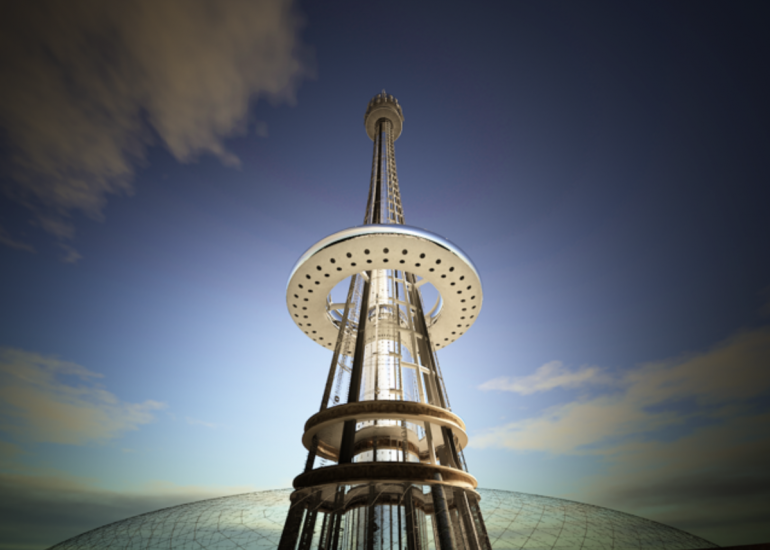

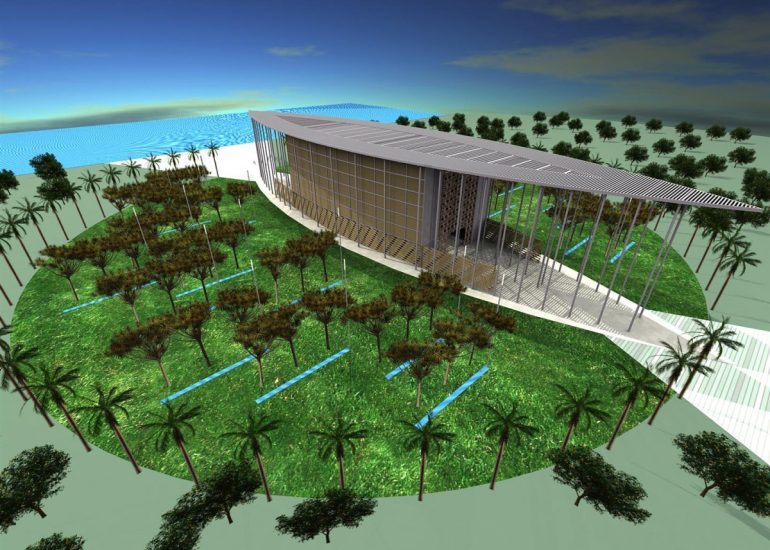

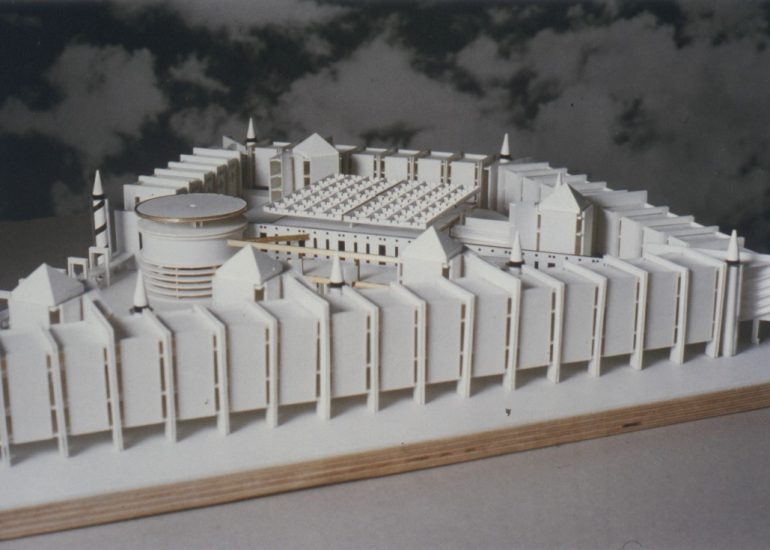

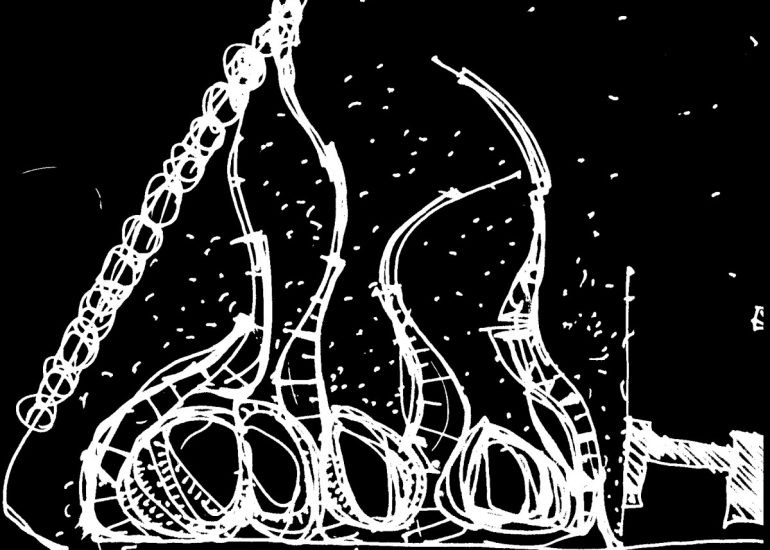

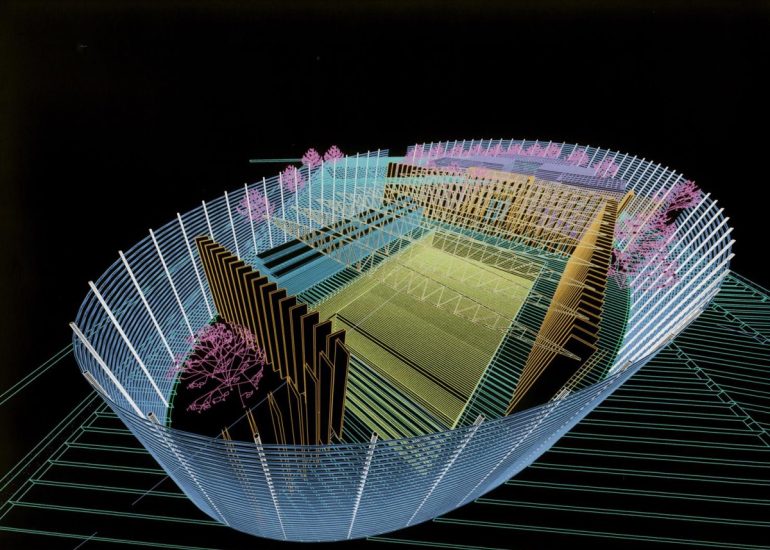

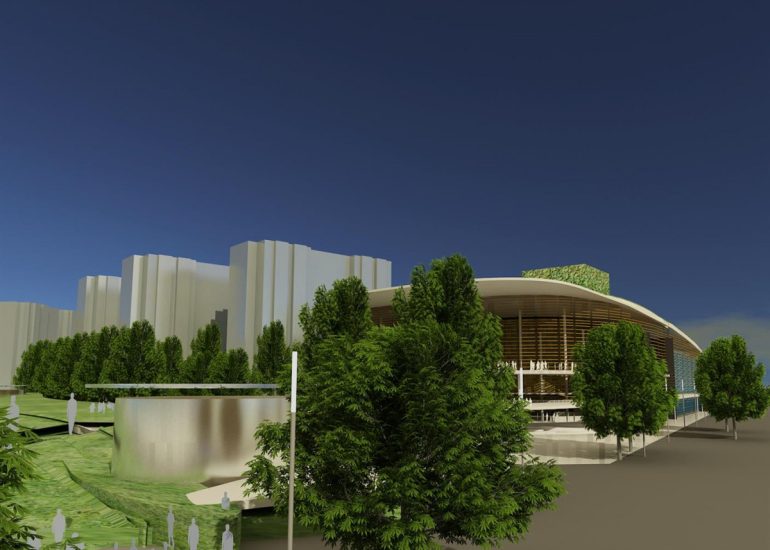

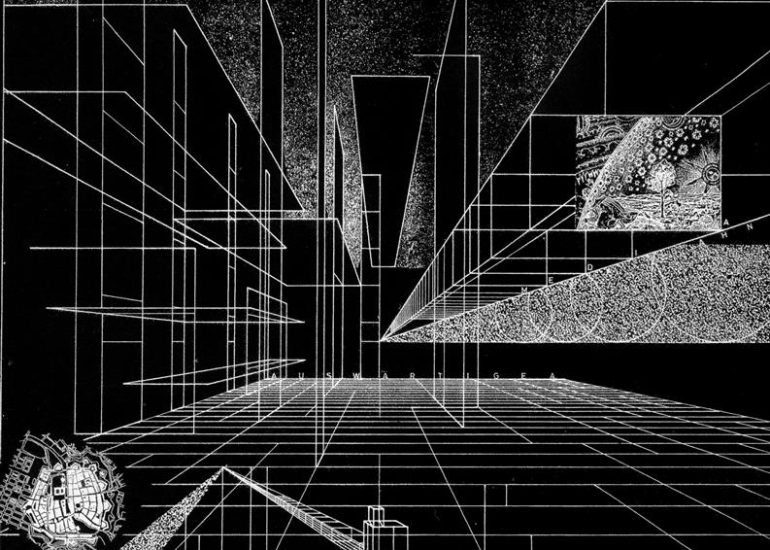

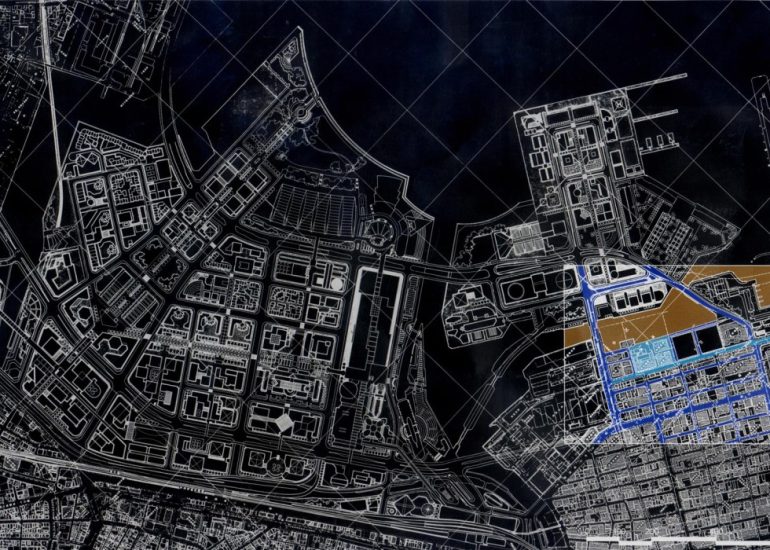

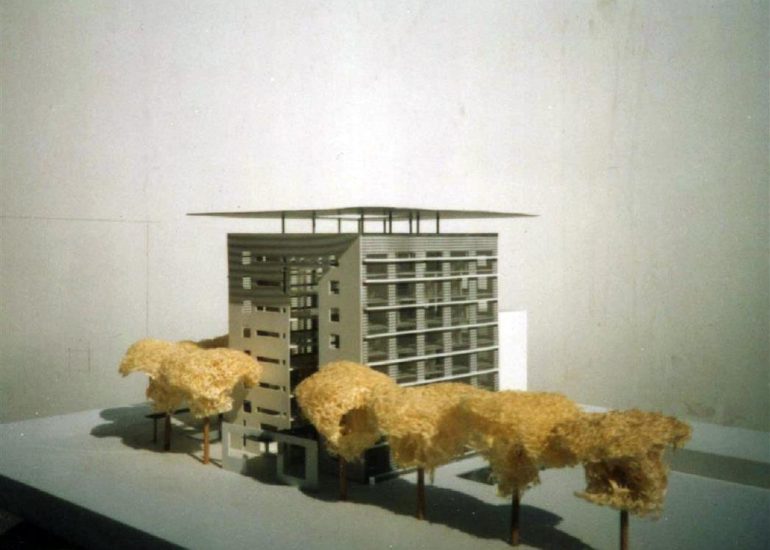

There are places where matter begins to speak for itself. Not merely as material, but as a sign, a symbol, a narrative that writes itself across space and time. In Zonguldak, a city on Turkey’s Black Sea coast, such a sign has emerged—a new headquarters building for one of the region’s largest steel pipe manufacturers. But this is no ordinary building. It is an allegory in steel, a floating story of industrial poetry.

