Ecumenical Church

Year

1986

Prof.PAUL SCHÜTZ-Rainer Maul /-Freelance Architect Tuncer Cakmaklı

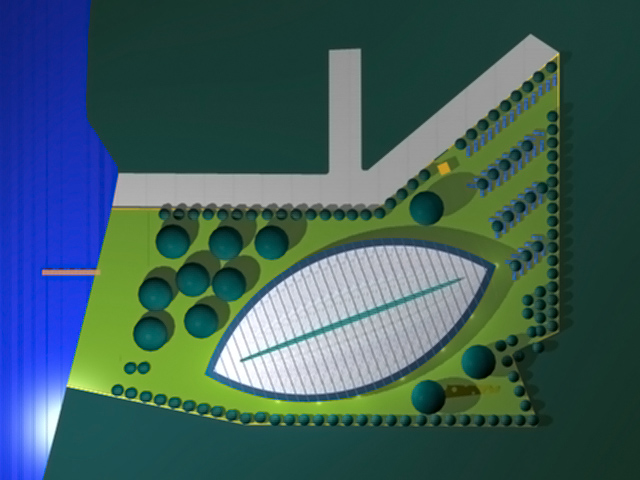

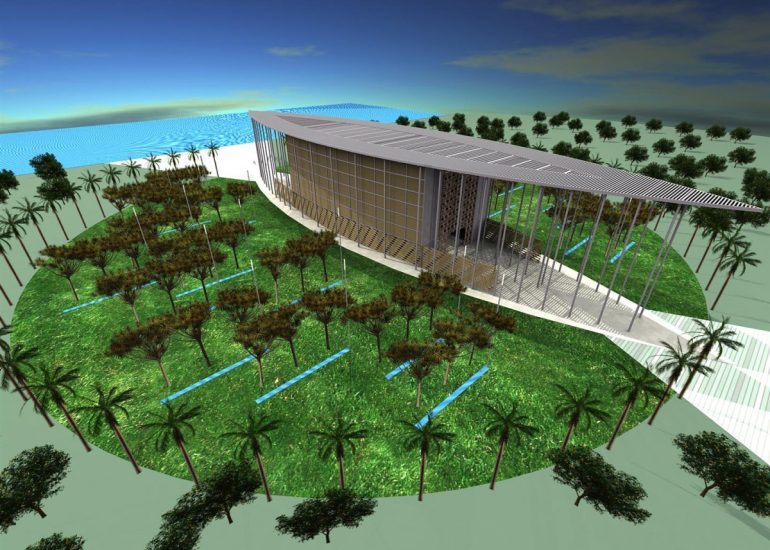

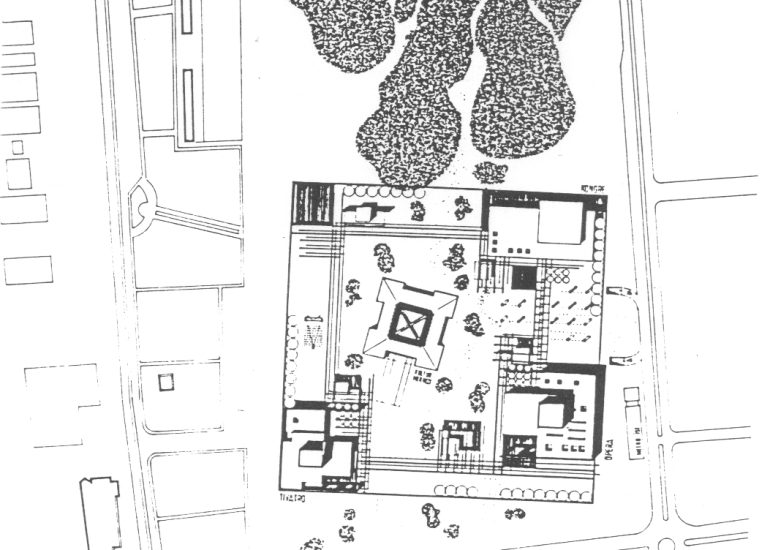

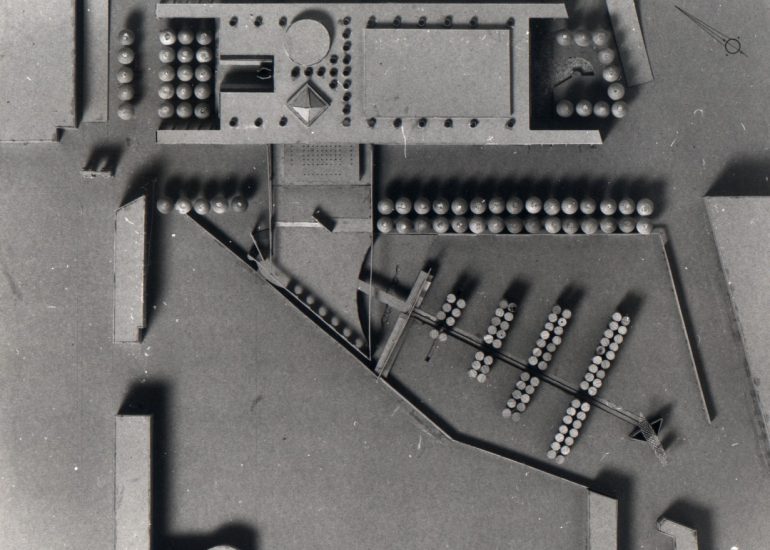

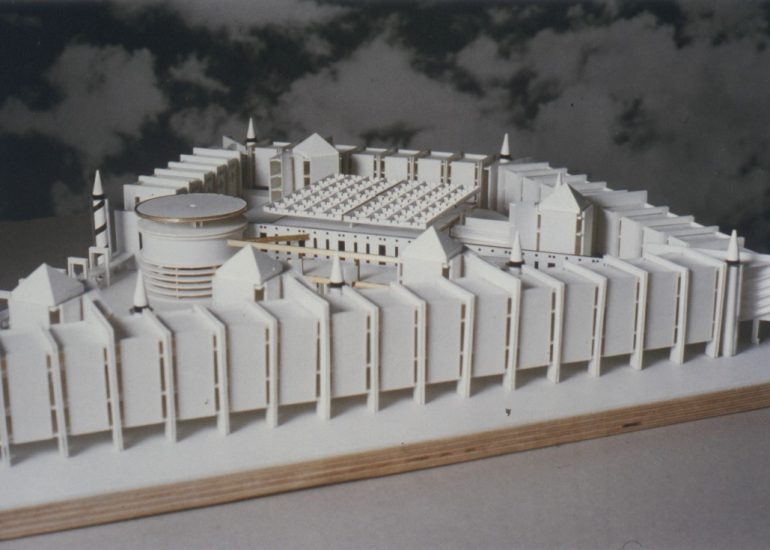