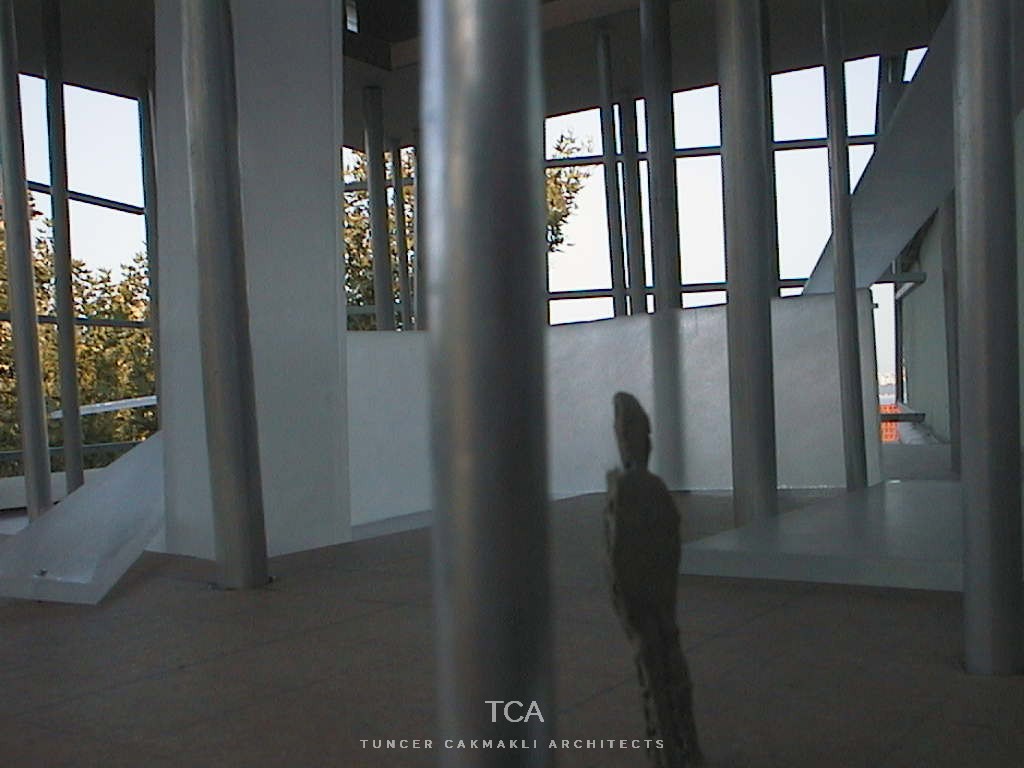

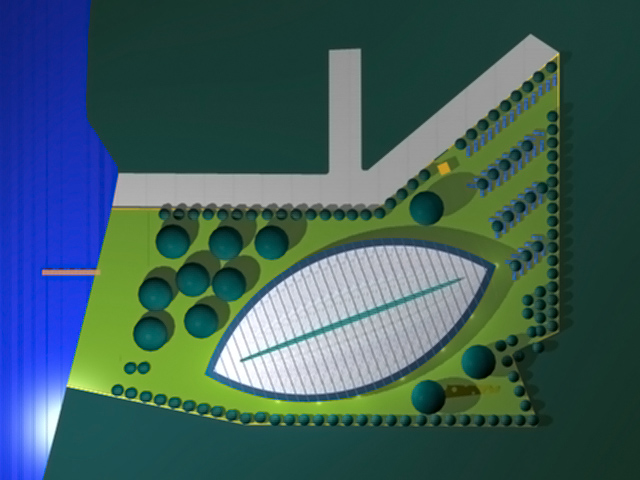

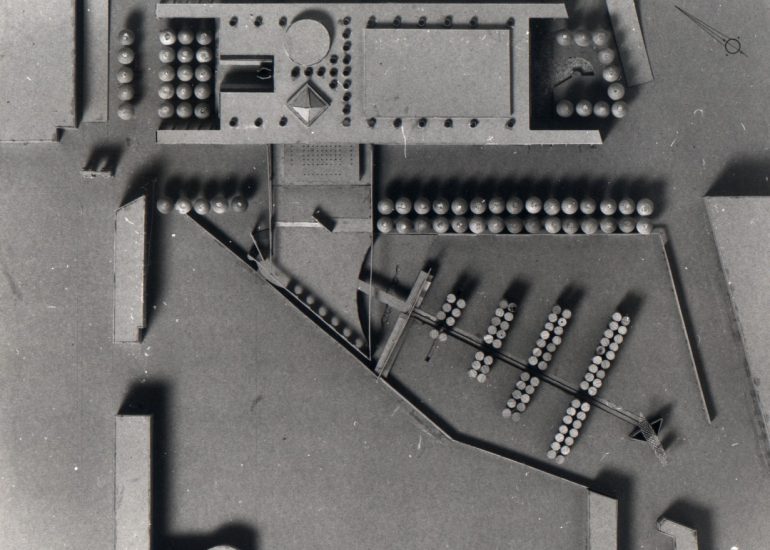

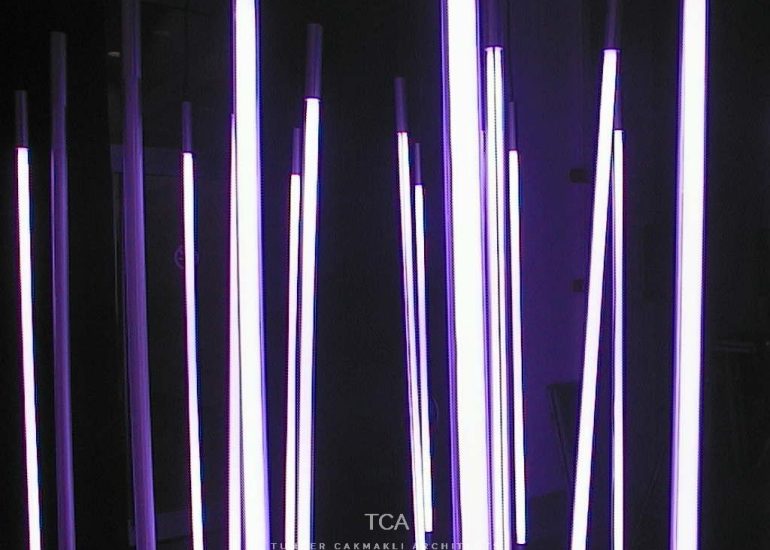

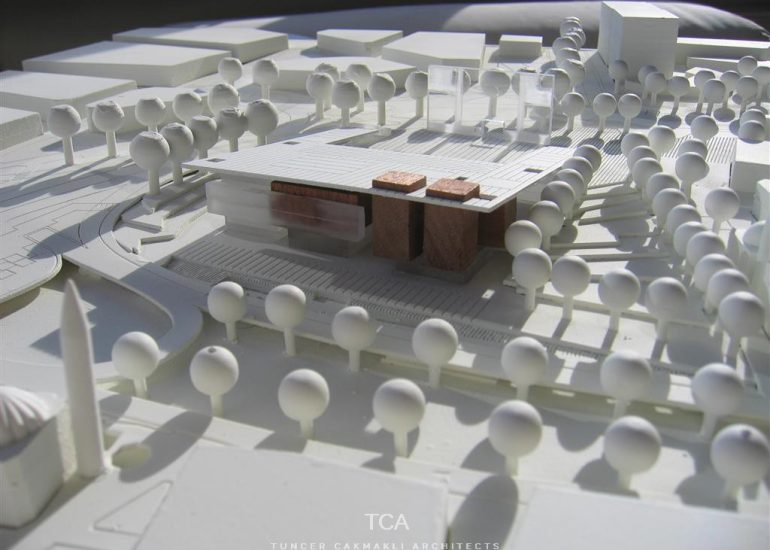

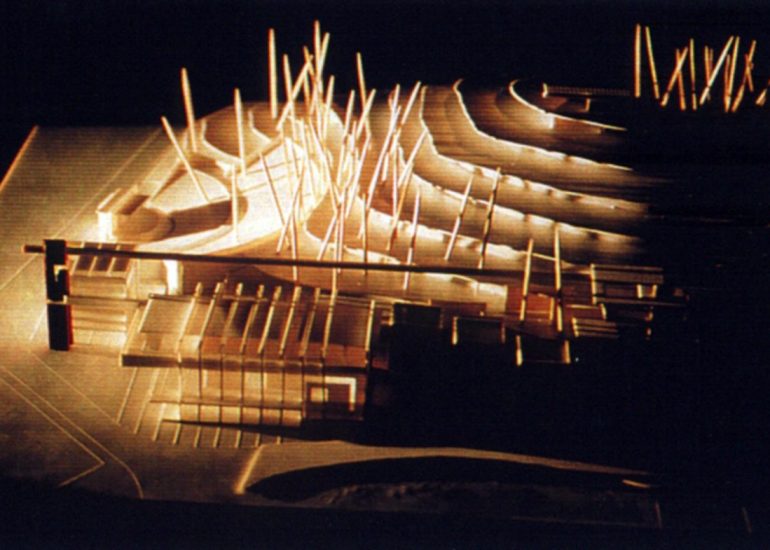

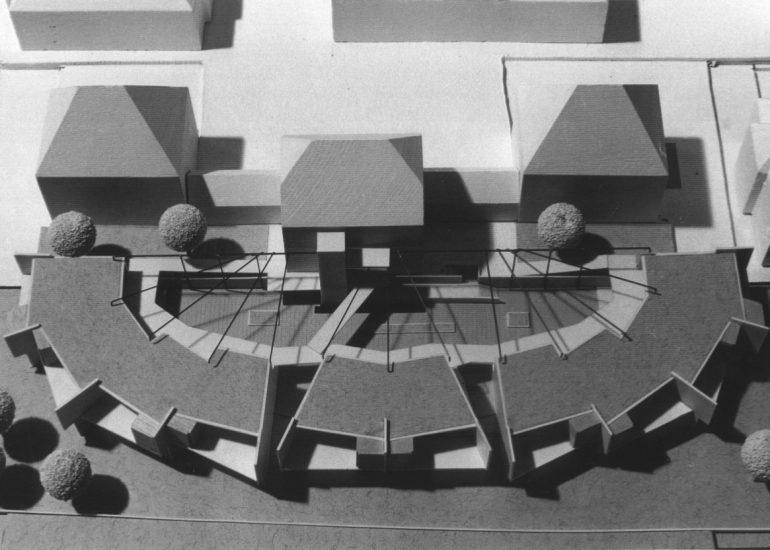

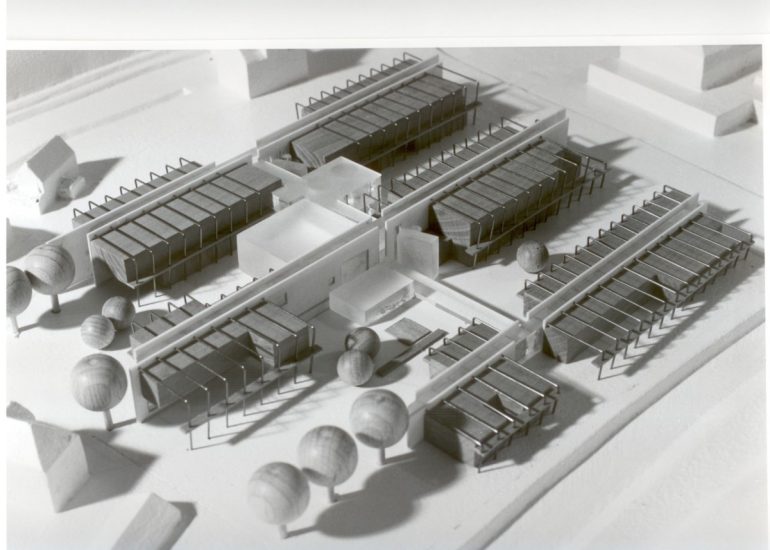