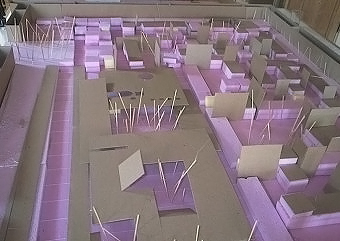

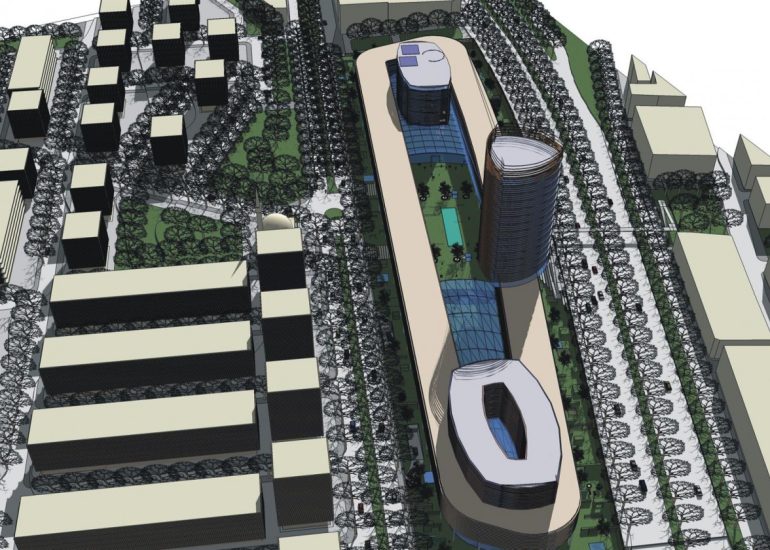

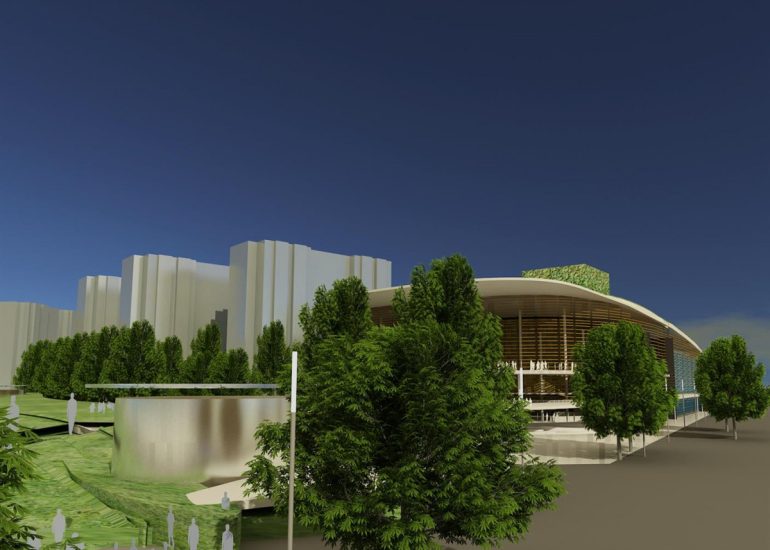

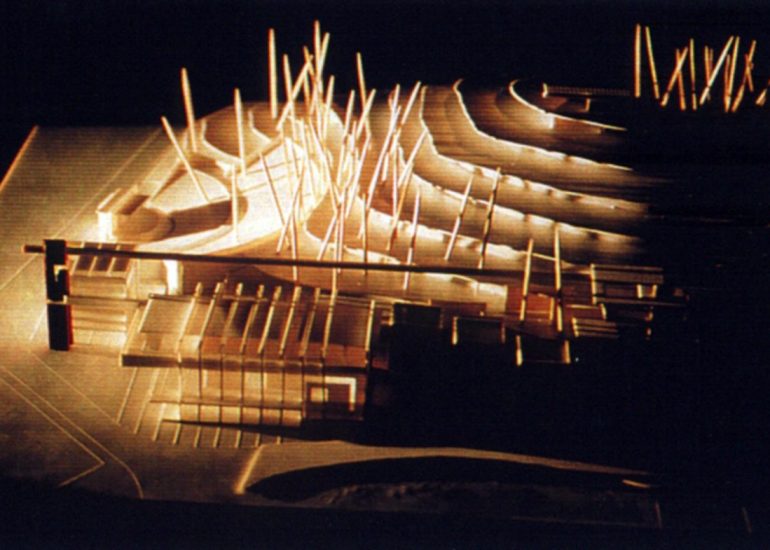

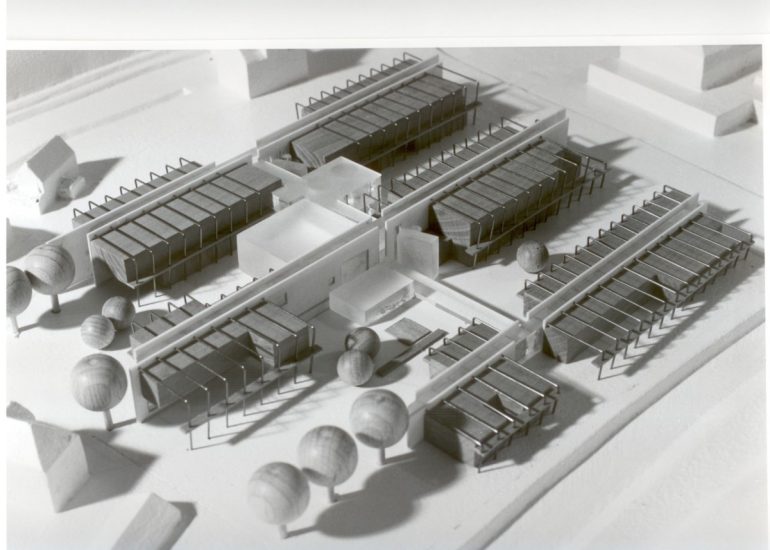

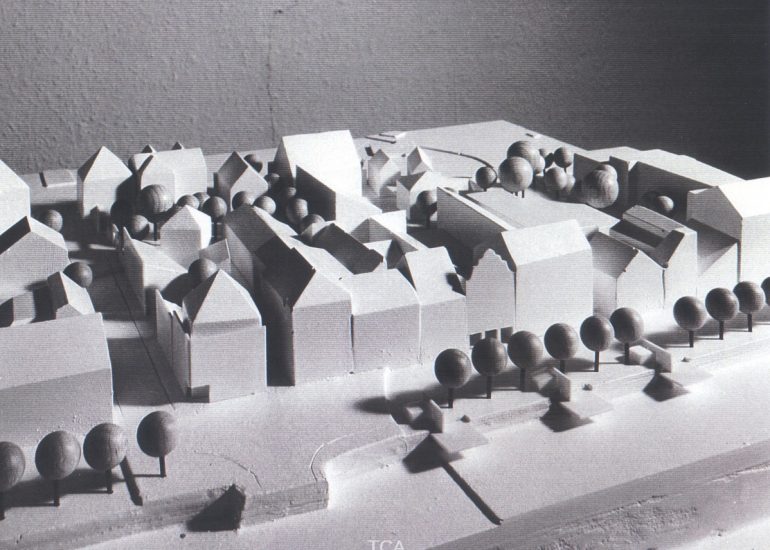

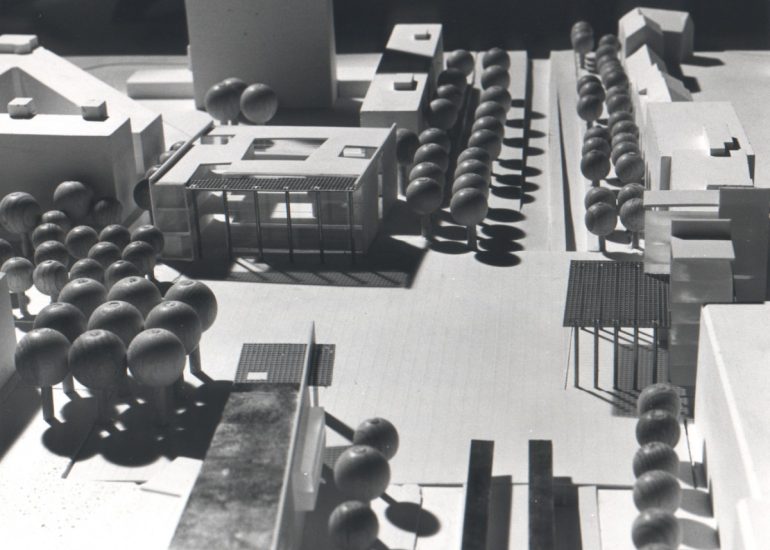

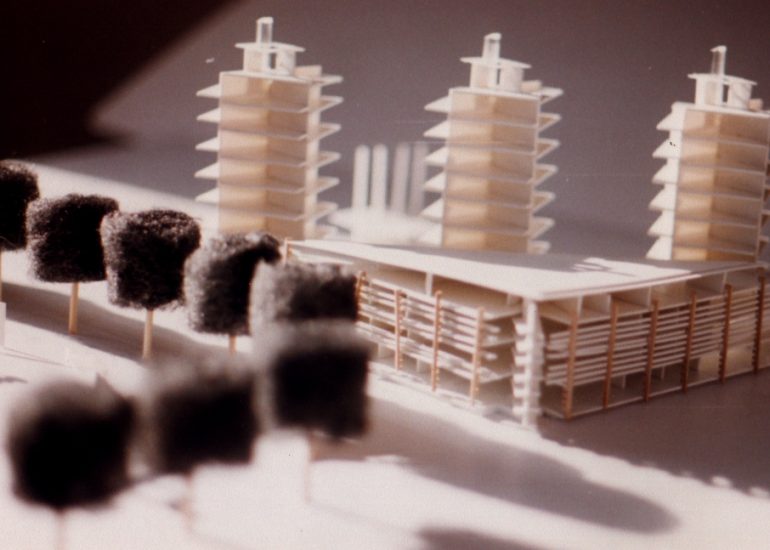

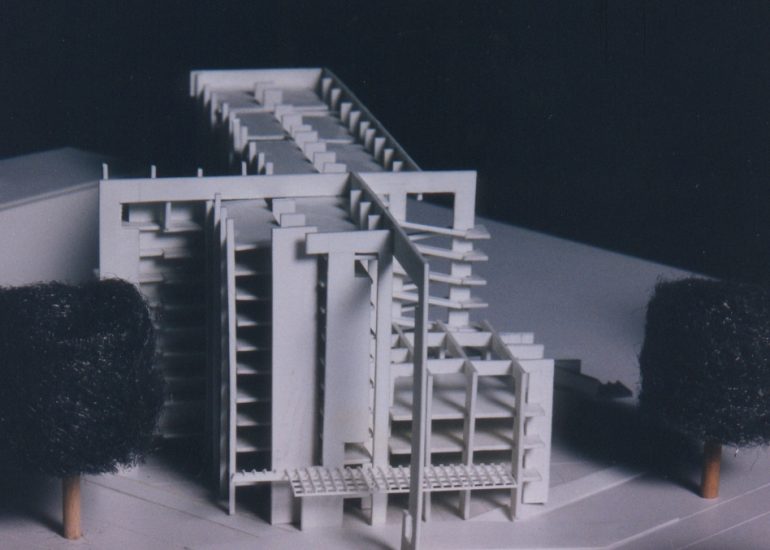

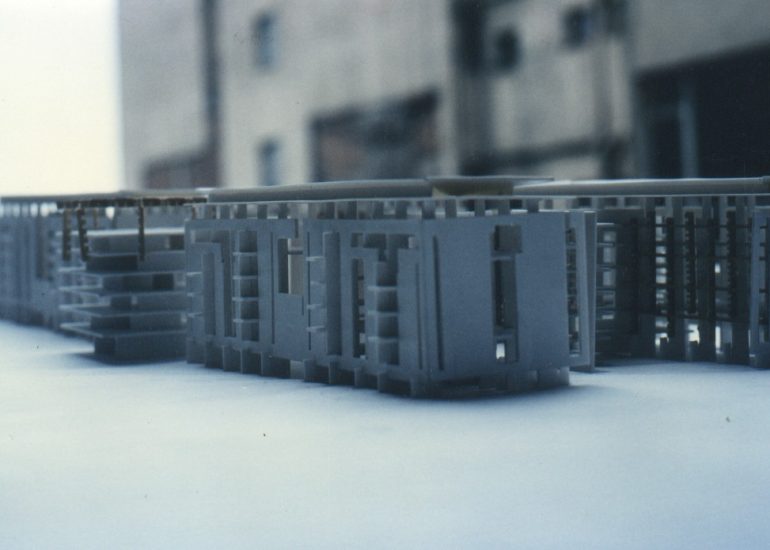

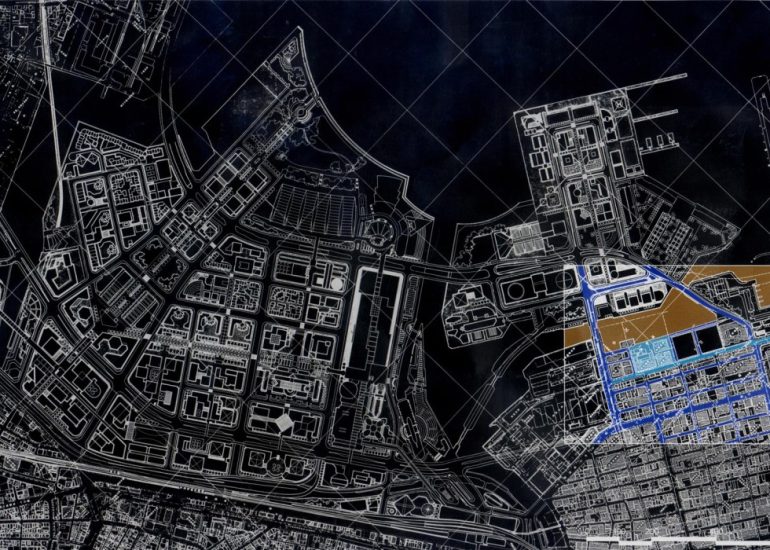

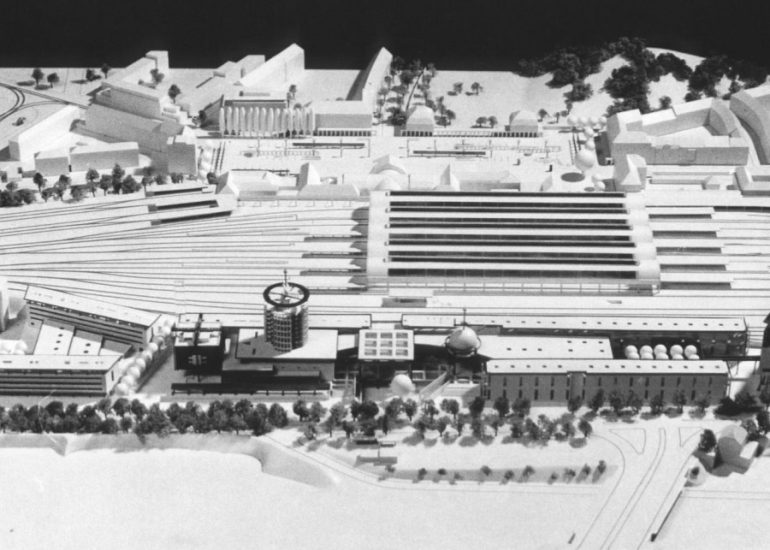

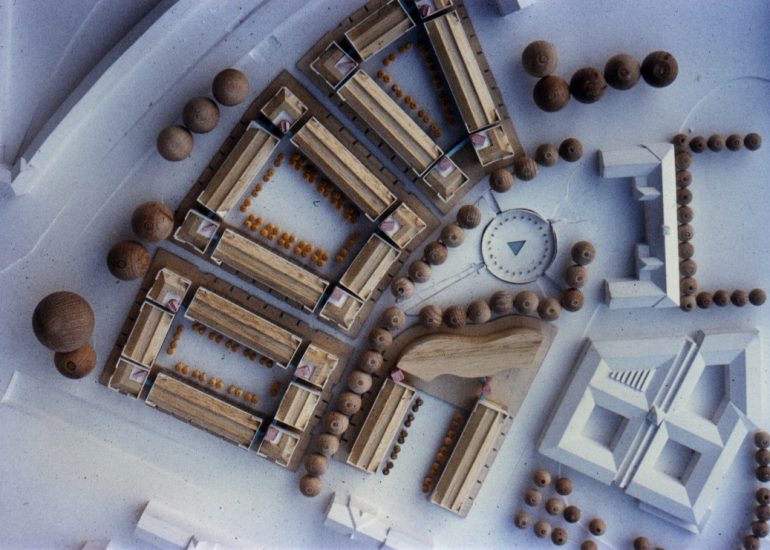

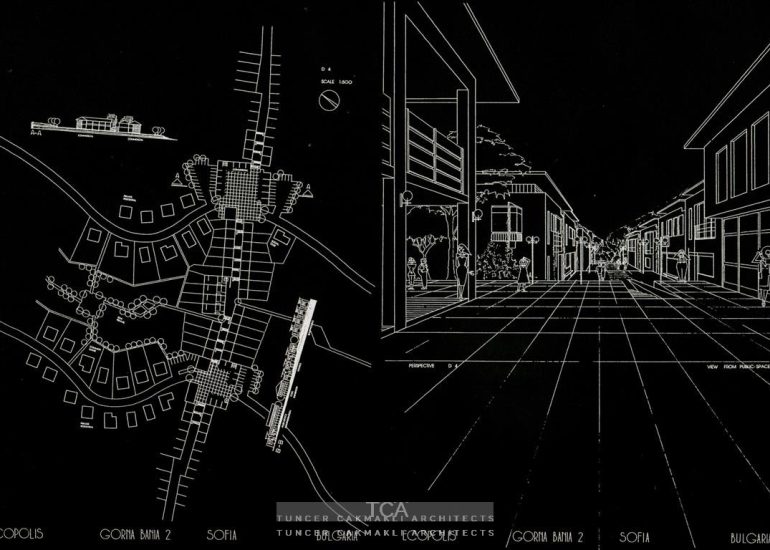

A church which can be used simultaneously by the Catholic and Protestant communities.

The semi-symmetrical design of the church allows for the two communities to have separate or joint worship services as circumstances dictate.

(Freelance Architect for Prof. Paul Schütz & Rainer Maul Architects.)