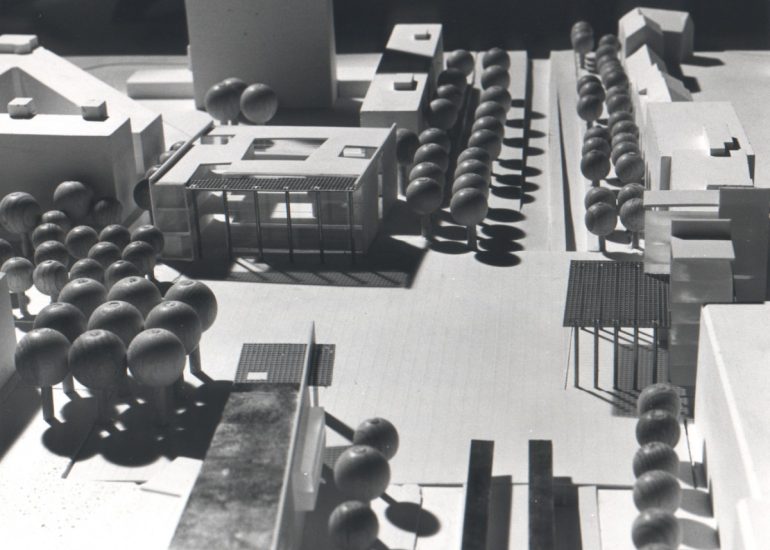

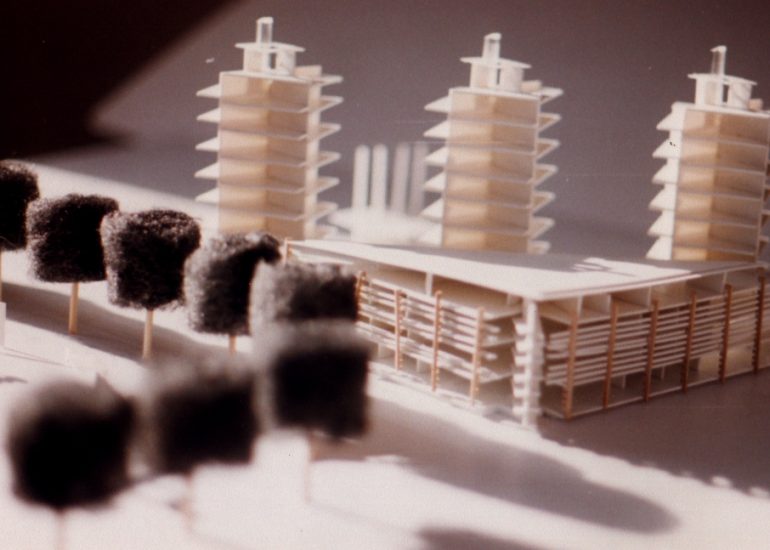

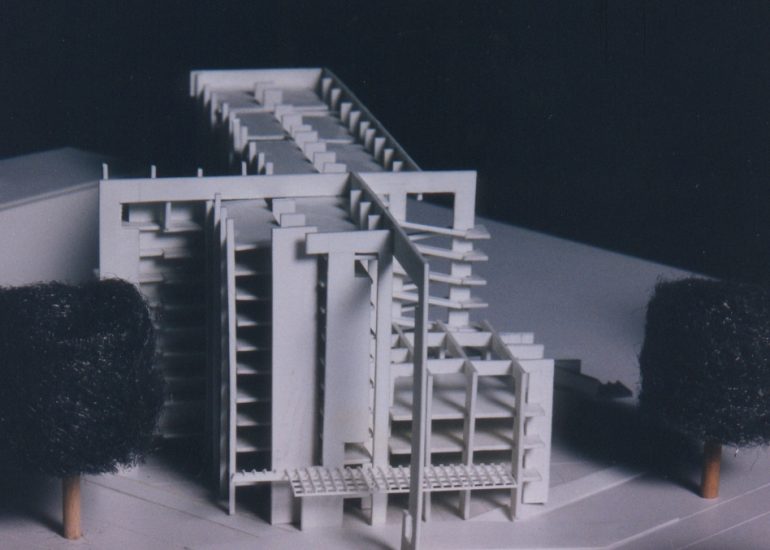

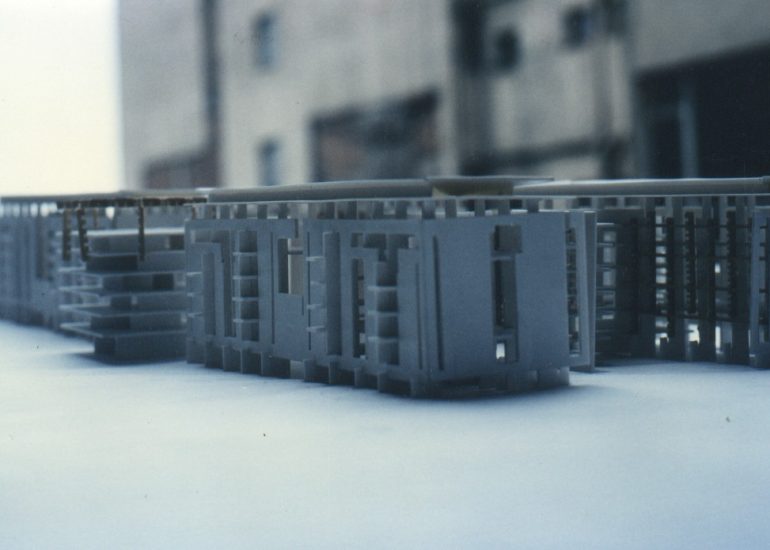

Imagine: the offices and meeting rooms of the company’s general directorate are not anchored to the ground—they are suspended in the air. Not supported