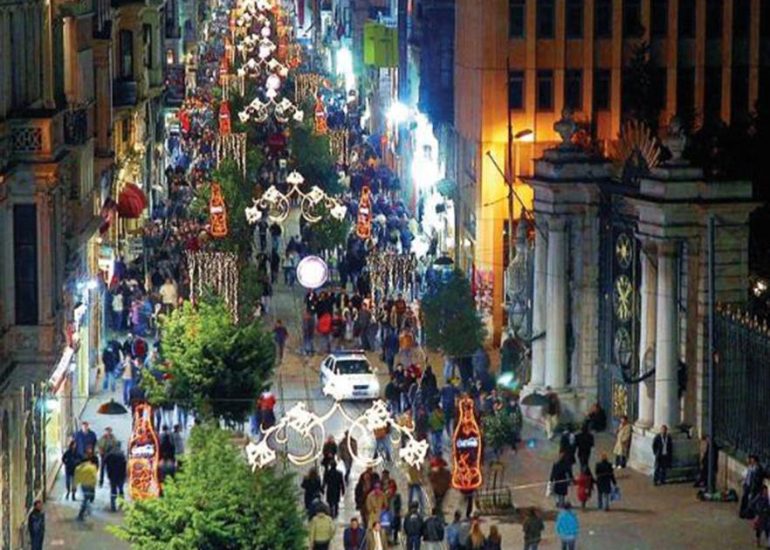

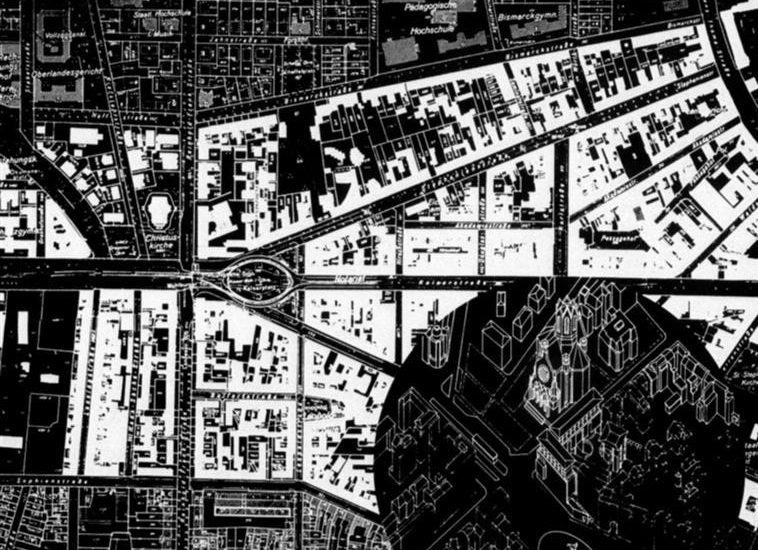

Location: Karlsruhe, Germany

Between Two Altars: Ecumenısm as an Archıtecture of Hope

The split between Catholics and Protestants—two faces of the same Christian origin—was never merely a doctrinal disagreement over justification, the Eucharist, or indulgences. It was, like every schism, a psychological act. A quiet mistrust that found its way into physical form: separate churches, separate rituals, separate families.

The apple of discord thrown by Luther into the Roman window did not only lodge itself in the Vatican; it rolled into the living rooms of ordinary believers. And when a Catholic daughter fell in love with a Protestant boy, not only the heart trembled, but the foundation of family peace. A wedding—the moment of unity—became a stage for difference. Two denominations, one promise—but which altar?