by concrete or glass, but by the very thing the company produces: steel pipes. These pipes, usually hidden within the bones of infrastructure, here become the protagonists. They tell a story of origin, purpose, and transcendence.

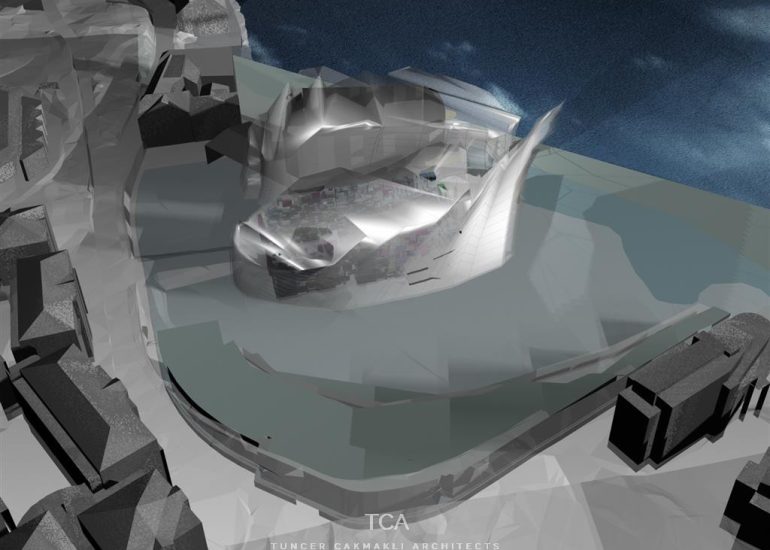

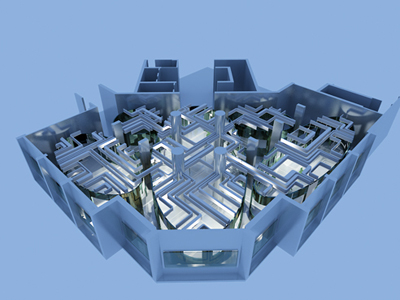

The industry lifts itself into the air. It is as if the product frees itself from its function and steps into a new semantic realm—transforming from utilitarian matter into a metaphor of lightness. The weight of steel dissolves in the symbolic gesture of weightlessness. One might say: the building floats because the idea behind it floats.