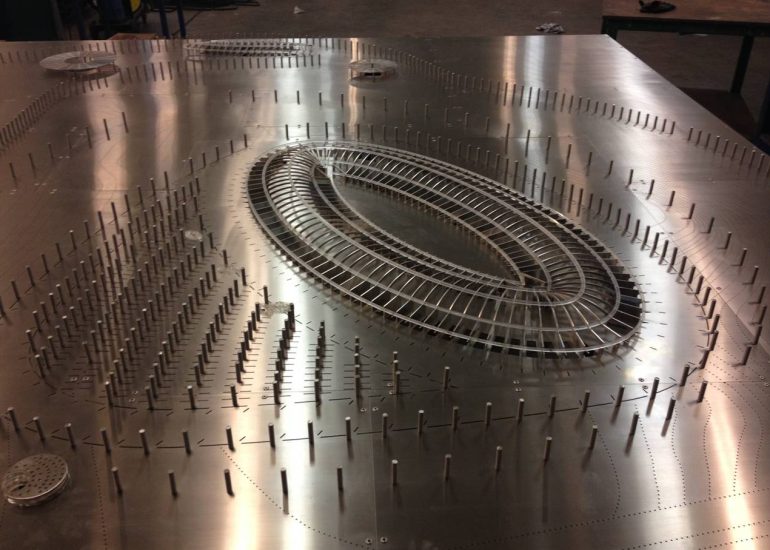

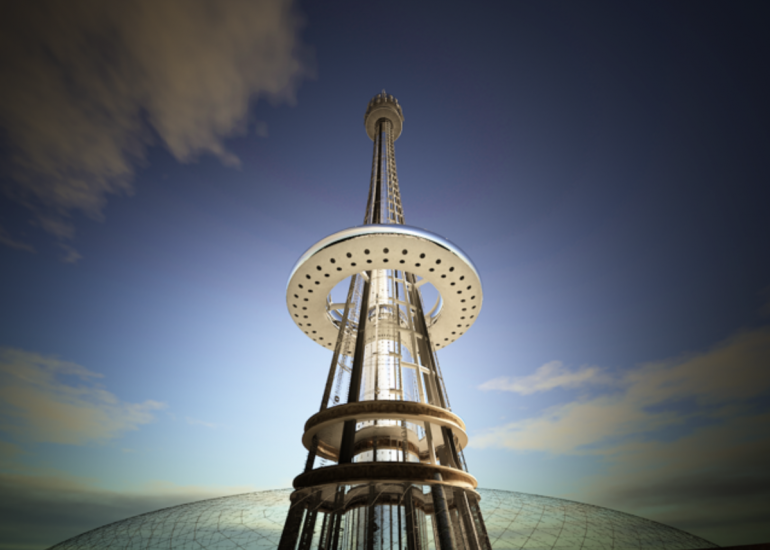

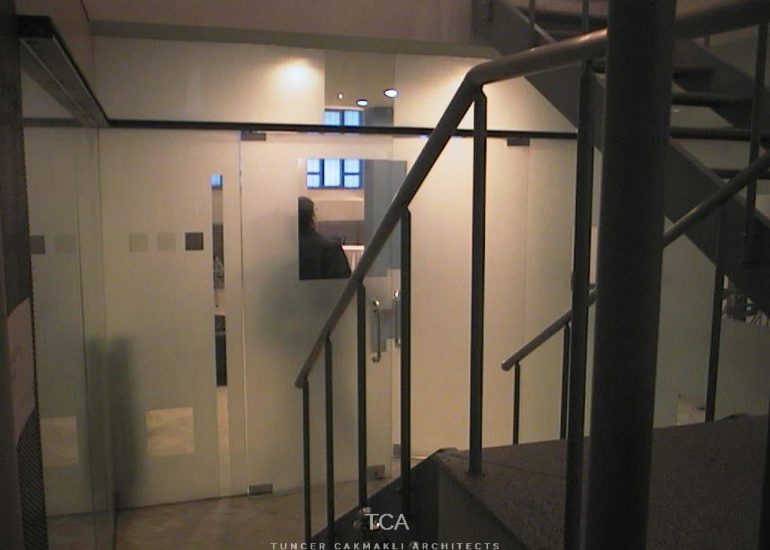

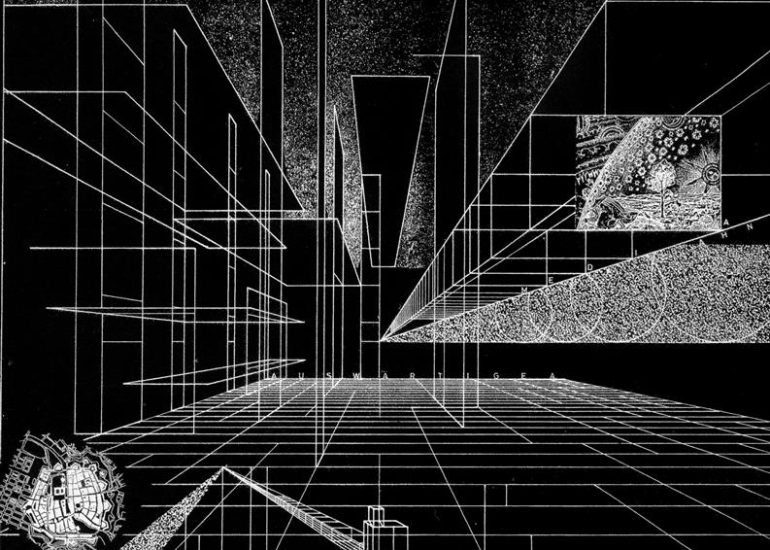

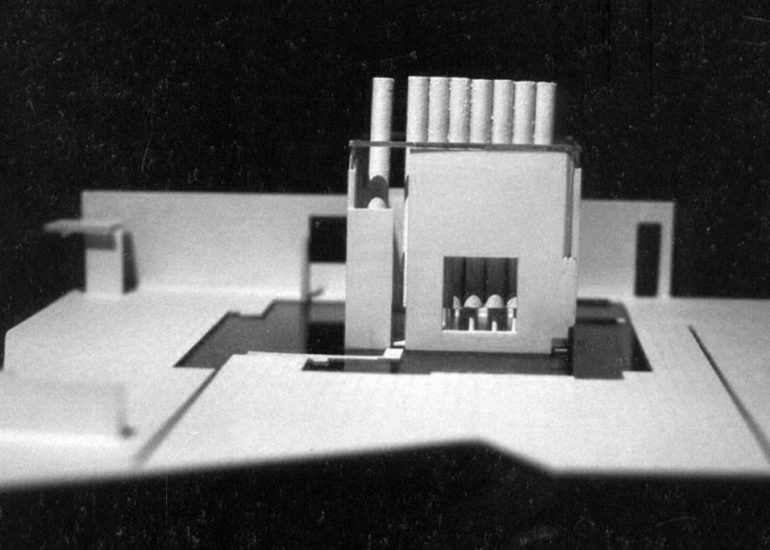

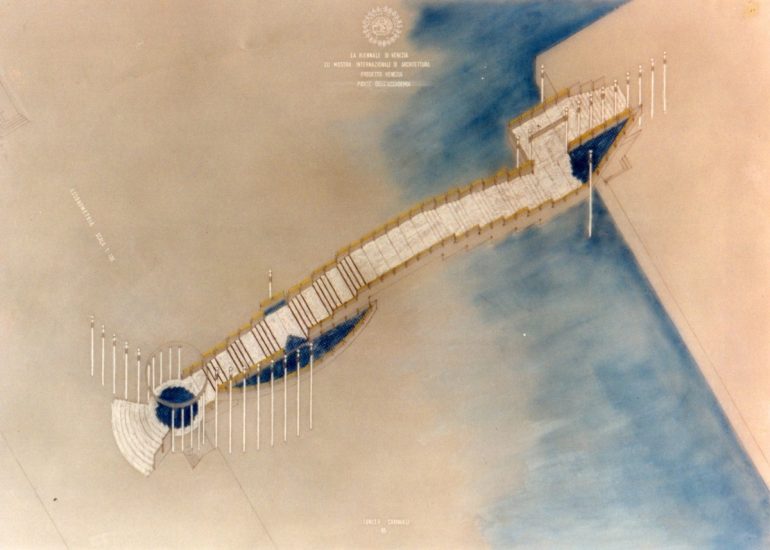

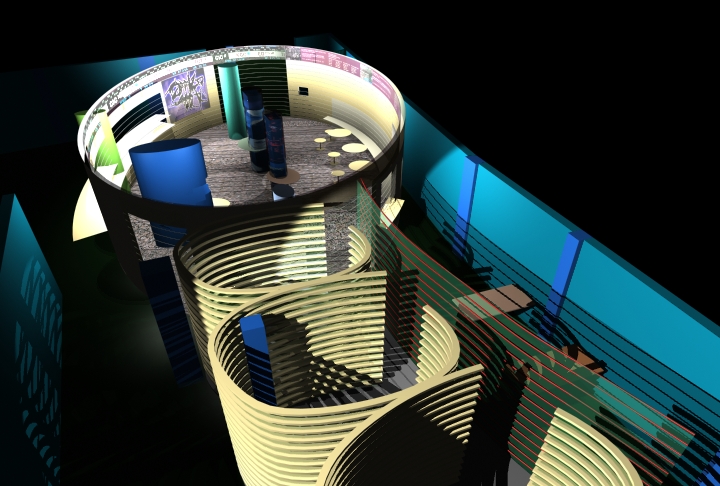

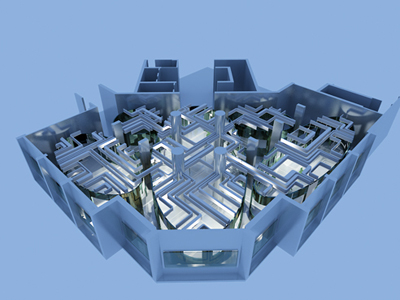

The Ecumenical Church in Karlsruhe-Oberreut is not just a building. It is a thought cast in stone, a semantic bridge between theological languages. It carries within it a paradoxical idea: separation that enables unity. Two prayer rooms—back to back—like twins who cannot see each other, but share the same heartbeat. And in between: the third space.

A space that is more than a passage. It is the place of encounter, of library, of entrance, of dialogue. It is the room where a Catholic-Protestant wedding becomes possible without betrayal—of faith or of family. The walls open. The chairs turn. And what once seemed theologically irreconcilable becomes architecturally tangible.