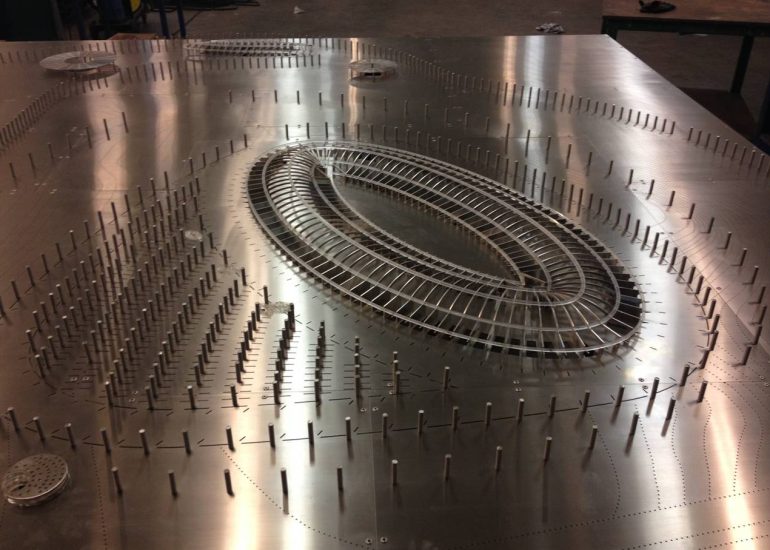

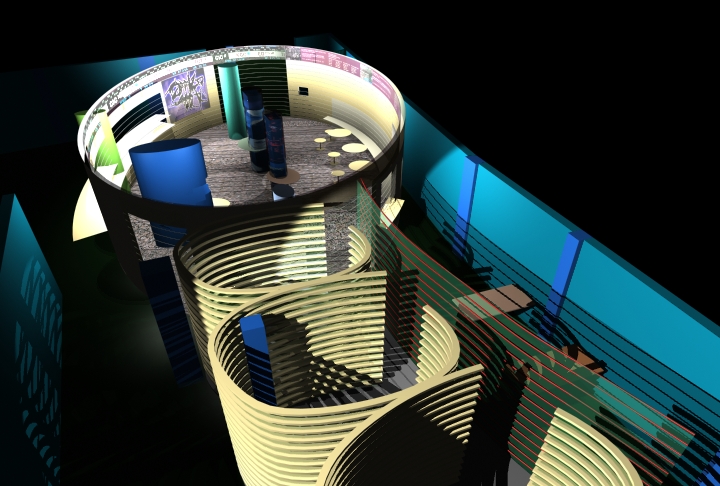

This structure does not merely make use of leftover materials—it transforms them. Waste becomes meaning, function becomes form, and material becomes message. The steel pipes carry the building just as the labor of those who shape them carries the company. It is a dialogical relationship between production and representation, between functionality and philosophy.

But what does it mean to float?