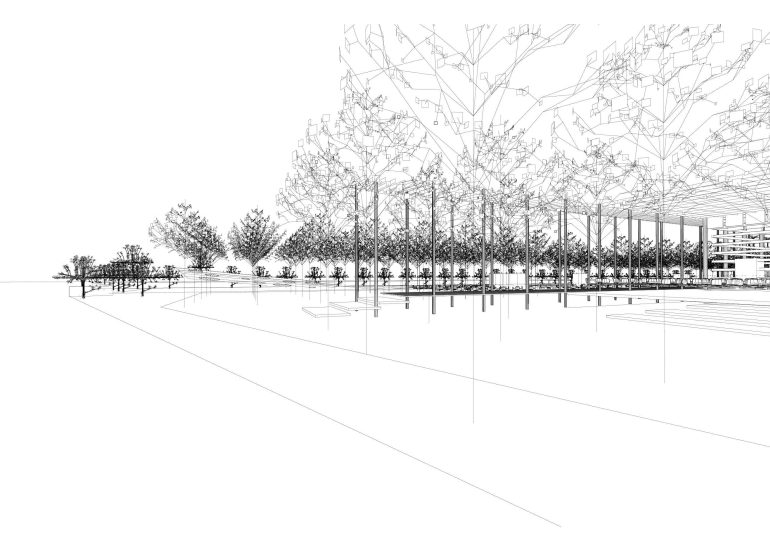

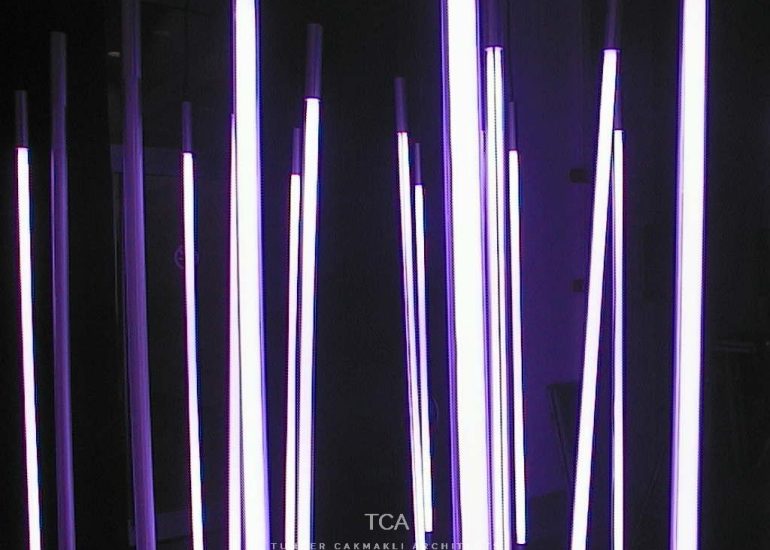

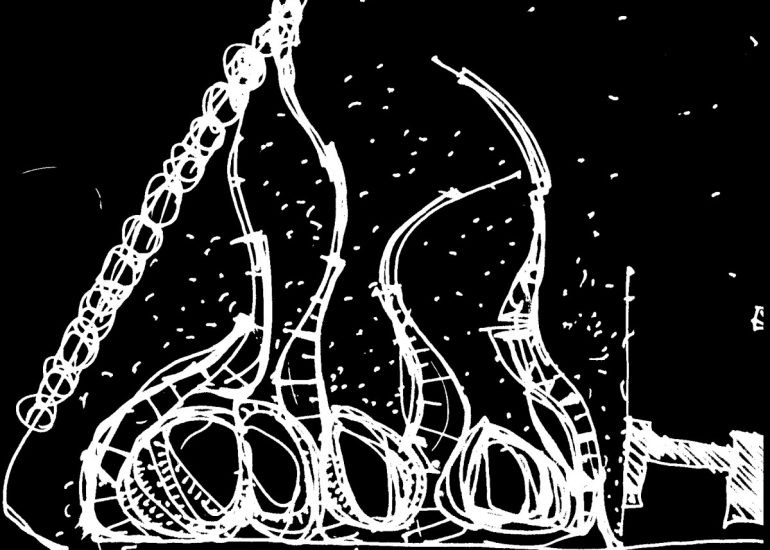

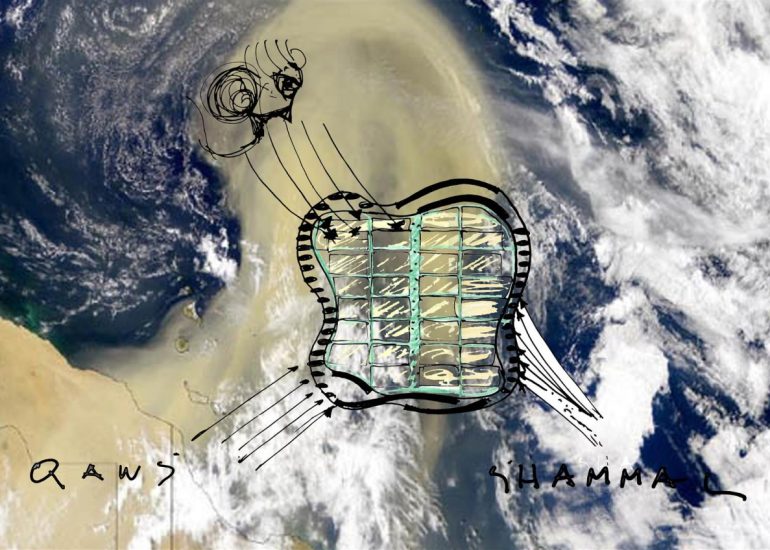

The architecture itself preaches here—without words, but not without effect. Materials have been chosen as if diplomacy were being built. Light falls not by accident, but as a sign. Everything carries meaning, because everything carries hope.

To say it with a semiotic smile: this house of God is a text. And this text does not say “Either – Or,” but “Both – And.” It is not a palace of tolerance—because tolerance can be condescending. It is a space of recognition. Of difference, yes—but a difference rooted in togetherness.

In a world where difference is so often seen as threat, this church is an architectural manifesto: it believes in the power of coexistence. And perhaps—just perhaps—peace between denominations does not begin with a council, but with a glance beyond the backrest of one’s own chair.

Because sometimes, new dogmas aren’t needed. Just a door. Or better yet: a wall that can be opened.

İki Sunak Arasında: Umut Mimarisi Olarak Ekümenizm

Katolikler ile Protestanlar arasındaki ayrılık – aynı Hristiyan kökenden gelen iki yüz – asla sadece günahların bağışlanması, ekmek-şarap anlayışı ya da endüljanslar hakkında doktrinsel bir tartışma olmamıştır. Bu ayrılık – her ayrılık gibi – psikolojik bir eylemdir. Sessiz bir güvensizliktir ve zamanla fiziksel yapılara dönüşmüştür: ayrı ibadethaneler, ayrı ritüeller, ayrı aileler.

Luther’in Roma’ya fırlattığı ayrılık taşı, yalnızca Vatikan’a saplanmakla kalmadı; sade insanların evlerine kadar yuvarlandı. Bir Katolik kızı bir Protestan delikanlıya âşık olduğunda titreyen yalnızca kalp değildi; aile içindeki barışın temeli de sarsılıyordu. Evlilik – birliğin sembolü – ayrılığın sahnesine dönüşüyordu. İki mezhep, tek bir yemin – ama hangi sunağın önünde?

Karlsruhe-Oberreut’taki Ekümenik Kilise yalnızca bir bina değildir. Düşüncenin taşa dönüşmüş halidir. Teolojik diller arasında kurulan anlamlı bir köprüdür. İçinde paradoksal bir fikir taşır: Birlik için ayrılık. Sırt sırta duran iki dua odası – birbirini görmeyen ama aynı kalp atışını paylaşan ikizler gibi. Ve aralarında: üçüncü bir mekân.

Bu mekân bir geçit değil; karşılaşmanın, kütüphanenin, girişin, diyaloğun yeridir. Katolik-Protestan bir evliliğin kimseyi inkâr etmeden – ne inancı ne ailesini – gerçekleşebileceği bir yerdir. Duvarlar açılır, sandalyeler döner. Teolojik olarak uzlaşmaz görünen şey, mimariyle anlaşılır hale gelir.

Burada mimarinin kendisi vaaz verir – kelimesiz ama etkisiz değil. Malzemeler öyle seçilmiştir ki sanki diplomasi inşa ediliyormuş gibi. Işık rastgele düşmez; bir işarettir. Her şey anlam yüklüdür, çünkü her şey umut taşır.

Umberto Eco’nun gülümseyerek söyleyebileceği gibi: Bu ibadethane bir metindir. Ve bu metin “Ya – ya” değil, “Hem – hem de” der. Bu bir hoşgörü sarayı değildir – çünkü hoşgörü çoğu zaman üstten bakar. Bu, tanımanın mekânıdır. Farklılığın – evet – ama kökleri ortaklıkta olan bir farklılığın mekânı.

Farklılığın çoğu zaman tehdit olarak algılandığı bir dünyada, bu kilise mimari bir manifestodur: bir arada var olma gücüne inanır. Ve belki – sadece belki – mezhepler arası barış bir konseyle değil, sadece bir sandalyenin arkasına bakmakla başlar.

Çünkü bazen yeni dogmalara ihtiyaç yoktur. Sadece bir kapıya. Ya da belki daha da iyisi: Açılabilen bir duvara.

THE POETRY OF CONCRETE

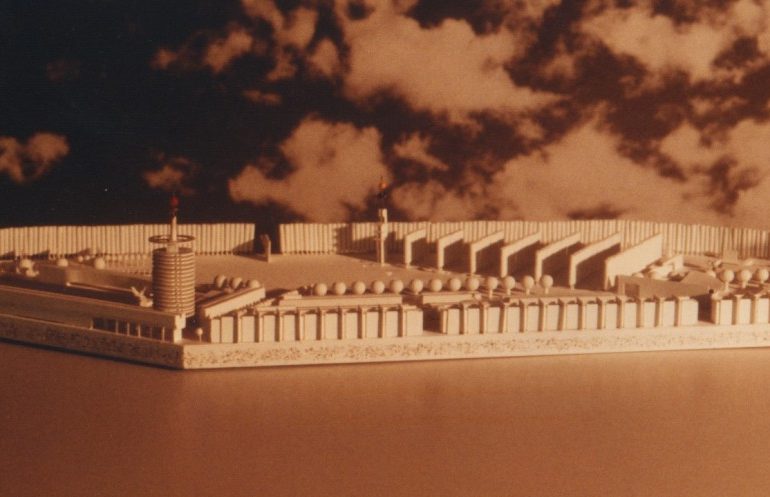

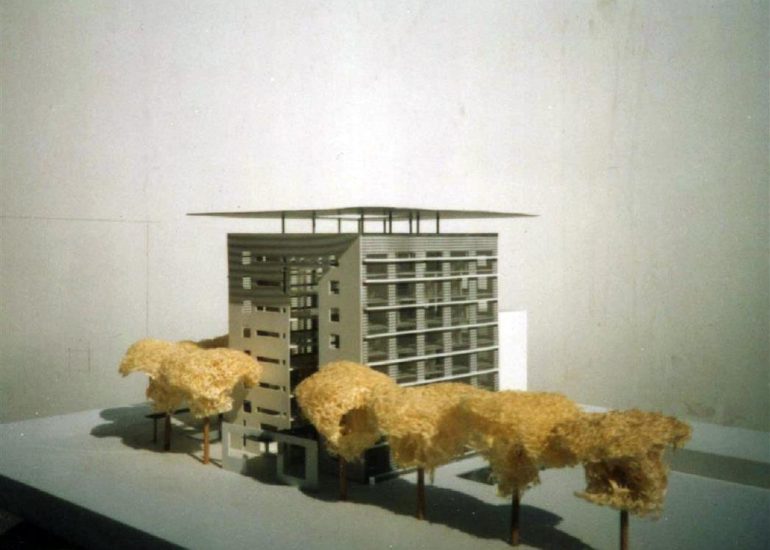

Cities grew, stone upon stone was laid. But some stones are more than just stones. They are the dreams built over centuries, the hopes molded with labor, the raw yet honest expressions of humanity. They are the towering masses of concrete—unpolished, unadorned, unapologetic. They are Brutalist structures.

Like giants standing tall, as if the sky itself had been torn open. To some, they are cold; to others, crude. But the eyes see what the heart is willing to accept. The bareness of concrete whispers that there is nothing left to hide. Walls stripped of ornamentation, free of pretense, standing in their true form. Tall, rigid, angular. Yet within them, a hidden warmth. Behind those solid facades, there is life, there is breath, there is humanity.

These concrete walls sing the song of labor. They reveal the truth to those who dare to look. —without embellishment, direct, sincere. Like the calloused hands of a worker—worn yet strong. Like a revolution—deep, striking, and filled with reality.

Man often competes with concrete, tries to shape it, tame it, bend it to his will. But Brutalist structures do not yield. They refuse to bow, refuse to charm. They rise as they are, just as a poet writes his verses without compromise. They are not the architecture of convention but of truth.

And perhaps that is why not everyone loves them. Because not everyone is ready to face the truth.

But truth is always there.

———————————

BETONUN ŞİİRİ

Şehirler büyüdü, taş üstüne taş kondu. Ama bazı taşlar var ki, onlar sadece taş değil. Onlar, insanların yüzyıllardır kurduğu düşlerin, emekle yoğrulmuş hayallerin, sert ama bir o kadar da dürüst ifadeleri. Onlar, ağır ağır yükselen beton kütleler; süslenmemiş, cilalanmamış, gizlenmemiş. Onlar brutalist yapılar.

Gök delinmiş gibi dimdik duran, derinlerde bir yerlerde kalbi atan devler… Kimine göre soğuk, kimine göre kaba. Ama bakan göz neyi görmek isterse, onu görür. Betonun çıplaklığı, saklanacak hiçbir şeyin kalmadığını fısıldar insana. Süsten, aldatmacadan, gereksiz ciladan arınmış, olduğu gibi duran duvarlar. Yüksek, sert, köşeli. Ama içinde bir sıcaklık gizli. Orada, o sert duvarların içinde insan var, nefes var, yaşam var.

Bu beton duvarlar, emeğin şarkısını söyler. Gözünü kaçırmadan bakabilene, gerçeği gösterir.Süslü kelimelerle değil, doğrudan, içten, dürüst. Tıpkı bir işçinin nasırlı elleri gibi; yıpranmış ama güçlü. Tıpkı bir devrim gibi; köklü, sarsıcı, ama hakikatle dolu.

İnsan, betonla yarışır bazen. Ona şekil vermek ister, onu ehlileştirmek, onu eğip bükmek ister. Ama brutalist yapılar buna izin vermez. Onlar kimseye boyun eğmez, kimseye şirin gözükmeye çalışmaz. Tıpkı bir şairin, dizelerini kaleminden olduğu gibi dökmesi gibi, brutalist yapılar da içlerinden geldiği gibi yükselir. Onlar, kalıpların değil, gerçeğin mimarisidir.

Ve belki de bu yüzden, herkes sevmez onları. Çünkü herkes gerçekle yüzleşmeye hazır değildir. Ama gerçek, her zaman oradadır.