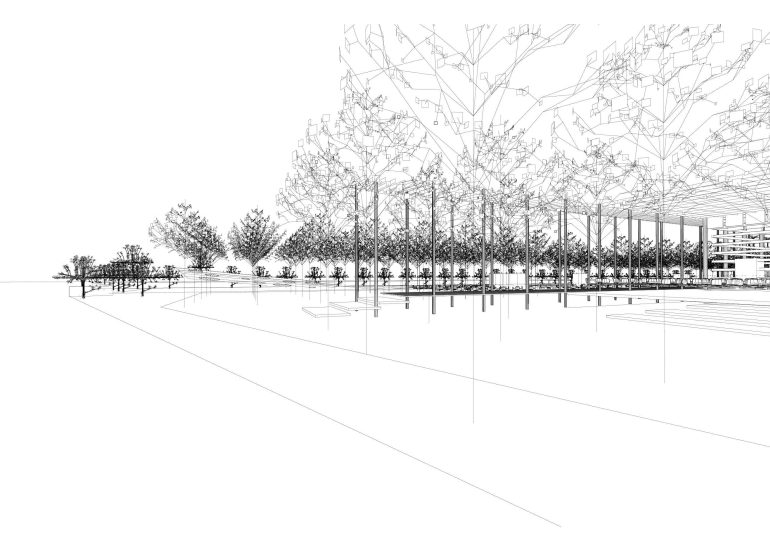

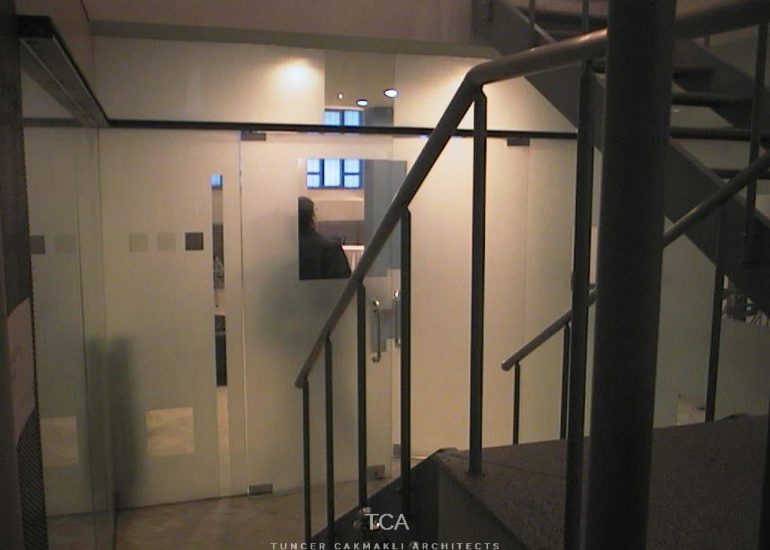

In an age where management is often isolated from the world—trapped in glass boxes above urban skylines—this building proposes a new kind of transparency. Not through glass, but through elevation. The headquarters does not look down—it looks outward. Across the production halls, across the terrain, and out toward the open sea. Work is no longer confined to artificial light but invigorated by the sea breeze. The gaze is not limited by walls but shaped by the horizon.

This building becomes a semantic system—it speaks. It speaks of lightness and overview, of material and idea, of labor and spirit. It shows that architecture is not merely the result of economic necessity, but a cultural artifact that generates, structures, and communicates meaning.

Such a building is no silent object. It is a text. And like any text in the semiotic sense, it is open to interpretation—polysemous, ambiguous, perhaps even unsettling, but deeply human.

Because what is steel if not a frozen gesture of the will to shape the world?

And what is a floating office building if not a manifesto of that very gesture?

———————————————————————————————————————————

Kendini Taşıyan Bir Yapı Zonguldak’ta HAVADA YÜZEN Bir Mimarlık Üzerine

Bazı yerler vardır ki, madde kendi hikâyesini anlatmaya başlar. Sadece bir malzeme değil; bir işaret, bir sembol, zaman ve mekânda yazılı bir anlatıya dönüşür. Türkiye’nin Karadeniz kıyısındaki Zonguldak şehrinde böyle bir işaret doğdu: bölgenin en büyük çelik boru üreticilerinden biri için tasarlanan yeni genel müdürlük binası. Ancak bu sıradan bir yapı değil. Çelikten örülmüş bir alegori, sanayinin şiirsel bir anlatımı.

Hayal edin: Genel müdürlük ofisleri ve toplantı salonları yere oturmuyor—havada asılı duruyor. Beton ya da camla değil, şirketin kendi ürettiği şeyle—çelik borularla taşınıyor. Genellikle altyapının görünmeyen unsurları olan bu borular burada anlatının kahramanına dönüşüyor. Kökenin, amacın ve dönüşümün hikâyesini anlatıyorlar.

Sanayi kendini göğe kaldırıyor. Ürün, kendi işlevinden sıyrılıp yeni bir anlamsal düzleme taşınıyor—kullanım malzemesinden hafifliğin metaforuna dönüşüyor. Çeliğin ağırlığı, ağırlıksızlık jesti içinde eriyor. Denebilir ki: bu yapı uçuyor, çünkü fikri de uçuyor.

Bu yapı sadece üretim fazlası malzemeyi kullanmıyor—onu dönüştürüyor. Atık anlam kazanıyor, işlev biçime dönüşüyor, malzeme mesaj halini alıyor. Çelik borular binayı taşıyor; tıpkı onları şekillendiren emeğin şirketi taşıdığı gibi. Bu, üretim ile temsil, işlevsellik ile felsefe arasında kurulan diyalojik bir ilişkidir.

Peki, “yükselmek” ya da “yüzer olmak” ne demektir?

Yönetimin genellikle dünyadan izole olduğu bir çağda—kent manzaralarının üzerinde, cam kutulara hapsolmuşken—bu yapı başka bir şeffaflık öneriyor. Camla değil, yükseklikle. Genel müdürlük yapısı yukarıdan bakmıyor; uzağa, öteye bakıyor. Üretim alanlarının, fabrikanın, arazinin üzerinden geçerek Karadeniz’e uzanıyor. Çalışma sadece yapay ışıkla sınırlı değil artık; deniz meltemiyle tazeleniyor. Bakış duvarlarla sınırlanmıyor; ufukla şekilleniyor.

Bu bina bir anlam sistemine dönüşüyor—konuşuyor. Hafiflikten ve bakıştan, maddeden ve fikirden, emekten ve ruhtan söz ediyor. Gösteriyor ki mimarlık yalnızca ekonomik bir zorunluluğun sonucu değil; anlam üreten, anlamı yapılandıran ve aktaran bir kültürel nesnedir.

Böyle bir yapı sessiz bir nesne değildir. O bir metindir. Ve her metin gibi—özellikle göstergebilimsel anlamda—yorumlamaya açıktır: çok anlamlı, muğlak, belki rahatsız edici ama özünde insanidir.

Çünkü çelik dediğimiz şey nedir ki, dünyayı biçimlendirme iradesinin donmuş bir jestinden başka?

Ve havada yüzen bir ofis binası nedir ki, bu jestin mimari bir manifestosundan başka?